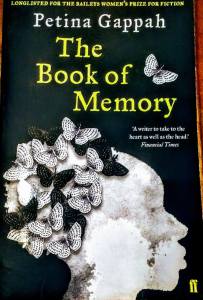

Author: Petina Gappah

Finished on: 12 June 2017

Where did I get this book: The huge Manchester Waterstones

This book tells the life story-so-far of Memory, a woman living on death row in Zimbabwe, sentenced for killing her wealthy white benefactor and adopted father.

I love a book where we know what the document is that we’re reading, and in Memory’s case she is writing in notebooks provided by her lawyer so she can tell a western journalist about her experiences. The hope is that is she can get enough attention for her case to ultimately be granted a pardon.

We start with Memory’s memories of being sold by her parents as a nine-year-old. But where we go from there is far from straightforward. This is one of the most incoherent, jumbled narratives I have ever read. It reminded me of a conversation with a drunk person. Or with my four-year-old son, who considers “Can I have a cheese sandwich, that fire engine has a very long ladder, two hundred pheasants, CAKE!” to be a cogent sentence.

For a while I found it frustrating. There is a lot of jumping back to replay the same events, and we didn’t seem to be getting very far. But, I suppose, so it is with memories. And as a meditation on how people remember the complex web of interconnected events that make up a life, both what is real and what is misunderstood, this book is something special. Gappah is particularly strong on how memories of events in childhood shape the rest of our lives, many of which are naturally misremembered fabrications, either because of a childish lack of understanding, or for self-preservation so that we create a life narrative we can cope with.

Then just as I was getting used to, and indeed enjoying, Memory’s leapfrogging-around-her-life narrative style, she stops it, and becomes all conventional. This really is a book of two halves (or rather, a book of three quarters and one quarter). The final quarter becomes all exposition and tying up ends neatly, occasionally bordering dangerously on the saccharine.

But there is so much to enjoy in this book we’ll forgive her the flirtation with cheesiness at the end.

Gappah is a lawyer, and her confidence navigating the legal intricacies of Memory and her prison-mates’ circumstances is clear. And the glimpses we get of the changing political landscape in Zimbabwe are beautifully done too; the insight is worn lightly.

My favourite thing of all about this book, though, is the belief in the redemptive power of reading that shines through the whole story. I am a sucker for a book about loving books, I really am. And Memory, and I deeply suspect Gappah herself – I don’t know if you can fake that passion – have an understanding that there is nothing better than the right book at the right time. Or indeed, any book at any time: the biggest heartbreak of prison life being the absence of reading matter. There are some genuinely affecting moments on the importance of reading in the life of a bookworm.

So, while it’s true that this book is sometimes undisciplined and inconsistent, it is also fascinating and ever so moving. It is unique. Yes, much like my four-year-old son.

Advertisements Share this: