Human suffering will remain insoluble as long as human beings exist. The only truly effective solution for suffering is that spoken of in [Peter] Zapffe’s “Last Messiah.” It may not be a welcome solution for a stopgap world, but it would forever put an end to suffering, should we ever care to do so. The pessimist’s credo, or one of them, is that nonexistence never hurt anyone and exsitence hurts everyone. Although our selves may be illusory creations of consciousness, our pain is nonetheless real. – Thomas Ligotti, The Conspiracy Against The Human Race: A Contrivance of Horror, 2010, p.75

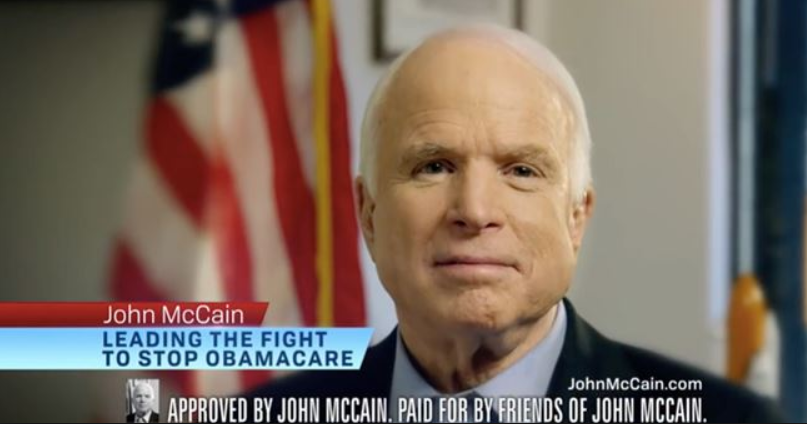

Author Thomas Ligotti

I think it no accident that two of the most influential western thinkers arrived at similar conclusions regarding the status of existence, even though they began with very different assumptions. I also think it no accident that these conclusions were first articulated in the aftermath of World War I. The Second World War may have surpassed it in terms of global destruction and body count, but the horror of trench warfare, both in Belgium/France and Russia, and the destruction of European Imperial dynasties was a cataclysm from which millions never recovered.

In Marburg, Germany, a young Martin Heidegger insisted that at the heart of existence is “The Not”. This “Not” is not just the negation of all affirmations. It is the negation of all negations as well. Human existence, Heidegger understood years before Freud proposed something similar, is “a being toward death.” Dasein, that untranslatable word that refers to each and every being that finds itself cast into the world unprepared and even unawares, finds itself an actor in a play already in progress, doing the best it can with the tools it is given. What drives Dasein, however is not some metaphysical force, or the appeal of virtue, or God or Satan or angels. At the heart of all existence is this “Not” that creates for all being a “being toward” death, the pursuit of our own negation that is, paradoxically, negated by this very same “Not”. In short, there is no wizard behind the curtain because there is no curtain, no behind. There is “Not”.

In the same decade, young Swiss pastor Karl Barth insisted that the triumphalism of much western Christian theology rested on a false sense of our relationship to God. Having returned to study the Christian Scriptures closely, Barth understood that at the heart of the Gospel message was a Divine “No” that brooked no argument, that lay waste to any and all human claims to righteousness, goodness, and the eventual progress toward the Kingdom on Earth. While Barth also said there is a Divine “Yes” that follows that “No”, he was at great pains through millions of words to strip Christian theology of any notion that everything we humans have built, up to and including the Christian Church and its theology, stands under the final, cataclysmic verdict, Nein. Left to our devices apart from the divine activity of the Triune God in the passion of Jesus Christ, human beings are and will always be bound for destruction.

In the 9 decades since these thoughts were first offered, thinkers great and small have wrestled with them. To no avail. Stripped of the pretenses with which we console ourselves – even our biological name, Homo Sapiens sapiens, is a joke we play on ourselves – we human beings are little more than pigs rooting in our own shit and muck, devouring whatever enters our mouths, our genetic programming pushing us to rut with anyone available in order to keep the species going, then living out our days watching our bodies decay from the inside out, the pain of our long dying never matched by any real pleasure or joy by which we convince ourselves that, contrary to these naked realities, “we” really “are”. Consciousness, in whatever way we understand this particular word – and there’s not even a guarantee that it refers to anything at all, particularly something that separates us from other species on Earth – is the result of blind accident, a mutation like our opposable thumbs and upright posture that may, at one time, have offered a marginal survival advantage but now, after millennia of misuse has long outstayed its welcome. Through consciousness, most people assume, we “are” human. Except, alas, all “consciousness” has done is left us aware that we have not been, and will not be again, and that what happens in between those twin darknesses has no meaning whatsoever.

In a nutshell, the above paragraph summarized much of the description of human existence offered by Ligotti in his interesting, thought-provoking work. Rooted in the work of little-known Norwegian thinker Peter Wessel Zapffe, embracing the pessimism of Schopenhauer, and offering as our only hope for relief from suffering the extinction of the human race, Ligotti’s is not so much a “pessimistic” philosophy as it is one of horror and despair. Which is no surprise, considering Ligotti’s main claim to fame is as a horror novelist. How better to present the horrible truth at the heart of existence than through the symbols and conventions of weird fiction?

Reading Ligotti, you realize fairly early on there will be no life-line thrown to escape the bleak, frightening presentation of existence as, in his own words including capitalizations, MALIGNANTLY USELESS. We are offered no solace in love, no comfort in courage, no respite in family or community. We human beings are not what we believe ourselves to be. Indeed, the very notion of a “self” is just one of the many ways through which we attempt to console ourselves that being alive is a moral good. Our sense of ourselves as a “self”, a unique, contained, integrated individual is nothing more than the creation of a neurotic mind desperate to shield the harsh reality from breaking in and destroying our minds completely (Freud understood as much, yet counseled that in this case the illness was preferable to the cure). Heidegger’s “Not”, Barth’s Nein, these extend even to our very selves. We are uncanny to ourselves, little more than animated puppets with nothing pulling our strings yet never fully free to “be” as we would wish to be. This book is much as the reality Ligotti describes – barren of reason, hope, and any soft, mitigating consolation to make it more palatable.

I found myself intrigued as I read, finding much to commend in Ligotti despite the atmosphere of despair that hangs over the book. In stripping existence of any illusion, we come face to face with the real horror we have all too often converted into smaller, manageable horrors. Ligotti does so without apology. This horror, that we as creatures have become, through the paradoxical working of natural selection, the negation of creation, is the kind of thing H. P. Lovecraft considered in his stories of beings with unpronounceable names and terrible designs upon us and our world: enough to drive us mad should we see it or hear it in its terrible reality. As a “contrivance of horror”, the kind of cosmic nihilism at the heart of Ligotti’s presentation surely is the most frightening of all: That our existence is nothing at all.

For all I would commend this book as an important corrective to the flood of bullshit too often presented to us in the guise of “motivational speaking” and “Christian literature”, it is important to note that, even though they may very well be the consoling lies of those desperate to shield us from the terrible truth of our existence, the fact is there are things that make life not at all MALIGNANTLY USELESS. Among these perhaps comforting lies is courage: that virtue that pushes human beings to live through all sorts of horrors and pain, big and small. Whether it’s the courage of the soldier who steps in front of a bullet or jumps on a grenade meant for others; the parents of a child born with incredible deficits who nevertheless strive to give that child a life of relative ease; those who work to make our collective lives more humane; these things are as real as the horrors from which they might shield us.

Along with courage is the sense, an intuition that may well be rooted in biological imperatives, that human life, in and for itself, is valuable. Not just our own lives, for which we may or may not care much at all, but the lives of others. Human beings are valuable simply because they exist. They are that rare thing, indeed: another like us deserving of our care, our assistance, conspirators in our desire to keep the darkness at bay. The preciousness of human life may well come from our understanding that nothing lies behind what is, including ourselves as conscious beings. In our desire for the care of others, we are not only protecting ourselves from the horrors of our consciousness of our own nonexistence; positively, we are affirming that human beings are and ought to be creatures subject to care and concern.

Finally, there is love, a word absent from Ligotti’s work. For Karl Barth, at least, it is Divine Love that negates the negation at the heart of creation. Indeed, the first negation is not at all part of the Divine plan but rather the result of human being believing it possible to stare into an abyss from which God sought to protect us. Pushed to consider life in all its variety, most people conclude that, in whatever shape it makes itself known, love sits even more deeply in existence than the terrible “Not” that is so horrible it is its own negation. In the faces of those who often crowd our lives with their presence, in the feeling of a child’s arms around the neck, in that most precious encounter between human beings, an encounter that brings with it a kind of mindless pleasure, we understand we are in the presence of a mystery far more deep than the simple realities of a world stripped of pretense.

Ligotti muses at one point on the fleeting nature of beauty and pleasure. Whether it’s the horrible pleasure that comes from the use of some narcotics, or the transcendent pleasure of sex, Ligotti and I agree on this: At its most supreme, pleasure is a fleeting moment that all too often pushes us to an eternal pursuit for it to happen again and again. For Ligotti, the reality of pleasure is given the lie as something valuable in and of itself precisely because it is so fleeting. For me, however, those moments of sublime pleasure, however they’re experienced, are testimony to the fact that the truly transcendent pleasures in this life – the sounds of a musical piece that bring goosebumps; a vista of sun and land that overwhelms our senses; that moment of human union that we shroud with mystery yet sometimes disparage as little more than the result of biological imperative – must needs be fleeting. Despite Ligotti’s claims, the horrible truth that may very well be the totality of our existence, can indeed be seen without madness ensuing. A moment or two longer of some fleeting pleasure that pushes outside the experience of that pleasure, however, we are quite sure will destroy us. A marvelous ending, to be sure, but an ending nevertheless.

In other words, we can live – perhaps not happily, certainly never easily – with the idea that we are not at all what we believe ourselves to be and that the nothingness that sits at the heart of Creation is the final truth. I’ve known many, including myself, who have stared long into that particular abyss and come away more or less psychically intact. That with which we cannot live, however, is the truth revealed in moments of rapture that there is a blinding, all-enveloping promise of love, an affirmation of existence as, far from MALIGNANTLY USELESS, but rather something sublime to be defended at all cost precisely because the negation of the “Not” at Creation’s core is a pleasure beyond our mortal abilities either to comprehend or sustain. These are no more “illusions” than are our intuitions that we hear a transcendent Nein to all our pretenses and neuroses that would deny that very same No. To claim otherwise isn’t so much pessimism or nihilism as it is a denial of the reality of all our experiences and intuitions, including those that lie at the heart of Ligotti’s desperate view of existence.

Advertisements Share this: