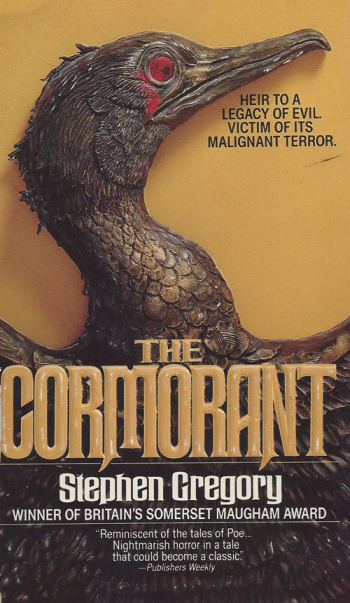

The Cormorant

Stephen Gregory | St. Martin’s Press | 1986 | 213 pages

A rumination on the nature of obsession, The Cormorant instills the specter of its titular bird–squawking, snapping its curved beak, or releasing sprays of liquid excrement—across nearly every page, building a malignant foreboding that culminates in inevitable tragedy.

“The cormorant was a lout, a glutton, an ignorant tyrant.”

The unnamed narrator inherits a cottage in the Welsh countryside from his bachelor uncle, who he recalls only meeting at family funerals, but with an unusual stipulation. In order to keep the cottage, he must care for his late uncle’s cormorant, a seabird that was rescued from a muddy death in the estuary of the River Ouse, and raised to fill the void of avuncular loneliness.

“Snaking its neck, it hissed a long malodorous hiss and brought up a pellet of half-digested matter which lay steaming in the weak sunshine.”

An unhappy teacher like his uncle, the narrator longs to escape his mundane existence in the suburbs of the English Midlands. Downplaying the role of caretaker to the cormorant, he and his wife, Ann, and their young son, Harry, accept the seemingly miraculous opportunity provided by the inheritance, and flee to the cottage in Wales to begin their new life. Their complacent attitude towards the cormorant is shattered immediately upon its arrival, their unlikely new ward exploding out of its box in a combative fit of hissing, spitting, and virulent shitting.

“It came from its box as ugly and as poisonous as a vampire bat.”

Relating to the bird as an agent of destruction against the normalcy of life and the hypocrisy of societal good behavior he left behind, the narrator slowly develops a relationship with the cormorant, whom he names Archie, eventually taking it out on fishing excursions. Ann does not share the growing affection towards Archie, fearing for the safety of Harry, who seems to exhibit a strange fascination of his own towards the seabird. And, of course, the family cat doesn’t stand a chance.

“The bird stalked around on its webbed feet, putting them down with a slap in the water and in its own many-coloured squirts of shit.”

The narrator’s obsession with Archie, whose presence informs the entire narrative, grows along with the palpable sense that all will not end well in the cozy Welsh cottage. Although arguably not an inherently evil creature, Archie drives a wedge in the family, the constant unease foreshadowing certain horror to come. Even the family’s behavior away from the bird creates discomfort, in particular a soapy, romantic encounter between husband and wife in the bathtub, with the infant son playing a squirm-inducing role. A Christmas-day dinner with neighbors becomes the perfect stage for everything to unravel, with the obligation to put on a polite face becoming increasingly difficult against the mounting terrors.

“Its jabbing bill came through, it hung for a second, scrabbling with its fleshy feet, it wings outstretched on the wire, like some gas-crazed soldier on a French battlefield.”

Not all the threads of the story are adequately explored, however. A shadowy figure seen observing from a distance and the inexplicable aroma of cigars in the cottage suggest a ghostly visit from the late uncle, but are not fully developed. His ghostly hand possibly helps the drunken narrator home from the pub, only to set up the fatal circumstances for the book’s conclusion.

“The bird came at me in to leaps, brandishing the heavy beak, punishing the night shadows with the power of its wing beats.”

Ultimately, the simultaneous empathy for Archie and the shocking nature of the finale, unexpected in its horror even though presaged, fuse to deliver a minor masterpiece of macabre terror.

Advertisements Share this: