History of corporal punishment and capital penalty would be much less rich without the Persians’ inventiveness. If one was to establish a podium celebrating the most creative persecutors of all time, the Persian Empire, which has peppered Antiquity with cruel, hellish tortures, would probably take first place (with medieval Inquisition right on its heels, closely followed by reality TV).

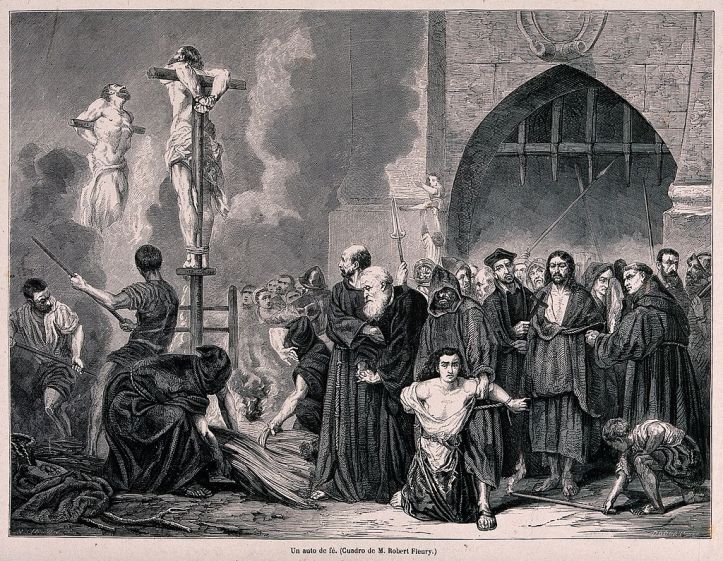

Spanish Inquisition introduced the ‘autodafé’ – an exotic name for being burnt at the stake. (Engraving: Bocort/H.D. Linton via Wikipedia, CC BY 4.0)

Spanish Inquisition introduced the ‘autodafé’ – an exotic name for being burnt at the stake. (Engraving: Bocort/H.D. Linton via Wikipedia, CC BY 4.0)

But there have been some punishments whose logical basis still escapes historians to this day. Let’s go back in time to land in Asia Minor, 5th century B.C. – at a time when Persians ruled about half the developed world.

From 492 to 490 B.C., the First Persian Invasion has left a trace within the Greeks’ minds. Entrenching themselves in their city states, threatened by the Persian Immortals, they eventually managed to get out of trouble thanks to a hairy messenger and the first-ever marathon runner. Surely, history had been played on a razor’s edge, but Persians were heading back to their homeland while Spartans, Athenians and other Greek victors juggled with amphorae and danced sirtaki before it was cool. (Thanks in advance for not taking the lack of historical rigor of that last sentence into account.)

However that peaceful period was soon to come to an end. Persian King Xerxes I had succeeded to his father Darius after his death, and planned on invading Greece again to avenge him. The new king thus spent a few years secluded in his palace, preparing the assault, recruiting soldiers and handling the logistics. Finally, in 480 B.C., his cosmopolitan army journeyed to the Dardanelles (or Hellespont) Strait, separating Asia from Europe. From Abydos, where the strait was only 1.2 kilometers (about 1,300 yards) wide, Xerxes planned on invading Greece. All he needed then was to cross the sea.

On that map, we can spot Abydos, from which Xerxes aimed at reaching Europe. We can also spot Epidamnus, which is not related to that story, but proves you have good eyesight. (Map credit: Bibi Saint-Pol via Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0)

On that map, we can spot Abydos, from which Xerxes aimed at reaching Europe. We can also spot Epidamnus, which is not related to that story, but proves you have good eyesight. (Map credit: Bibi Saint-Pol via Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Xerxes thus ordered his soldiers to start building a pontoon bridge so as to link both banks. It took some 674 ships, tied together with papyrus and flax ropes, to bridge the gap between the Asian and European continents. But as Xerxes and his army were about to cross it, a storm ravaged the pontoon bridge and all his men’s work. All had to be done again, from scratch!

Pontoon or floating bridges are an essential warfare tool, depicted here at use of the US Army during WW2. Building a Pontoon Bridge for Dummies, Step 1: Check the weather forecast.

Pontoon or floating bridges are an essential warfare tool, depicted here at use of the US Army during WW2. Building a Pontoon Bridge for Dummies, Step 1: Check the weather forecast.

Needless to say that the Persian King was far from happy; he immediately got the architects considered responsible for the mess executed. (Historians keep wondering whether he threw a stone at the clouds shouting “Damn you, condensed atmospheric water vapor!” or not.) Still, according to Herodotus, this was not the strangest punishment ever ordered during the Greco-Persian conflict…

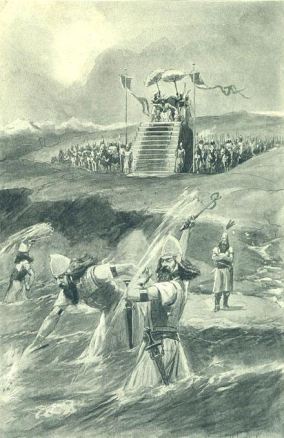

Indeed, Xerxes also meant to chastise the waters which took the bridge away. His soldiers were to injure the sea and whip it three hundred times, while handcuffs were also dropped into the strait so as to symbolize its submission to Xerxes’ authority.

“My son [Xerxes], with all the fiery pride of youth, hath quickened their arrival, while he hoped to bind the sacred Hellespont, to hold the raging Bosphorus, like a slave, in chains, and dared the advent’rous passage, bridging firm with links of solid iron his wondrous way.” – Aeschylus, The Persians, circa. 472 B.C.

Persian soldiers whipping the sea, with Xerxes watching in the background.

Persian soldiers whipping the sea, with Xerxes watching in the background.

In the end it took seven days and as many nights for Persians to cross the Dardanelles Strait and reach Europe. Yet their problems did not end there: Xerxes weathered brave resistance from the Greek side, especially at the Battle of Thermopylae where 300 Spartans (spearheaded by their King Leonidas) held the Persian army back for days. Despite his delayed victory, Xerxes suffered heavy losses while attempting to subdue the Southern provinces. Eventually the Greek fleet drove away the Persians back to their home continent.

Herodotus also mentioned that powerful storms contributed to the enemy’s rout, as they decimated the retreating Persian fleet, definitely burying Xerxes’ hopes for conquest of the Greek peninsula.

As regards fleeing Persian foot soldiers, lots of them stopped dead on their tracks when they reached the European bank of the Hellespont Strait, as the pontoon bridge had been torn apart by waves… again.

Sources:

- Didier Chirat, La Petite Histoire… du Monde : 20 moments méconnus mais décisifs de l’histoire du monde (2016), éd. Librio, p. 11

- http://www.spiegel.de/international/zeitgeist/the-worst-ways-to-die-torture-practices-of-the-ancient-world-a-625172.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Persian_invasion_of_Greece

- https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/D%C3%A9troit_des_Dardanelles#Histoire

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xerxes%27_Pontoon_Bridges