Have you ever wondered what North America looked like sixty-five million years ago? Or how life on the continent recovered after the cataclysmic Chicxulub struck the landmass? These are the questions Tim Flannery – a prominent, Australian ecologist and environmentalist – seeks to answer in his book The Eternal Frontier (first published in 2001).

Flannery’s narrative begins when the asteroid Chicxulub collides with the Earth. Its destructive power annihilates the dinosaurs and virtually wipes the North American continental slate clean. From here, he beings to introduce a range of cast and characters. First came the plants, the pioneers that colonised the continent. Then, over time came the giant sloths, direwolves, one tonne lions, mammoths, bisons and mastodons. While the North American continent takes centre-stage, Eurasia, South America, Europe and even Australia played a supporting role in the evolution of its biodiversity. We learn for example, that many species of birds that are currently found in North America are of South American origin, while many of its mammals originated in Eurasia.

After charting the ebb and flow of life on the North American continent, Flannery turns his attention to the arrival of the first nations people into North America. Their arrival (some fourteen thousand years ago), is the start of the ‘blitzkrieg extinction’ period – one where the large megafauna began to disappear due to hunting and the changes in land-use and vegetation structure. A similar phenomena took place in Australia, where the megafauna disappearance coincides with the arrival of the Aboriginal people. The North American ecological balance finally tips with the arrival of French, Spanish and European settlers. Today, mass consumerism has become “an economic machine that is eating the life of the continent” (Benjamin Franklin in The Eternal Frontier, pg. 351).

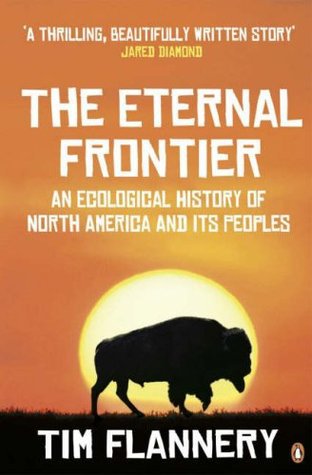

The Eternal Frontier by Tim Flannery

The Eternal Frontier by Tim Flannery

With his deeply imaginative writing coupled with forensic scientific examination, Flannery weaves a compelling and dramatic story. He punctuates the reader’s journey into this fascinating and deadly landscape with open ended questions, analyses competing theories and uses excerpts from journals and letters. He also provides a short summary of key ideas and developments at the end of each chapter help to keep readers on track. By the end of the book, readers will come to look at North America in a new light.

While Flannery takes his readers on a grand adventure, I think he is over ambitious in seeking to cover the ecological and evolutionary history of a continent that spans over sixty-five million years. I think that Flannery should have kept the focus on a specific time frame or chosen a particular event such as a conclusion to the story. This would have paved the way for a second volume, giving him more scope for a detailed examination. The continued introduction of new species of plants and animals also makes it confusing at times for the reader to keep up with the narrative and here, I think a collection of images or artist impressions would have been useful.

While the book is interesting, informative and imaginative, I think that some North American readers will not enjoy it as much, particularly, when Flannery forays into the impacts of humans on ecology and biodiversity. I think that his broad brush-strokes, perhaps justifiably, end up painting many of the human colonists of North America in a bad light.

Overall though, Flannery’s The Eternal Frontier is a worthy addition for anyone interested in the evolutionary history of the North American continent – and, indeed, the planet.

Advertisements Share this: