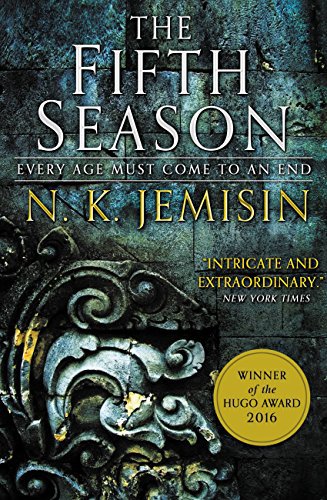

What it’s about: The world is destroyed. Amidst the ruins, a woman, cursed from birth with abilities that make her a monster in the eyes of humanity, seeks revenge against her husband, who has murdered their child.

Notes:

- The Fifth Season merges epic, geologic-scale fantasy with intimate portraits of the people who live in a world that is quite unique in the genre. The world of The Fifth Season is an Earth, which, having lost its Moon long ago, is wracked by intense geologic activity; once every few centuries, a massive volcanic eruption or some other natural disaster gives rise to protracted periods of catastrophic climate change, called Fifth Seasons. The civilisation of the day, a massive empire spread out across the single continent, has developed strict codes of oral and written history that dictate the precise actions that people must take in the event of a Season, in order that their communities can survive until the Season ends.

- Within this context, there are orogenes, people born with the power to control the flow of energy in a system. Since the power is so innate to them, if untrained, they lose control and are liable to kill entire towns. As a result, they are feared and hated, and only sanctioned as part of an organisation called the Fulcrum, where they serve humankind by using their powers to stabilise the geologically hyperactive Earth, to minimize the incidence of Seasons.

- This conceit sets up a lot of opportunities for the book to act as a commentary on race and gender relations. Certainly, The Fifth Season is a novel for the disadvantaged, one that eschews the stereotypical male white power fantasies so endemic to the genre’s canon and replaces them with deeply disadvantaged characters whose circumstances were theirs from birth.

- However, the characters that populate the book are anything but passively resigned to their fate. The book is subdivided into three points of view in three different times, of orogene girls and women at different stages of their lives, trying to survive and make a life for themselves, in a broken world. This narrative triptych proceeds at parallel for most of the book, until it ties together in a not entirely unexpected, but very satisfying, fashion.

- The book was feted almost hyperbolically upon release, winning a Hugo award. Certainly, it has its merits and a calibre of worldbuilding up there with Brandon Sanderson in its creativity. Its prose is rich with a kind of wry irony, a tone that almost knowingly knows what tropes the reader is expecting and either pre-empts or subverts them. The main character, Essun, for example, is originally portrayed as a broken middle-aged woman, shattered by the death of her son at the hands of her suddenly abusive husband. But as the plot progresses, Essun’s inner monologue begins to reveal a much more complex and prickly history, and Jemisin winks at the reader by just making Essun wryly self-aware of the disparity between who she is and who she appears to be.

- A final point is that The Fifth Season has that spark in fantasy that always hooks me into it – that intimation, or suggestion, of deep history that suggests that the present world is the way it is because of mysterious events in the deep past, as evidenced by the various forgotten artifacts and ruins lying around, from a more advanced, hubristic time. And I like that the Earth is portrayed as a character, or at least an active agency in the book, but not your typical Gaia-like benevolence, but instead, as a vengeful, almost evil entity, evincing the exclamation, “Evil Earth!” from the lips of any of the denizens of the Earth. A reminder to us, in the real world, that the Earth can thrive perfectly well without us, and can – and will – kill us in a myriad of horrific ways, if we’re careless about exploiting it.

I give this book: 4.5/5 obelisks

Advertisements Share this: