This review first appeared in Crux, the magazine of the Astronomical Society of Victoria.

Amazing things happened at the Harvard Observatory around the turn of the twentieth century. Draper provided funding for photography of stellar spectra, while Bruce gave $50,000 towards a new 24-inch astrophotographic telescope. Pickering found the first spectroscopic binary, and Maury found the second; Fleming classified stellar spectra and discovered novae. Cannon worked on variable stars and explored the relationship between spectral type and magnitude; Leavitt also worked on variables and proposed the period-luminosity relation. Ames and Payne were Harvard’s first graduate students in astronomy.

Amazing things happened at the Harvard Observatory around the turn of the twentieth century. Draper provided funding for photography of stellar spectra, while Bruce gave $50,000 towards a new 24-inch astrophotographic telescope. Pickering found the first spectroscopic binary, and Maury found the second; Fleming classified stellar spectra and discovered novae. Cannon worked on variable stars and explored the relationship between spectral type and magnitude; Leavitt also worked on variables and proposed the period-luminosity relation. Ames and Payne were Harvard’s first graduate students in astronomy.

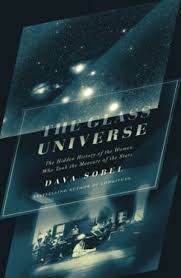

Anna Draper, that is. Catherine Bruce. Edward Pickering and Antonia Maury. Williamina Fleming. Annie Cannon and Henrietta Leavitt. Adelaide Ames and Cecelia Payne. As Dava Sobel makes beautifully clear in The Glass Universe, women were fundamental to the astronomical work and discoveries at Harvard Observatory in its early years. This is a book in love with astronomy and its history that wants to ensure everyone who contributed—not just the now-big names like Hubble—is recognised.

Sobel points out three groups of women who contributed to astronomy. She opens her book by demonstrating how women contributed financially to astronomical work. Anna Draper provided money and telescopes so that stellar spectra could be investigated at Harvard, and endowed the Henry Draper Medal. This was done in honour of her late husband, but also reflected her own interests: she had observed with Henry, and helped with the photography; part of their honeymoon involved shopping for a glass disk for a 28-inch telescope, which the pair then ground and polished over years to transform into a mirror. At 73, Catherine Bruce’s vague interest in the stars was encouraged by Edward Pickering and by her death in 1900 her gifts totalled $175,000 (over $4 million today). Other women endowed telescopes, awards, and scholarships.

The second group, appropriately taking up most of the book, are the individual researchers at the Observatory. Most of them started as computers: examining glass plates, calculating visible magnitudes, cataloguing spectra. Some of the women worked on this for decades. Some undertook further work as their curiosity was sparked by the spectra they investigated, or the magnitudes they calculated, or they noticed interesting relationships between period and luminosity. These women published papers, and contributed to the papers of other astronomers, especially Pickering and Harlow; some of them were awarded annual medals, although not many; some were honorary membership to societies such as the Royal Astronomical Society, while Cannon was the treasurer of the American Astronomical Society. The work these women undertook was thanks in no small part to the unusual willingness of Edward Pickering and Harlow Shapley (yes, that Shapley), directors at the Harvard Observatory between 1877 and 1952 (Solon Bailey had two years as interim director), to not only work with women but encourage their independent work and acknowledge them in publication. Their work is therefore also acknowledged and discussed, since it would be impossible to separate it from that of the computers in particular.

The third group of women consists of the wives and other family members of acknowledged astronomers. Solon Bailey’s wife, Ruth, contributed to his observatons for the Harvard station in Peru, while Pickering’s and Shapley’s wives played crucial roles at the Observatory in making the whole place work. The third director’s daughter, Anna, became a computer. They are the least well served by the book; it is presumably difficult to uncover contributions if they weren’t acknowledged at the time.

Dava Sobel has not only written a compelling history of Harvard Observatory, and not only conducted a remarkable survey of the contribution of women to astronomy, but has also written an intensely readable book. There’s some wonderful scientific discussions included, about Cepheid variables and their importance to figuring out the size of the universe and the like—but these do not dominate. If you are looking for a book about the history of astrophysics, this is not it and does not want to be it. No understanding of astrophysics is required to read it. Rather, this is a history of the people involved; it has a little about their relationships with one another, but it’s mostly about the work; it sounds like most of them put their work first anyway, so that’s appropriate. It demonstrates just how much computing power was required a century ago to understand the heavens—when that computing power could be jokingly measured in “girl hours”, and sometimes “kilo-girl hours”. The women who worked at the Harvard Observatory were a crucial part of the astronomical community.

Share this:- More