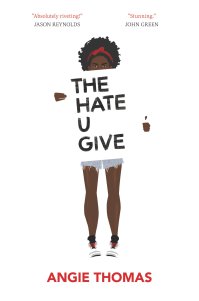

Angie Thomas’s young-adult novel, The Hate U Give, is one of the best books I’ve read in years. I truly could not put it down, and the only hate I have to give this book is the fact that it ended! I wasn’t ready to close the cover on Starr and her family and friends, who felt like they’d pulled me into their inner circle, letting me be a part of their lives through this compelling, intense, authentic, sad, and also heart-warming story.

Angie Thomas’s young-adult novel, The Hate U Give, is one of the best books I’ve read in years. I truly could not put it down, and the only hate I have to give this book is the fact that it ended! I wasn’t ready to close the cover on Starr and her family and friends, who felt like they’d pulled me into their inner circle, letting me be a part of their lives through this compelling, intense, authentic, sad, and also heart-warming story.

There is much to say about this book that features 16-year old Starr Carter, who is the sole witness to the fatal shooting of her childhood best friend, Khalil. Since the novel’s release in 2017 much has already been said. It’s been at the top of the New York Times best-seller list for 40-some weeks now. The film is forthcoming, complete with a stand-out cast. The Hate U Give was a finalist for both the 2017 National Book Award in Young People’s Literature and the Kirkus Prize, as well as listed on TIME’s Top 10 Young Adult & Children’s Books of 2017. Early reviews, a large number of which were starred, called it a classic and a book everyone should read.

The Hate U Give (Balzer & Bray, 2017) is a powerful coming-of-age story that honestly, powerfully, and fairly speaks to police brutality, the modern-day civil rights movement, racial stereotypes, finding one’s voice, interracial relationships, living authentically, and systemic racism.

Since the focus of reviews on this blog is to discuss how books pertain to the Neufeld paradigm, I will touch on one aspect of The Hate U Give that I haven’t seen mentioned in many of the reviews, and that is the portrayal of Starr’s village of attachment. It’s largely Starr’s wide circle of caring adults in her family and community, I believe, that create in the story such a beautiful tone of hope and love, even in the midst of some very dire situations. While Starr’s mostly black urban neighborhood of Garden Heights is painted as poor and gang-ridden, Thomas portrays Starr’s community as rich in heart, abundant with people who care, nurture, and unconditionally love their young.

Child developmental psychologist Dr. Gordon Neufeld regularly speaks of the importance of caring adults in a child’s life – people to treat our children’s hearts tenderly when peers, and the world in general, can be so wounding. “In today’s society, attachment voids abound,” Dr. Neufeld writes in his best-selling book Hold On to Your Kids. “Children often lack close relationships with older generations – the people who, for much of human history, were often better able than parents themselves to offer the unconditional loving acceptance that is the bedrock of emotional security.”

Not so in Starr’s world, in that regard. No matter the hard circumstances and alarm she’s faced with – even when she is physically in danger because of the color of her skin – it’s as if her soft heart is bubble-wrapped in protection because of the support she receives from so many caring adults in her attachment village.

First, there’s Mr. Reuben, owner of the BBQ shop who “remembers everybody’s names, somehow,” and genuinely connects with, and cares about, the youth in his community who frequent his restaurant. Here’s a lovely snippet from a scene after Mr. Reuben asks Starr and her friend Kenya how school’s going and whether they’re staying out of trouble:

“’How ‘bout some pound cake on the house then? Reward for good behavior.’

We say yeah and thank him. But see, Mr. Reuben could know about Kenya’s fight and would offer her pound cake regardless. He’s nice like that.”

Mr. Reuben intuitively seems to know that “the way to the heart is through one’s stomach,” isn’t just an old adage. The provision of food to help foster attachment has been proven both culturally and scientifically. (He’s not the only one in the community who knows this, either. In response to Khalil’s death, the whole neighborhood turned up with food. “‘That’s the Garden for you,’ Momma says. ‘If folks can’t do anything else, they’ll cook.’”)

There’s also Ms. Rosalie, Khalil’s grandmother, who Starr describes as “an African queen.” She gives what Starr describes as “the most heartfelt hug I’ve ever gotten from somebody who isn’t related to me,” and listens to Starr’s hand while holding it. “It’s like my hand is telling her a story, and she’s responding.” What a gift for Starr to feel significant and to matter, and to feel this kind of emotional intimacy and invitation to be known – all deeper levels of attaching – from someone who clearly treats Starr’s heart with care.

When there’s rioting in the neighborhood, Ms. Jones from down the street calls Starr’s mother to check in. Mr. Charles next door offers his generator if needed. Mr. Lewis, the barber whose shop is beside Starr’s family’s grocery store, may be cranky but underneath his crusty façade he’s supportive and turns out to be a strong hero in a time of crisis. Other secondary characters who wrap Starr up in a blanket of cross-generational love and support include her attorney, Ms. Ofrah, and Mr. Reuben’s son, Tim.

Dr. Neufeld often assures parents, educators, and helping professionals that children really only need one caring adult in their lives to make a difference. Sometimes the child might not have a caring parent at home (this is seen, sadly, in the lives of some of the other characters in The Hate U Give). But even one teacher, neighbor, grandparent, or other adult can be the person for the child to attach deeply to. In her community, Starr has several such adults she’s given her heart to … and I haven’t even gotten to the integral adults from her family yet.

Uncle Carlos is one such familial light to Starr. While Starr’s father was in prison for three years, Uncle Carlos became a surrogate father to Starr. To Starr’s delight and comfort, Uncle Carlos has a routine of two kisses on the top of his niece’s head. “I snuggle closer to Uncle Carlos and hope it says everything I can’t,” she describes. He’s the adult Starr calls when in distress at school, well aware she’s faking “feminine problems,” but there for her all the same – and while supporting her, pointing her back to her mother or father – as all good members of the attachment village do.

It’s also Uncle Carlos, a police officer, who helps keep the perspective that not all cops are bad. When he’s put on leave due to an incident where he physically stands up for his niece and Starr worries about his job, he says, “‘But I love you more. You’re the one reason I even became a cop, baby girl. Because I love you and all those folks in the neighborhood.’”

Uncle Carlos’s actions speak as loud as his words – not only in the shared care of Starr, but in his willingness to shelter a young man, DeVante, from Garden Heights as he tries to flee the King Lords gang. By the end, Uncle Carlos treats DeVante like a son, which is evident in his reprimand: “Of course I’m mad. I’m actually pissed. But I’m happier that you’re safe.”

For DeVante, Uncle Carlos may well be the one and only adult who makes a difference in his life (and that difference is visible and remarkable later in the story, too). Starr, though, is further blessed with two amazing parents, who tell her repeatedly how they’ve “got your back.”

Starr’s dad, Big Mav, may be an ex-gangster who’s done time, but he’s a stand-up father – loving, devoted, protective. That’s one of the themes that I especially relish throughout this novel: behaviors don’t make the person – whether it’s Starr’s dad, Khalil, DeVante, or any of the other characters. Just as in life, people aren’t pigeonholed as either good or bad, black or white – they’re complex, multi-faceted people, and when you look underneath their behavior, or their skin color, all you can see are their beautiful hearts. Big Mav has a big one, and it has certainly won over Starr’s heart, as a result.

Throughout, Big Mav is shown as strong, caring, and in-the-lead. His upper arm is tattooed with Starr’s baby picture and these words underneath: “Something to live for, something to die for.” Mav reminds Starr, “I’ll do whatever I gotta do to protect you.”

He echoes this message to his son, Seven. When Seven considers passing an opportunity at college to stay in Garden Heights and look after his sisters (whose abusive step-father heads the King Lords gang), Mav tells him: “Look, you not responsible for your sisters … but I’m responsible for you. And I ain’t letting you pass up opportunities so you can do what two grown-ass people supposed to do.”

It’s because of her dad’s alpha-caring that Starr (and Seven, too) finds rest, which you can feel in her descriptions:

- “I can tell it’s Daddy who’s rubbing my back without him even saying anything.”

- “Daddy pulls me into a hug … I could stay like this all day – it’s one of the few places where [Officer] One-Fifteen doesn’t exist and where I can forget about talking to detectives.”

- “Daddy being home means Momma won’t sit up all night, Sekani won’t flinch all the time, and Seven won’t have to be the man of the house. I’ll sleep better too.”

- “The crying, the puking don’t mean anything anymore. My daddy’s got me.”

Similarly, Starr’s mom gives her daughter the same kind of unconditional, I’ve-got-your-back-support that feels to Starr “as good as any hug I’ve ever gotten.”

Her mom is also particularly savvy at honoring Starr’s emotions and making room for them:

“You’re grieving, okay? … Grieve Khalil all you want. Miss him, allow yourself to miss what could’ve been, let your feelings get out of whack. But like I told you, don’t stop living. All right?”

In another scene, when Starr’s frustration is ready to come pouring out, her mom coaxes her while rubbing Starr’s back: “Let it out, Munch … Let it out.” And in so doing, she helps her daughter shed some hefty emotion. Starr says, “I pull my polo over my mouth and scream until there aren’t any screams left in me.” After the emotion has been released, Starr’s mom says, “You feel better?” and then, “We’ll get through this. I promise,” ultimately helping pave the way for Starr’s tears to flow and adaptation to take place.

Starr’s mom also offers smart counsel on friendships – seasoned with practical, simple advice to write down a list of the good stuff and bad stuff. She also has nothing but wisdom to impart to Starr when it comes to bravery, while also revealing to Starr how well she knows her daughter:

“I’m proud of you, baby. You are so brave.”

That word. I hate it. “No, I’m not.”

“Yeah, you are.” She pulls back and pushes a strand of hair from my face. I can’t explain the look in her eyes, but it knows me better than I know myself. It wraps me up and warms me from the inside out.

“Brave doesn’t mean you’re not scared, Starr,” she says. “It means you go on even though you’re scared. And you’re doing that.”

I am so thankful that The Hate U Give steps away from the unspoken rule to “get the parents out of the way to tell the story” that so many children’s authors – especially authors of young-adult literature – adhere to. That’s just not always realistic, nor is a peer-to-peer culture what’s needed for young adults to successfully launch and flourish. That doesn’t mean it’s not Starr’s story, or that she doesn’t have friends – but that family, and the hierarchy found within the full attachment village – is integral to her life and thus to her coming-of-age story.

“It’s strange, dysfunctional-as-hell family,” says Starr as she describes her community in Garden Heights, “but it’s still a family. More than I realized until recently.”

That “dysfunctional” family keeps Starr’s heart from hardening up in spite of systemic racism, profound grief, and unjust circumstances … and keeps the reader’s heart open to hope, too – for a better, hate-free future for us all.

Advertisements Share this: