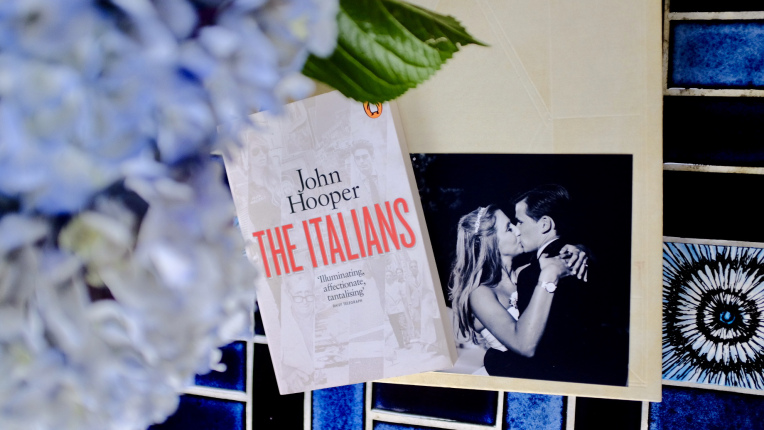

“The use of symbols and metaphors; the endless interplay between illusion and reality; the difficulty of getting at a commonly accepted truth: these are all the things that have made Italy both frustrating and endlessly intriguing – not least because they raise the tantalizing question of why a people who spend so much of their time peering behind masks and facades should nevertheless be so concerned with appearances; with what they see on the surface.” John Hooper, The Italians (2014)

I love books by journalists. They tend to be easy to read, conversational, and well-informed. Sure, maybe they don’t make me feel things like a memoir or in-depth biography, but they are incredibly entertaining, and my (nonfiction) version of a beachside read.

Last year, this weekend, I got married in Italy, then set off on a little Italian road-trip with my brand-new, just-out-of-the-box husband. We spent a week exploring, eating, and, of course, reading. I brought with me from London two books purchased at Daunt Books in Marylebone: Elena Ferrante’s The Story of a Lost Child (which is fiction so I won’t review here, sorry!) and John Hooper’s The Italians.

John Hooper was the Italian correspondent for The Guardian and The Economist for a little less than ten years, and after writing two books about Spain, he decided to tackle the Bela Paese.

The Italians is quirky and conversational. Hooper doesn’t begin with the Roman Empire and work forward to the present day. Instead, he weaves the country’s history around themes and characters essential to modern Italian national identity, which he also argues is a continuously developing concept.

The writing is clear and concise, like one would expect a professional journalist, and extremely interesting for someone new to Italian history and modern politics. It was full of antidotes like the story of Mussolini’s corpse hanging upside-down at an Esso gas station, Berlusconi making money in college by selling his essays to other students, and the Slow Food Movement starting as a reaction to the opening of a McDonald’s near the Spanish Steps in Rome.

Hooper also asks a bigger question – will Italy ever be truly unified? Invaded and under siege for most of its history, Hooper argues that borders of Italy have always been changeable, and the Italian identity is flexible in the same way. He discusses the word verità in Italian, which can be translated as ‘truth,’ but also as ‘version’. This double meaning, Hooper explains, is the perfect example of Italian’s relationship with the truth – there are many truths, many identities, many boundaries. The book utilizes Italian words as being symbolic for cultural ideas in Italian society.

Another example is the idea of furbo and fesso. The latter translates as crafty, sly, or cunning, maybe like a fox. Hooper is careful not to characterize Italian culture as completely furbo as it can only exist if it has a fesso to prey on (the version of a good person, loyal, moral, maybe like a dog). Hooper claims Italian history could be viewed as a long struggle between the furbo and the fesso of the county, and he says that with power changing hands so often in Italy, “principles, ideals, and commitment have proved dangerous.”

Although I enjoyed reading the funny historical anecdotes the most, the analysis of the words and how they play out in Italian culture is what I will remember most about this book.

I would suggest reading The Italians in Italy if you can, mainly because if you’re not already in there, it will make you want to hop on the next plane to Rome! Bravo!

If you liked this post, be sure to follow me on Instagram or Facebook for more updates and fun reads!

Share this: