In 2004, a student of Carnegie Mellon University named Neil Druckmann participated in a group project. At the time, he was pursuing a Master’s degree in Entertainment Technology, and one of his professors happened to be friends with George Romero, the man who directed Night of the Living Dead. This 1968 classic is widely considered to be ground zero for the zombie apocalypse genre. For this assignment, Mr. Romero compelled the students to pitch an idea for a video game. Mr. Druckmann’s idea merged the three works which left an indelible impact on him as a creator. It would feature gameplay akin to Ico, star a protagonist with a personality comparable to John Hartigan from Sin City, and the story was to be set in the world of Night of the Living Dead. The game’s concept centered on a cop would protect a young girl in a ravaged land filled to the brim with mindless, flesh-eating monsters. However, the cop had a heart condition that would act up every now and again, prompting players to take control of the girl in these situations, thus reserving the roles of the protector and the protected. In the end, Mr. Romero chose another project.

Later that year, Mr. Druckmann met Jason Rubin, the co-founder of a game company named Naughty Dog. Mr. Rubin’s company had made their impact on the medium on Sony’s PlayStation platform with their Crash Bandicoot series of 3D platforming games. It was a success that would continue into the following console generation with Jak & Daxter. After “bugging” Mr. Rubin enough, the co-founder handed the enthusiastic college student a business card. Shortly thereafter, Mr. Druckmann joined Naughty Dog as an intern before being promoted to full-time employee as a gameplay programmer mere months afterwards.

When his tenure at Naughty Dog began, Mr. Druckmann began to revisit his rejected game concept, thinking to himself, “What’s another way I can explore these characters?” The answer to this quandary came in the form of a comic book named The Turning. It was to be about a criminal who found himself tasked with escorting a young girl across a dangerous land. The roles would be reversed in the end when he is captured by erstwhile criminal partners and the girl saves his life. He intended to write and draw the comic itself. When he completed the script for a six-issue story arc, he submitted it to an independent comic book publisher. Unfortunately, much like George Romero, the publisher rejected the idea – Mr. Druckmann being told, “I like it, but I don’t love it.”

Meanwhile, as Naughty Dog was in the middle of developing Jak 3 and Jak X: Combat Racing, Mr. Druckmann asked co-president Evan Wells about joining the design team. Although Mr. Wells was hesitant about the idea, he allowed Mr. Druckmann a chance under the stipulation that he completed his design work after hours. Once Jak X: Combat Racing saw its release, Mr. Wells was convinced by his subordinate’s skill and put him in charge of design for their next project: Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune. This game and its sequel were commercial and critical successes, and Mr. Druckmann soon found himself as one of the lead developers for the series’ third installment.

As he worked on the design for the first two Uncharted installments, Neil Druckmann would often have dinner with co-worker Bruce Straley to discuss ideas about what they should do next. This time, his proposed story followed a man accompanied by a mute girl with whom every point of interaction was executed via game mechanics. During these sessions, they became intrigued with Cordyceps, a fungus that infects insects by taking control of their motor functions and forcing them to cultivate more of itself. This game was to be set in a world in which the Cordyceps began to infect humans, but only women fell victim to it. The girl was the only female immune to the fungus, and the hero had to transport her to a laboratory so a cure may be synthesized. The concept was vetoed when the company’s female employees voiced concerns about a game in which men had to band together against women who became ugly, irrational, and powerful. Not helping matters was its proposed title: Mankind. By Mr. Druckmann’s own admission, “The reason it failed is because it was a misogynistic idea.”

Undeterred by these numerous setbacks, he began to refine his idea, and in 2010, he and Mr. Straley felt it was ready to be pitched. However, it was rejected yet again when the higher-ups felt his new concept failed to mesh with his characters’ arcs. After weeding out the last remaining issues, Mr. Druckmann’s dream project was finally greenlit, being formally announced to the world in 2011. As Naughty Dog received innumerable awards and a large, dedicated fanbase with their trilogy of Uncharted games, this new title, dubbed The Last of Us, became one of the most hotly anticipated titles of its time. At long last, the medium would have a title to show the world that video games had grown up and were every bit as worthy of being considered legitimate artistic cornerstones alongside film, music, and literature. This heavily promoted game was released in 2013, and saying that it received unanimous critical acclaim would be a gross understatement. Critics felt it was one of the medium’s greatest artistic achievements while fans fell in love with the characters and the setting. Essayists have gone into great detail about the game, its themes, and how immaculate the experience is as a whole. Many spectacular titles were released within the seventh generation of console gaming, but many insisted The Last of Us blew every single one of them out of the water. That it managed to somehow surpass Uncharted 2 in terms of accolades is no mean feat. Was Mr. Druckmann able to use his determination over the better part of a decade to create something that stands not only as Naughty Dog’s magnum opus and the seventh generation’s swansong, but also one of the greatest games ever made?

Playing the GameWARNING: This entire review will contain unmarked spoilers. If you are at all interested in playing The Last of Us, skip to the conclusion.

The Last of Us boasts varying gameplay elements, but at its core, it’s a third-person shooter set in a zombie infested, post-apocalyptic America. People having first experienced Uncharted or any other similar title will quickly learn than the tactic of taking damage and hiding will not work in this game. This is because you have a health meter; therefore, if you take damage, don’t expect to regenerate even when you find a safe spot. Only through the use of a first-aid kit can you recover from the various injuries you will accumulate over the adventure. The meter is divided into segments, and as you’re patching yourself up, it will gradually fill. Once the empty segment is completely filled, you will have recovered that much health. This process works in real time, so make sure the enemy isn’t aware of your location when you decide to do it.

The game further distances itself from the familiar third-person gameplay of Uncharted by including survival horror components. Although combat is unavoidable, there is a great emphasis on resource management. There is a limited amount of weapons you can have equipped at a given time, but you do not simply toss aside old ones with reckless abandon. Every time you happen upon a new weapon, your character will place it in his backpack. Naturally, you can’t use weapons when they’re in the backpack, but you can still collect ammunition for them. You’ll want to make every attack count because ammunition can be difficult to come by. This is a game in which you will often need to switch weapons not only to suit the situation, but also because it’s the only chance you have.

Stealth is subtlety encouraged by the protagonist of this game being less survivable than Nathan Drake and other contemporaries; you would do well to exercise caution whenever hostiles appear. It might be a better idea to sneak up on enemies and take them out silently than to go in guns blazing. To make this easier, you can press a button while concealed from the enemy to detect their movements even through walls and other impassible barriers. The sounds they make will give your character an idea of where they are. In gameplay terms, this is represented by your foes appearing as white silhouettes. This feature is unavailable to you on harder difficulty settings.

When it comes to weaponry, you’re not limited to professionally manufactured firearms. In a pinch, you can resort to fisticuffs or melee weapons such as baseball bats and lead pipes to defeat your foes. Melee weapons kill enemies faster, but they have limited durability. If you so choose, you can also use materials such as alcohol, blades, and explosives to craft your own weapons and items. You can manufacture Molotov cocktails, shivs, health kits, nail bombs, and smoke bombs. The crafting system can also be used to upgrade melee weapons so they will inflict more damage per hit. It takes a sharp mind to survive in such a world, and knowing how to work with unexpected results is a skill you’ll develop very quickly playing this game.

Although The Last of Us is not a role-playing game, elements of the genre have been woven into the experience. Littered throughout are supplements that come in the form of pill bottles and potted flowers. Consuming these will increase the number of reserved supplements, which can be used to enhance the protagonist’s prowess in combat. Depending on how you allocate the points, you can opt to increase his health, listen mode distance, crafting speed, healing speed, weapon sway, or shiv mastery. The last item on the list allows you to expend a shiv to save yourself from a zombie capable of causing instant death.

Despite being a new IP, Naughty Dog’s attention to detail when it came to crafting environments shone through. The developers encourage you to explore these lovingly rendered set pieces by hiding a large array of collectables. You can find artifacts, comic books, pendants belonging to a secret organization, and training manuals. Artifacts could include notes, personal belongings, audio logs, or other items that give insight to the state of the world. Comic books and pendants similarly serve no practical purpose, but they do result in a few unique reactions from the secondary protagonist. Training manuals enhance the protagonist’s proficiency with various items. Depending on what you find, he can heal himself efficiently with health kits or inflict more damage with certain weapons.

Within a few minutes of The Last of Us beginning in earnest, it’s clear Naughty Dog put quite a bit of thought into the gameplay. Unlike in the Uncharted series where the enemies will gleefully run into your line of fire and generally display little to no survival instincts, The Last of Us opted for a nuanced, subtle approach to enemy behavior. Among other options when fighting human enemies, you can throw objects to distract them, hide, duck for cover, take their firearms, and hurl improved weapons such as Molotov cocktails. Normally, this wouldn’t bear repeating, but it should be noted that the enemy is perfectly capable of employing these tactics as well.

Moreover, if you’re spotted, they will call for reinforcements, yelling something to effect of “He’s in here!” or “He’s by the door!” as the situation would warrant. If you do fail at staying out of the enemy’s sight and manage to get away or resolve the immediate threat, the survivors’ patrol routes become more unpredictable as they begin to investigate blind corners. They will use their superior numbers to a good effect, often swarming the player character from all sides, making it ill-advised to remain in one spot for too long. It’s also not a good idea to fire a gun if you’ve depleted its ammunition, for if they hear it click, they will become more aggressive.

With its resource management and prominent undead foes, I invariably end up comparing The Last of Us to Resident Evil 4. The Last of Us was originally released in 2013 – eight years after the highly celebrated Resident Evil 4 saw its debut in the public eye. Thus, one could assume that such a significant length of time would allow Naughty Dog to study Capcom’s masterwork and maybe even improve on some of the components which haven’t held up well with time.

To begin with, The Last of Us doesn’t have much in the way of quick-time events, which is appreciated, as they were the worst trend to result from the success of Resident Evil 4. It further differentiates itself by featuring a real-time inventory system. When I first learned this, I dreaded that it would lead to several cheap deaths. Luckily, as long as you prepare your loadout before you get into a fight, you’ll have pretty much everything you need to survive. Even if you need to make another item during an encounter, there are usually enough safe places that you probably won’t get killed in the process – provided you exercise common sense.

I also give Naughty Dog credit in that The Last of Us features more variety than Resident Evil 4 or, indeed, their own Uncharted series when it comes to level design. The story takes place over the course of a year, encompassing each of the four seasons. The summer portions have the protagonists exploring dilapidated, manmade structures while the winter segment begins with one of them hunting for a deer so that the two of them may survive the inclement conditions. Mr. Druckmann and his team did a fantastic job incorporating these levels into the narrative, simultaneously increasing their diversity while presenting them in such a way that it will leave an impact on those who play it.

Unfortunately, as great as these ideas are, they end up making for a rather bland game that only barely sticks out from its contemporaries. By 2013, shooters regularly topped the sales charts. Naturally, this was due to a few success stories such as Call of Duty and Gears of War. It was hardly a new trend, as there were innumerable 2D platformers of varying quality after Super Mario Bros. debuted in 1985 and became a cultural phenomenon. In both cases, the genre became oversaturated to the point where even the good, original games could risk being lost in the sea of banality.

The bitter irony is that when The Last of Us does stand out, it’s for all of the wrong reasons. One major difference between Resident Evil 4 and The Last of Us would be how they save progress. The former relies on save points while the latter opts for a checkpoint system. In my opinion, one of the worst aspects about checkpoint systems is that in many cases, it’s clear the developers didn’t bother polishing the gameplay to the extent where it feels like a reasonable challenge. Granted, it is annoying having to find a save point whenever you wish to quit playing, but in practice, they seem to enforce good game design better than the alternative. This is because developers have to determine whether or not the stretches between save points are feasible to complete in a single session. If it isn’t, they must either add another one or otherwise do something to balance out what is perceived to be insurmountable. When the game saves automatically between or during important developments they need only to make sure each section can be completed at all – even if the player needs to restart ten times to do so.

As a tangential consequence to featuring checkpoints, The Last of Us is a game whose creators didn’t understand the difference between challenge and annoyance. To soften the blow a little bit, I will yield that this observation applies to any of the Uncharted games – especially in each entry’s later levels where it was clear Naughty Dog spent less effort. The reason I’m lodging this criticism towards The Last of Us is because the slower pace means each mistake wastes more time than a comparable blunder in Uncharted. At the worst of times, it’s actively not fun to play.

In your travels, you will encounter zombies known as clickers. The gimmick behind these enemies is that they are blind, but have superhuman hearing. Punching them is ineffective, so only firearms and melee weapons can bring them down. Normally, this would be slightly irritating, but Naughty Dog went a step further by giving them the ability to kill the protagonist with a single attack should they get ahold of him. This isn’t a terrible idea by itself, but I wound up dying to these enemies more than I did to any other type combined – including humans. Theoretically, if you’re quiet and throw bricks to distract them, you can sneak through without being noticed. In practice, there are dozens of situations in which you will get attacked by hordes of zombies – clickers included – and it’s impossible to be silent. There were several instances in which I was doing well against in a fierce melee only for a clicker to leap from offscreen, killing my character instantly.

Here we see Naughty Dog forgetting what the point of a health bar is.

As a counterexample to prove it can be done well, Resident Evil 4 also had no shortage of enemies capable of felling the player character in one attack. However, there were three key differences which made dealing with them far more tolerable. For starters, they were more obviously dangerous. A crazy person charging at you with a chainsaw is going to get your attention even when there are several other enemies onscreen. Secondly, you don’ t have to resort to markedly different tactics to defeat them; you may have to hit them while they’re down, but that’s not unreasonable. Finally, and most importantly, they’re not as common as clickers are in The Last of Us. The takeaway from this is Shinji Mikami and his team at Capcom made it so that you would only fall victim to these foes if you well and truly lost control of the situation. When describing the design ethos Mr. Druckmann and his team adopted, I would either compare it to classic adventure games from the eighties that kill players for not being clairvoyant or, less charitably, the NES version of Dragon’s Lair.

Exacerbating matters is that the shooting is decidedly imprecise. The creators at Naughty Dog have never been frontrunners in this regard, as the Uncharted series also featured somewhat loose aiming mechanics, but wasting ammunition wasn’t a pressing issue due to its abundance. With The Last of Us, bullets are uncommon enough that expending them unnecessarily is immensely crippling. With certain upgrades, you can decrease the protagonist’s weapon sway, but this leads to another problem: at no point in the narrative is it suggested that he is a terrible shot. Indeed, a development towards the end of the game outright proves this isn’t, and never was, the case.

To sum up The Last of Us in terms of gameplay, I think it manages to be a mishmash of legitimately good ideas interlaced with several awful ones that bog down the experience. All in all, it comes across as a watered down version of Resident Evil 4, lacking both the imagination in enemy types and creativity with the level design. Although Resident Evil 4 had fewer environments, they were all beautifully fleshed out and built on each other. With The Last of Us, you explore a small, unremarkable area, and move on to the next, completely abandoning any meaningful cohesion between them.

Then again, anyone who enjoyed The Last of Us knows I’ve only described half of the experience. Many of them would even argue I assessed the less important half, and that the true value of this game lies in its immaculate story. I think it’s about time I started touching upon the real reason The Last of Us shook gaming culture back in 2013.

Analyzing the StoryIn the year 2013, Sarah was a 12-year-old girl from Austin, Texas living with her father, Joel. On the eve of his birthday, pandemonium broke out as humans across the United States begin succumbing to a brain infection originating from an unknown fungus. Those infected were doomed to lose all sense of reason and self, attacking others in an animalistic rage. Some would call them zombies. Sarah made her escape alongside Joel and her uncle, Tommy. She and her father got separated from Tommy as he helped hold the infected at bay. During their flight, they encountered a lone soldier who had orders to fire upon them. Before he could execute Joel, Tommy shot him in the head. Tragically, Sarah was fatally wounded by the soldier’s initial salvo and died in her father’s arms.

Twenty years have passed since that incident, and Joel now resides in a bleak, post-apocalyptic Boston. The city is a far cry from the bustling metropolis it once was. The fall of civilization transformed it into a military controlled quarantine zone under martial law. The military has orders to kill any infected human on the spot and ration cards are required to obtain sustenance from them. Whenever there’s a shortage, the authorities will declare half-ration weeks, which can last for an entire month or more. The able-bodied citizens are conscripted with drafting notices being distributed every six months.

Joel now makes a living as a smuggler, illegally trading with other survivors outside of the city. His partner and friend Tess explains to him that, after having come back from a deal with another client, she was jumped by two men who threatened to kill her. Soon thereafter, they seek out an arms dealer named Robert who had stolen guns from them. Upon confronting him, he revealed that he sold their firearms to a paramilitary group known as the Fireflies. An angered Tess shoots him in the head, and she and Joel set out to retrieve their belongings.

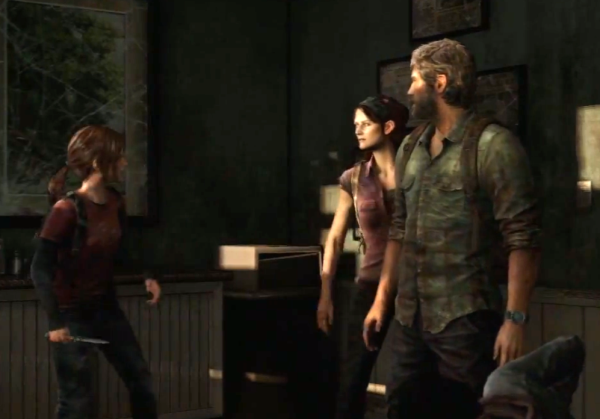

After confronting the organization’s leader, Marlene, she strikes a deal with the two of them. She will part with the guns and double the payment in exchange for smuggling something out of the city for her. It’s revealed at a safehouse that they will be escorting a young girl named Ellie to the Capitol Building where the Fireflies. Ellie was bitten three weeks prior to the game’s beginning, but she had yet to turn while a typical infected person would lose themselves within two days. Marlene explained that her unique condition could be the key to synthesizing a cure for the infection which brought humanity to its knees. The Capitol Building turns out to be infested with hordes of infected humans. They break in only to learn that the Fireflies they were supposed to meet are all dead. To make matters worse, Tess was bitten in the fight, and she only has a day before she herself turns. She sacrifices herself to hold off a group of soldiers, allowing Joel and Ellie to make their escape. Now they must travel across the zombie-infested land to the University of Eastern Colorado where the Fireflies now reside. Only their wits will allow them to survive the perilous journey.

It is nearly impossible to understate how universally heralded The Last of Us was upon its release in 2013. Indeed, arguably one of the only other games that can claim to have received such a reception would be Naughty Dog’s earlier effort, Uncharted 2. Critics fell in love with the game’s story, citing its complex character development, profound social subtext, and masterful presentation. The press considered one of the medium’s most significant accomplishments, for it was believed to have broken the industry’s conventions in order to deliver a truly mature, adult plot that showed how much video games had grown up since the golden age in which they featured stories no more complicated than “Save the princess” or “Kill the bad guy so he can’t do bad things anymore”.

I played The Last of Us within a few months of its release, and by then, I was no stranger to story-heavy games. Earlier in 2013, I experienced the first two installments of Kotaro Uchikoshi’s Zero Escape series and before that, I played through Chris Avellone’s Planescape: Torment. Since then, those titles are invariably the ones I will mention whenever I’m recommending games with strong writing. Having established this, some people may be wondering how I think The Last of Us fares when compared to those three games. I have a definite answer to that hypothetical question, but I feel it would make little sense without explaining my thought process, so it’s best to start from the beginning.

In the seventh generation of console gaming, Naughty Dog had proven themselves masters when it came to presentation. The post-apocalyptic world has a similar quality to the one depicted in Fallout 3 in that it is equal parts beautiful and sorrowful to look at. There’s a tranquil quality to the world, yet when you consider what transpired for it to reach that state, the enormity sets in.

Perhaps the biggest curveball Mr. Druckmann pitched when designing this game would be with the character of Ellie. Those not examining the promotional material too closely would assume Ellie is the token defenseless little girl meant to be protected from the big bad world and evoke sympathy from the audience. This couldn’t be further from the truth – she’s a valuable asset in combat by being every bit as capable of shooting or stabbing enemies to death as Joel. As for her personality, all I can say is that hearing her introductory dialogue laced with multiple profanities caught me completely off-guard the first time around. It’s a tad gimmicky, but I think it succeeds in making her a memorable character – possibly more so than Joel considering his many similarities to the average action-game protagonist at the time.

Furthermore, the performances are absolutely top-notch, and they bring the characters to life. Whenever a tragedy occurs, the inflections betray a sense of real pain. So passionate were the voice actors that they reportedly broke down in tears during certain takes. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the prologue. Troy Baker’s delivery as Joel helped sell the character’s deep emotional trauma, and it could very well be the most convincing death scene in any game I’ve ever played.

The writing isn’t without its flaws, however, and the story’s first misstep occurs within that scene. Powerful though Sarah’s death scene may have been, Mr. Druckmann was in too much of a hurry to kill that character off. Consequently, we know nothing about Sarah outside of a few hints. If he wanted the death to have a real impact, he should have established why we should care about these characters before allowing the situation to spiral out of control. That way, we’re more likely to feel something when bad things happen to them. This problem could easily have been fixed by extending the prologue to develop both Joel and Sarah as characters. The developers could have then peppered this section with action sequences, culminating in a tragic scene at the end where Joel was unable to save Sarah from a surprise attack or from being infected by the deadly fungus. Instead, the significance of her death lies in the fact that she was the protagonist’s daughter and a minor to boot. It’s a heartrending, poignant, yet wholly unearned moment.

A few fans were quick to declare The Last of Us the Citizen Kane of gaming, but what I think Mr. Druckmann and his team inadvertently created was the medium’s equivalent of District 9. On the surface, it may sound like a superfluous statement because all I did was swap one critically acclaimed film for another. Although both works are indeed highly regarded, I did have a reason for doing so. Chief among the problems plaguing District 9 was how it forced the audience to accept a completely unbelievable premise, negating any value it had as a thought-provoking satire. It wanted us to believe the same species that created entire trade networks to obtain silk would throw aliens in the slums at the first given chance – in the eighties when space travel and science fiction were all the rage, no less.

How does this relate back to The Last of Us? I will admit its premise isn’t as blatantly stupefying as that of District 9, but it does suffer from a similar issue. The presentation constantly suggests that the species is barely hanging on by a thread. One would then assume under such circumstances that human life is even more valuable than it was before the outbreak. Being in dire straits doesn’t prevent anyone from executing fellow humans on the spot – often for impulsive reasons. The only reasonable conclusion one could draw from this information would be that people must be better off than the narrative insists. Otherwise, if the body count by the endgame is indicative of life in this world, there is no way that the humans presented in The Last of Us could possibly have lasted for twenty years without driving each other to extinction. Alternatively, if real-life humans were one percent as horrible as those presented in The Last of Us, they couldn’t possibly have formed any kind of civilization. I understand that fighting enemies who can shoot back is more fun and dealing with zombies would get boring after a while, but you can’t have it both ways. By the end of the game, I was left wondering who The Last of Us could possibly refer to – it’s certainly not humans.

This leads into an issue regarding the leads themselves. There was a persistent criticism regarding the Uncharted series involving its protagonist Nathan Drake. Specifically, a vocal cabal of critics insinuated that he is a carefree mass murderer for gunning down hundreds of men in each of his games with nary a single moment of contemplation to be found. I don’t agree because Uncharted isn’t grounded in reality to an extent where that would be problematic, but I think it’s a completely valid point, and it showcases a major weakness with this brand of storytelling.

As The Last of Us features a similar story presentation to the Uncharted series, some reading this may be wondering if I think it fares better in bridging the divide between story and gameplay. The answer is that it does and doesn’t at the same time. It’s as though Naughty Dog caught wind of the criticism lodged towards Nathan Drake and the Uncharted series, but didn’t fully grasp why it was formed in the first place. On one hand, Joel is presented as the type of person who wouldn’t hesitate to kill someone if they proved a significant enough hindrance, making him an ideal protagonist for a shooter game. On the other hand, Naughty Dog ended up fixing one problem only to introduce a new, worse one. Because Joel has no qualms about gunning down humans in a setting that implies they’re not doing so well, it’s even easier to make him and Ellie out to be sociopathic monsters than Nathan Drake. The only other option would be admitting the narrative oversold the zombie threat, thus shooting holes in their own premise. In other words, for the fourth game in a row, Naughty Dog elected to write in a way that barely acknowledges the medium. It’s to the point where if you showed the cutscenes to an unaware person, there’s a good chance they would assume they’re clips of an unfinished 3D animated film. They likely wouldn’t even entertain the idea that they were meant for a video game.

Despite all of the praise the writing received from the press and fans, I find it’s not really a marked step up from the Uncharted series in a vacuum; the only real difference is that the characters swear more often. It’s as though The Last of Us was conceived by having a team go down a list of common tropes in Academy award-winning films throughout history and checking every box. The result is a work that’s a little too safe for its own good. Even people with little-to-no knowledge of the zombie apocalypse genre can correctly predict where the story is heading at any given moment. I myself remember one point in which Joel and Ellie were given a horse, and I figured it would die within a couple of hours. The fact that it does is so obvious, I wouldn’t have had to use tags if I were to write a spoiler-free version of this review.

To be fair, it’s not as though The Last of Us is wall-to-wall clichés. After all, Ellie is quite an atypical character, running counter to the trends in AAA gaming at the time. This was completely intentional on Mr. Druckmann’s part. In an interview, he once said, “I wanted to create one of the coolest, non-sexualized female video game protagonists. And I felt that if we did that, there’s an opportunity to change the industry. I know it sounds pretentious, but that was my goal.” It’s a noble sentiment, but there’s one moment that manages to dash most of the goodwill Naughty Dog had so carefully established.

In the winter scenario, Joel has been injured and they must lay low until he recovers. It provides an interesting reversal of roles, as Ellie must fend for him. At one point, she happens upon a group of people who initially seem on the level, but because this is The Last of Us, it naturally turns out they’re evil cannibals. She is captured by them after supplying Joel with antibiotics. To give credit where it’s due, I admire that she manages to escape on her own rather than having Joel make a miraculous recovery to save her at the last moment. Where this vignette lost me was how it ended.

It culminates in a pseudo-boss battle against the head cannibal, David. Throughout the Uncharted series, Naughty Dog did not demonstrate aptitude in developing boss fights. Whenever Nathan Drake encountered that game’s antagonist, the writers had to jump through hoops to justify why the player can’t simply end the conflict three hours in. This led to many irritating moments involving the antagonists escaping through progressively more convoluted means as the games continued.

I will say that this is one of the few areas in which Naughty Dog improved, though they didn’t exactly fix the problem as much as they avoided dealing with it entirely. Because The Last of Us doesn’t feature an overarching antagonist, it was easier for the writers to dispose of villains once they were no longer needed. However, this annoying propensity came back with a vengeance in the form of David. Ellie lost her firearms, and she must navigate a burning, abandoned luncheonette and stab in him the back a certain number times. This battle involves stealth, and you must be careful to avoid any fallen dinner plates, as they will alert him to Ellie’s presence. If David finds her, he will fell her with a single strike of his machete.

“We don’t take kindly to health bars ’round these parts.”

Once again, Naughty Dog took note of Ellie stabbing him the required number of times and declared that the player’s input doesn’t count. Instead, Ellie and David get in a tussle and are both knocked out. Ellie regains consciousness and tries to retrieve David’s machete, but he wakes up, kicking her several times before pinning her to the ground. Before he can act, Ellie grabs the blade and violently hacks David’s face with it, killing him. After that, runs into the arms of a barely recovered Joel and bursts into tears.

It’s implied that David attempted to rape Ellie considering he stated, “You have no idea what I’m capable of!” while she was in his grasp. To put it lightly, this was an incredibly poor decision on the writing staff’s part. Sexual assault is one of those concepts you have to fully grasp in order to properly implement it in your story. Some of the greatest writers who ever lived would have a difficult time implementing the idea without making audience members want to roll their eyes and I can’t say anyone who worked on this game is a member of that group. A select few critics even decried this scene as an example of the alleged sexist attitudes permeating throughout the medium at the time. I’m not sure if I would call it sexist, but there is a real air of chauvinism to it, and it is very much a product of its time as a result. What I definitely believe is that, along with Sarah’s death, it’s an attempt on Naughty Dog’s part to seem mature and serious while succeeding at being neither.

Dissecting the EndingIn a normal game, a poorly-handled attempted rape scene would be its low point. In The Last of Us, it turned out to be a mere prelude to what was to come. This is because the ending ranks among the worst I’ve ever seen from a story-heavy game. In the interest of fairness, this too wasn’t unprecedented. By 2013, Naughty Dog could not boast a stellar track record when it came to giving their works proper sendoffs. All of the Uncharted games suffered in some way during their respective second halves. However, The Last of Us would go a step further, and the only way I can properly articulate how the ending fails is to go through the final sequences step by step.

After having traveled across the country to Salt Lake City, Utah, Joel and Ellie finally discover the Fireflies’ hideout. Upon arrival, they are rendered unconscious by a guard. Joel wakes up to discover Ellie missing. Marlene explains to him that in order to create a vaccine for the fungus, they must euthanize Ellie. Unwilling to accept that losing Ellie would mean effectively reliving the death of his daughter, Joel wrestles a gun away from a soldier, shoots him in the groin, and demands to know where they took her. He complies, but Joel kills him regardless, and the final hours of the game involve navigating the base alone, shooting any militiamen along the way. I do like that you are given an assault rifle for this sequence, but this is where the gameplay arguably suffers the most. Relying on its unpolished shooting mechanics transformed the game from a reasonably paced survival horror to a subpar Uncharted clone.

It doesn’t help that the setup is convoluted as well; I once discussed the ending to this game with a friend who has some medical knowledge, and he questioned why they even needed to euthanize Ellie when some of the fungi was clearly poking out of her skin. This wasn’t their first scientific gaffe, as characters insinuated that clickers sense humans through echolocation. If that were true, being quiet wouldn’t help at all. It doesn’t make any logical sense, but that can least be justified by the developers wishing to sacrifice the story for the sake of gameplay. However, it becomes troublesome when their lack of knowledge drives the plot. To make myself clear, I don’t expect writers to be scientifically accurate all the time, but the problem is Naughty Dog often writes in a way that adheres to reality until it becomes inconvenient for them. This causes the unrealistic components of their stories to stick out like a sore thumb to the point where it would test anyone’s suspension of disbelief.

This is a problem, but the source from which I draw even more umbrage concerns how the ending forces you to gun down people who want to cure a disease that has been the bane of humanity’s existence for twenty years. This failure is compounded when Joel eventually makes his way to the hospital room and is confronted by a doctor armed with a scalpel. As you can’t get past the doctor while he’s alive, you must manually take out a weapon and shoot him. This prompts his ally to call Joel, and the player by extension, a monster. This moment encapsulates the most insidious part about Naughty Dog’s writing. Over the course of four titles, they were content to ignore their audience’s input in favor of crafting a static story, but when the protagonist must commit a heinous action during gameplay, all of a sudden, the player is part of the experience. They are then chewed out for the crime of wanting to clear the game that several publications called one of the medium’s greatest technical achievements.

“Do you feel like a hero ye- Oops, sorry, wrong game.”

For some unfathomable reason, many AAA artists in the 2010s had an insufferable habit of openly disrespecting their audience, and like the confrontation with David, this moment marks Naughty Dog’s work as a product of its time in the worst possible sense of that term.

With an unconscious Ellie in tow, Joel makes it to the base’s underground parking lot where he confronts Marlene. Defying all semblance of common sense, she actually surrenders her own weapon in order to talk things over peacefully with Joel. The latter responds by shooting her in the head a mere second after she begs for her life in the face of certain death – Joel’s reasoning for doing so being that she would only pursue them. When Ellie wakes up, Joel makes up a story, saying the Fireflies had given up on making a cure and that dozens of immune people like her died needlessly in their attempts to make one. She later asks him if he’s lying and he assures her he is not. She hesitantly accepts his answer.

Whatever extremely minuscule amount of sympathy I may have had for Joel was dashed as soon as he uttered those words. It makes sense why he would be fiercely protective of someone who essentially became his second daughter. The problem is that, in this particular instance of being protective, Joel metaphorically spat in the eye of every single human being on Earth by depriving them of a cure for a horrifying fungus. One could infer that after losing his daughter and fighting humans for such a long time, he had enough and thinks they’re monsters no longer worth saving. This makes him hypocritical as he embodies all of the traits he hates humanity for: selfishness, treachery, and no regard for the lives of others.

When the story began, Joel was no better than a one-dimensional thug one would gun down with impunity by the hundreds in any other action title. Indeed, I remember at one point him mentioning that he had been on both sides of an ambush, implying he’s no better than the bandits he gunned down throughout the game. Although it was clear he would never return to being a cheerful person, I wanted to see him rise above his vices. This sequence managed to undo all of his character development, making the entire experience an exercise in futility. It’s to the point where I questioned why I even helped him survive.

Despite this, some fans have defended Joel, saying that he was justified in what he did in the endgame. Normally, I would think of such an assertion as farfetched, but they do have evidence to back up their claims. There is an audio recording you can find when exploring the Fireflies’ base. According to the person who recorded the message, the doctors had discovered several people immune to the fungus, but when they euthanized them, they were unable to synthesize a vaccine. This suggests that they had no idea what they were doing and their desperation grew with each unnecessary death. Although it may seem as though Joel saved Ellie from a group of people driven insane by their actions, it’s not that straightforward. The information contained within the log is not in any way, shape, or form worked into the narrative. Most damningly, the final exchange between Joel and Ellie isn’t altered by finding it. His lying of the circumstances surrounding Ellie’s rescue could have been a powerful, if controversial moment, but the audio log renders it entirely nonsensical; he could have just played the recording after they escaped and avoided any drama altogether. It’s possible he lost or broke it during the escape, but even if he did, he had no reason to lie. In short, that recording, for all intents and purposes, is on a different plane of existence from whichever one the actual story resides.

It’s as though the developers realized halfway through conceiving the ending that Joel’s actions were unsympathetic and decided to include the audio log to justify them. All it effectively does is convey the lack of conviction on the writers’ behalf. They wanted to create a situation where it’s unclear who, if anyone, is in the right, but they backed out by painting the Fireflies’ actions as outright evil. One prominent gaming critic pointed out how Naughty Dog had a bad habit of dehumanizing everyone outside of the leads, and playing The Last of Us made me realize exactly what he meant by that. The narrative held nothing back whenever it insinuated that people are just no good, yet the protagonists are only slightly better than the people they fought. There is a fair bit of cognitive dissonance whenever an author relentlessly professes misanthropic viewpoints while also expecting their audience to empathize with their human characters. At that point, the message of the story seemed to be: humans are horrible, but be sure to make an exception for the ones who count. It lends a narcissistic feeling to any the game’s heartwarming moments.

I had been alluding to the story’s fatal flaw throughout this review, but now that I’ve established the proper context, my primary point will be made clear: the switch to a mature, serious tone only magnified Naughty Dog’s weaknesses as both writers and game designers. All of a sudden, many of their quirks, which were minor irritations at worst, suddenly became untenable. Getting torn apart by a clicker is a horrific sight to behold, yet any shock value is replaced with annoyance when you’ve fallen to them fifty times already. One-dimensional antagonists work in a story that runs on black-and-white morality, but fails in the face of moral ambiguity. Putting less effort into the second half of the game isn’t too bad of a mistake in a non-serious story, but it’s a glaring one when you’ve crafted a narrative so heavily focused on its characters. The player had no bearing on the plot until the writers could shamelessly guilt-trip them only for them to become irrelevant once again immediately afterwards.

Finally, I should mention that since the release of The Last of Us, an event occurred which retroactively made many of these issues worse. As much as I didn’t like it, I do think Mr. Druckmann and his team created a suspenseful situation in which they successfully threw the protagonists’ continued survival into question. Its death knell was sounded the moment a sequel Naughty Dog announced a sequel, for the promotional materials thereof prominently featured an older Ellie, and staff members confirmed that Joel would return as well. Therefore, no matter how much the narrative stresses that the main characters are in danger, anyone who plays the game after the year 2016 will know their survival is a foregone conclusion, thus ruining any tension. Irony of ironies, the extensive press coverage Naughty Dog games received at the time ultimately worked against them. There’s also the fact that any friction between Joel and Ellie in the sequel will be the result of these bouts of sloppy writing. This is the reason I can confidently say The Last of Us has one of the worst endings in video game history. Such is the extent of its awfulness that it actively sabotages its sequel.

Drawing a ConclusionPros:

|

Cons:

|

There’s no getting around it; The Last of Us is one of the most disappointing games I’ve ever played. When I first heard of the enthusiastic praise surrounding it, I was looking forward to the prospect of experiencing a mature Naughty Dog title, but in reality, they retained their trademark quirks and shortcomings; the only difference is that they opted for a moodier tone. Having played a handful of games whose authors put a lot of care and attention into the story, I can say beyond any reasonable doubt that The Last of Us is not comparable to the likes of Planescape: Torment or Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors.

When it comes to this game’s writing, Naughty Dog struck me as complacent in being only slightly better than their peers in the AAA industry rather than striving to be genuinely great. It would be like if Roland Emmerich entered a filmmaking competition where his only opponents were high school students. Film critics pretty much universally agree that as successful as his movies have fared in the box office, he is not one of the medium’s better directors.

How bad was he? He couldn’t even fire a shot at his most vocal opponents without them criticizing his technique.

However, in this hypothetical scenario, his work would almost certainly sweep the competition with little effort unless he found himself face-to-face with an exceptionally talented team of filmmaking students with an improbable access to cutting-edge technology and talented actors. To put it another way, he would be the proverbial one-eyed man in the land of the blind. After playing The Last of Us, I became convinced Naughty Dog’s situation wasn’t dissimilar.

When I first completed this game, I believed the unanimous love it received was the result of Naughty Dog transplanting stereotypical award-bait tropes into their work, but upon reflecting on it for a while, I think there’s a little more to it than that. In 2010, esteemed film critic Roger Ebert proclaimed that video games can never be art. It was a very unfortunate position for him to take considering how he was part of a new wave of critics in the late sixties whose opinions would challenge the status quo of what constituted art in film. Among other accomplishments, in 1967, he gave a positive review to Bonnie and Clyde while his peers dismissed it for its violent content. His opinion stood the test of time, as the film has since been declared a turning point for the medium. His later assertion regarding video games was already provably unsound considering humanity’s adoption of the written word and all of the significant advancements that came with it, defying the ancient Greek philosophers who believed it would cripple one’s memory.

Enthusiasts had to contend with people dismissing their hobby as children’s toys before, but hearing a man whose opinions carried a significant amount of weight expressing a similar belief, even if it was demonstrably wrong, nonetheless added insult to injury. It especially didn’t help when Braid and other titles considered heavy-hitting, quintessential art games at the time utterly failed to move him. Fans had been self-conscious about the medium they enjoyed throughout the 2000s, but this statement made them redouble their efforts. On the surface, The Last of Us would appear to provide the perfect solution to this conundrum because it has all of the makings of a mature, adult story, and was made in a time when the medium, by and large, lacked self-respect. In the end, it didn’t escape the trappings of the 2010s AAA climate. To clarify, I don’t believe Mr. Druckmann and the rest of Naughty Dog intentionally took advantage of the community’s insecurity, but it’s difficult to falsify the idea that it worked in their favor.

With everything being said, I sympathize with the people who refused to find fault with the game when it was first released. For many of them, their entire notion of whether or not video games were art was predicated on The Last of Us being a masterpiece. Had there been any flaws in that premise, it would mean video games getting knocked back to square one, wherein they would continue to be shunned by the mainstream. The Last of Us being less than perfect is an easy reality for someone to accept when they believe the medium has always been a form of art, but it’s plain to see why anyone else would find it a difficult pill to swallow.

At the end of the day, the best story-heavy games take full advantage of the medium in order to weave a narrative that couldn’t be replicated anywhere else. The Last of Us is a textbook example of a narrative that does not benefit from being in a game. When combined, the individual components of the experience form something less than the sum of its parts. I liken it to someone trying to assemble a puzzle using pieces from several different boxes. That person might end up constructing a rectangle and parts of the finished product may look good when inspecting them up-close, but when you take a step back and look at the entire picture, you get an ugly, contradictory mess. If the story was surgically removed from the game, its biggest issue would be fixed, but then we would be left with a zombie movie where the subtext is that humans are the real monsters. It wouldn’t exactly break new ground considering George Romero explored similar themes before Mr. Druckmann was even born.

Uncharted 2 may not have been a masterpiece, but it will always rank higher in my book because of its exhilarating gameplay. It remains a breath of fresh air in a time when games were starting to take themselves too seriously. Would you rather hang on a road sign and shoot at evil mercenaries or watch a family man lose his daughter? Did I even have to ask?

Final Score: 3/10

Advertisements Share this: