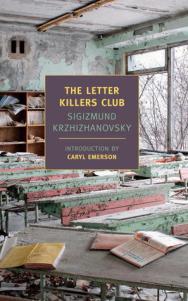

Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsk’s novel, The Letter Killers Club, opens when an un-named narrator informs us he has been invited to attend the weekly meeting of seven well-respected authors. The author’s have come to the conclusion, most of them late in their careers, that by writing down their ideas they prevent others from having them. So instead of writing, they now meet once a week to tell stories to each other.

Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsk’s novel, The Letter Killers Club, opens when an un-named narrator informs us he has been invited to attend the weekly meeting of seven well-respected authors. The author’s have come to the conclusion, most of them late in their careers, that by writing down their ideas they prevent others from having them. So instead of writing, they now meet once a week to tell stories to each other.

The rest of the novel consists of the narrator’s account of the ideas and stories shared at the meetings.

It’s a very interesting book.

The introduction states that Mr. Krzhizhanovsk is a writer interested in ideas rather than characters and plots. Judging from The Letter Killers Club I agree, to a point. While the novel is full of ideas, many of them wonderful, some of them over my head, there is still a plot and there are still characters.

The plot centers around the idea of silence and a commentary on it. The conflict of the novel adressess the question of how do you write about silence. What can you say about the absence of words? This question goes back to the origins of the club itself.

The club’s creator tells the narrator how he came to be an author. As a young man he had a prized collection of books, great works, that he read again and again. Due to a family emergency he was forced to sell off his collection leaving him with an empty bookcase. He began writing to replace the missing books. Each of his own works is simply his attempt to retell the stories in the books he had to sell. Eventually, he realized that be setting down ideas in print, no one could ever have those ideas again. They were his. People could encounter them in his books, but they could not discover them.

I think that’s brilliant.

I suspect that the ideas Mr. Krzhizhanovsk presents in The Letter Killers Club must have had special resonance in his native Russia where he lived under Communist dictatorial rule. The question of whether or not stories once written prevent people from forming their own ideas seems like a profound comment on a culture that repressed speech the way the U.S.S.R. once did.

But that’s one question I’ll have to leave to people better informed than I am.

What I loved about The Letter Killers Club can be found in this, slightly long, passage about the student who tried to write the commentary on silence. Once he finished his work, or thought he had finished it, he purchased a very old copy of the Bible. In it, he found the word “S-um” written in the margin. Intrigued, he begins looking for other marginalia.

Running an eye down the Vulgate’s margins, he noticed another mark in ink bracketing two verses: “Behold my servant, whom I have chosen….” and so on, and “He shall not strive, nor cry; neither shall any man hear his voice in the streets.” A vague presentiment compelled him to scan the margins with more care, page by page; three chapters later he found the faint score of a fingernail: “…O Lord, thou son of David; my daughter is grievously vexed with a devil. But he answered her not a word.” the margins that followed appeared to be blank. but the composer of Commentary on Silence was too intrigued to abandon his search; examining the pages in the light, he discovered several more marks grown faint, the work of someone’s sharp fingernail–and opposite these: “And when he was accused of the chief priests and elders, he answered nothing. Then said Pilate unto him, Hearest thou not how many things they witness against thee? And he answered to him never a word; insomuch that the governor marveled greatly.” Or: “But Jesus stooped down, and with his finger wrote on the ground, as though he heard them not”; some marks could be seen only with a magnifying glass, others stood out; some where shorter than a dash and picked out only three or for words–for instance, “And he withdrew himself into the wilderness…” or “But Jesus held his peace”; others extended down a series of verses, setting off whole episodes and stories–and every time it was a story about questions never answered, about a silent Jesus. That of which the old St. Gall Neumes spoke as though stammering, but spoke all the same, was marked and scored–with fingernail skipping words to the end. Now it was clear: on the yellowed pages of that tattered tome, beside the four who had spoken, a fifth Gospel with no need of words was giving forth from the book’s blank margins: The Gospel According to Silence. Now the S-um, too, made sense: it was simply a flattened Silentium. Can one speak about silence without destroying it? Can one comment on what…. Well, in a word, book killed book—with a single blow—and I won’t describe how my person-theme’s manuscript burned. Let’s just say it burned like….

There is so much in this passage to comment on. The marks the student finds in the Bible are not written with pen or pencil, but with a fingernail, evidence of a reader’s thoughts but these thoughts remain both unspoken and unwritten. All these moments when Jesus does not speak or refuses to speak force the reader to wonder why. Would answering the questions force Jesus to reveal too much? Does he not know the answers? Does he fear the way his audience might respond to them? Is silence simply the best answer available?

These questions plague the members of The Letter Killers Club throughout the novel and add up to a decent plot, if you ask me. But it’s a plot you’ll have to look for in the margins at times.

I thought it was worth the effort.

It’s been five years since I first ran this review on my old blog, Ready When You Are, C.B. Along the way, I had forgotten all about it. But it does sound good. Sounds like something I would like.

Advertisements Rate this:Share this: