Through the first half of 1942, American servicemen began to disembark en masse in Liverpool, paving the way for the build-up of forces that would eventually provide sufficient muscle to liberate North Africa, Italy and Occupied Europe. A significant number of Americans were already in Britain, however, having volunteered to fly with the Royal Air Force (just as they had in World War 1), whether it be under their own flag or adopting Canadian citizenship for the purpose.

Initially the call-to-arms had been made by Charles Sweeny, a wealthy businessman living in London, who took it upon himself to recruit American citizens to fight as a US volunteer detachment in the French Air Force, echoing the Lafayette Escadrille of WW1. When France collapsed under German invasion in May 1940, a dozen of Sweeny’s volunteers made their way to Britain, where they would be joined by 6,700 applicants from across the USA seeking to join the RCAF or RAF.

As a result of this recruitment drive, there were sufficient American pilots to form the three ‘Eagle’ squadrons of the RAF between September 1940 and July 1941 – these being nos. 71, 121 and 133. With the arrival of the US Army Air Force in strength, however, these units were due to be transferred back to American control and renamed the 334th, 335th and 336th squadrons of the 4th Fighter Group USAAF; their battle-hardened pilots intended to provide a finishing school for the eager recruits flowing across the Atlantic.

A month before the transfer took place, 133 Squadron was re-equipped with the new and top-secret Spitfire Mk.IX, featuring a two-stage supercharger to give better performance above 20,000 feet and provide a much-needed answer to the Focke-Wulf 190. Not all of the pilots were thrilled about becoming repatriated – not least the commanding officer, Squadron Leader Carroll McColpin, who repeatedly delayed and fudged his transfer until the last possible moment on 25 September. He was replaced by a temporary unit leader, Flight Lieutenant Gordon Bettrell, who found his new command somewhat unhappy about the situation.

As the unit had been declared operational on the Spitfire Mk.IX it was decided that 133 Squadron should give the type its operational debut the following day: 26 September 1942. On paper it looked like a relatively straightforward job of escorting American B-17 Flying Fortresses on a raid over the French town of Morlaix.

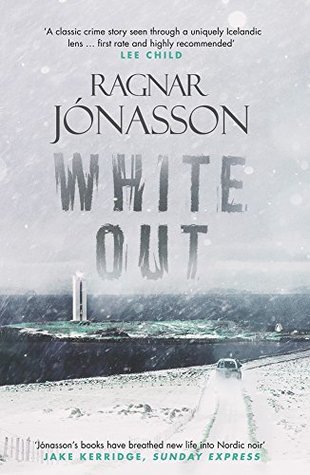

A Spitfire Mk.IX

A total of 14 Spitfire Mk.IXs shuttled down to RAF Bolt Head near Salcombe in Devon in readiness, of which only 12 were eventually required for the mission. One pilot from each flight – Ervin ‘Dusty’ Miller and Don ‘Buckeye’ Gentile – were ordered to remain on the ground. They were rather put-out by this news, having been keen to see how their new Spitfires would perform against the FW190s, but dutifully watched their squadron take off into low cloud. They were:

A Flight

F/Lt E.G. Brettell ES 313

P/O L.T. Ryerson BS 275

P/O W.H. Baker BS 446

P/O D.D. Smith BS 137

P/O G.B. Sperry BR 638

P/O G.G. Wright BS 138

B Flight

F/Lt M. E. Jackson BS 279

P/O R. E. Smith BS 447

P/O C.A. Cook BR 640

P/O R.N. Beaty BS 148

P/O G.H. Middleton BS 301

P/O G.P. Neville BS 140

Gentile and Miller waited. Then they waited some more. Eventually they heard approaching aircraft but these proved to be Spitfire Mk.Vs of 401 Squadron RCAF, which were also deployed on the mission. They were almost out of fuel and had seen neither the Fortresses or the Mk.IXs in the impenetrable cloud. Very clearly, something had gone disastrously wrong.

Word reached Bolt Head that one of the Eagle Squadron Spitfires had crash-landed on the coast just a few miles away. This turned out to be the only one of the 12 machines ever seen again.

The official squadron diary recorded: The 12 aircraft took off with 401 to make a rendezvous with the Fortresses in mid-channel at a point approximately half-way between Bolthead and Morlaix. It is not yet clear as to what exactly happened but some of the Fortresses were seen after our aircraft had been flying for 45 minutes. The pilot of one aircraft (P/O Beaty) alone returned from this operation and owing to petrol shortage crash landed in a small field near Kingsbridge, Devon. From his account and what he overheard on the R/T it seems probable that the rest of the Squadron force landed on the Island of Ouissant or on the French mainland.

It transpired that this was a rather optimistic view of the outcome. Following a strenuous board of inquiry, it became clear that 133 Squadron had never broken free of the cloud and was thus unaware of the fact that the north-easterly wind was blowing at 100 knots instead of the predicted 35. The increase in wind speed had been recorded but not communicated effectively to the squadrons. With no reference points to call upon, the flight leader, Flight Lieutenant Brettell, called for directions home and received a heading back to base from Morlaix – rather than from where he actually was.

The Fortresses were equally lost and equally far off course. When they broke free of the cloud they found themselves over the Pyrenees. They turned around and slogged back to Britain being more grateful for the cloud cover than on their outbound leg.

Meanwhile, having followed the prescribed heading for what was deemed the correct amount of time, Brettell closed up the formation and they dropped out of the cloud to see what they all assumed was the British coast. While looking for landmarks, the squadron passed over a large town – and immediately found themselves in a barrage of anti-aircraft fire that destroyed one Spitfire and damaged several others just before the defending FW190s swept in to savage them.

They had in fact made their way to the Germans’ prized port of Brest, one of the most heavily defended areas of the French coast. German sources reported all 12 of the Spitfires were shot down – although there were only 11 as the sole 133 Squadron Spitfire to get away, that of Pilot Officer Bob Beatty, had turned back early after suffering a misfire. Beatty made landfall in Devon by luck alone after gliding in to the coast when its fuel ran out, where it crashed near the village of Kingsbridge.

One other airman, Pilot Officer Robert Smith, made it back to Britain on foot after passing through France and into Spain undetected. Six pilots were killed in action and eventually four were taken POW. On 29 March 1944, Gordon Brettell was one of the officers involved in The Great Escape – he was later recaptured and summarily executed.

The element of surprise that was hoped for the Spitfire Mk.IX had been lost, as well as some of the most valuable combat experience available to the fledgling USAAF. Three days after the Brest raid, 133 Squadron transferred to American command with a compliment of earlier Spitfire Mk.Vbs (pictured top) and, following the board of inquiry, those ground controllers and met. officers who were responsible for the mission found themselves posted to the worst available hellholes in the Far East and North Africa as penance for their sins.

The USAAF continued to operate Spitfires on bomber escort duties for a number of months but R.J. Mitchell’s masterpiece was by design a short-range interceptor rather than a long-range escort fighter for offensive missions. On each occasion the Spitfire pilots were forced to watch German fighters circling until their own fuel became critical and they were forced to turn away… at which point the Germans would wade into the bombers without interference. This was a situation that would only change with the arrival of the P-47 Thunderbolt.

Advertisements Share this: