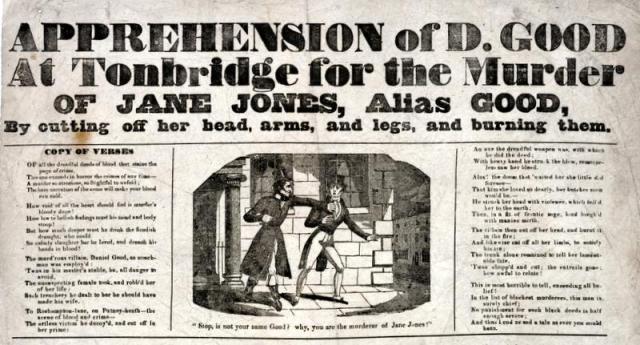

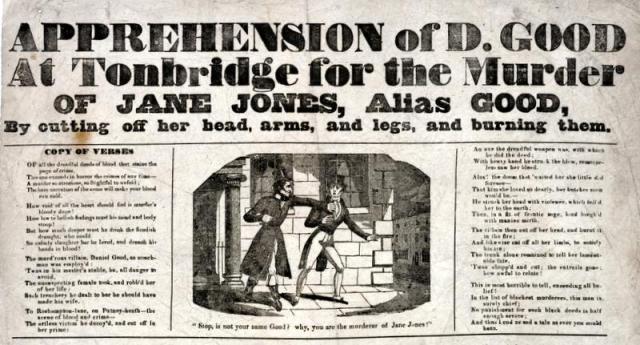

Despite the horror of the murder described above, please be assured my intention is not to re-visit such a barbarous crime merely for the sake of it – but rather to briefly tell the story of why that first word ‘APPREHENSION’ was so very significant for the future direction of London’s Metropolitan Police these one hundred and seventy-five years later.

However you will still need a ‘tasteless horror alert,’ not necessarily for the dismembered body parts, but for the incredibly crass behaviour of members of the public.

The month is April, the year is 1842 and the place is the hamlet of Roehampton on the rural outskirts of London.

So quickly banish your twenty-first century image of a highly populated suburb in London’s southwest in exchange for a tiny hamlet which, by definition, is smaller than a village. Everybody knows everybody.

Secrets are difficult to keep, privacy is a valuable commodity – and a certain coachman – Daniel Good aged 42, did have a terrible secret.

Now, that secret would no doubt have stayed that way had he not so foolishly stolen a pair of trousers from a pawnbrokers shop.

It was Wednesday, April 6th and Wandsworth police constable William Gardiner was sent to investigate the theft and all local fingers had been pointed at Daniel Good.

Gardiner visited the stable where Good worked, finding him with no difficulty and told him he had come to take him into custody for stealing a pair of black trousers from Mr. Collingbourn the local pawnbroker.

Now all should have been ended there for such a simple misdemeanor but from this straightforward encounter were to come vast reverberations for the future operation of London’s police force and grave concerns for distasteful displays of public behaviour and, oh yes – a brutal murder of a pregnant woman!

Now Daniel Good did not contest the fact he had taken the trousers, his reply was “Yes, I bought a pair of breeches off Mr. Collingbourn, and I did not pay him for them.” He pulled out his money purse and said to the police officer, “You can take the money to him.”

This was not an option, Good was arrested, but before being taken to Wandsworth police station, PC Gardiner wanted the stolen trousers to take as well.

Good did not cooperate and Gardiner made him stay while he searched the stables. By this time, Daniel Good’s little boy around 10 years old, had wandered in – he was also named Daniel, and was accompanied by the stable boy – a teenager called Speed.

Gardiner told Speed to watch the prisoner while he searched the stable stalls. Good wanted to leave for custody at Wandsworth and was clearly uncomfortable at PC Gardiner’s intentions to search the stable.

Houghton the gardener arrived and joined in the discussion and they all went into the stable for the search, whilst Good protested he just wanted to go to Wandsworth and get it sorted.

Good then walked in and moved a truss or two of hay immediately alerting PC Gardiner to his possible hiding place.

Gardiner soon discovered a piece of flesh, saying, “What is this? This is a goose?

Good then fled and locked all four of them in the stable. They tried to open the door but failed, so went back to look again at the flesh that had been found. The next scene is best described in P.C Gardiner’s legal testimony:

“I moved the remainder of the hay off, and thought it was a pig. I found it was the trunk of a female, the body. It was laying on its abdomen with the back uppermost – Speed turned it over – I had no difficulty then in discerning that it was a woman – the arms were cut off at the shoulders, and the legs cut off at the upper part of the thigh; the head severed from the body at the lower part of the neck and the thigh bone was taken right off at the hip – it was quite gone – the belly was cut open, and the bowels taken out – I then went to the door and succeeded in breaking out. The head and all the four limbs were gone.”

Now here we have the horrendous murder of a female victim; a named and recognizable suspect and lots of witnesses, including the suspect’s son, to Good’s erratic behaviour and flight from the law. All that is needed now is the identification of the victim and Daniel Good’s apprehension on suspicion of murder – but it was this latter ambition that was to cause the police so much anguish, i.e. the tracking and arrest of what the media was to call the ‘Roehampton Monster.’

But first, what of the general public and their reaction to the reports quickly circulating in the newspapers and broadsides?

Of course there was concern about the escape of the ‘Roehampton Monster’ but also a great deal of curiosity for people to see the scene where the body parts were discovered.

Additional information steadily found its way into the newspapers and broadsides, including the name of the victim and that the murderer had attempted to set fire to the body parts but failed and there was the suspicion by the surgeon’s assistant, Alfred Allen, that the woman had been pregnant based on the appearance of her nipples as nothing else remained to fully confirm it. The murdered woman was Jane Jones also known as Jane Sparks as well as having claim as a common-law spouse under the name, Jane Good.

Tasteless horror alert!

It became clear that morbid curiosity got the better of many people who could make their way to the stable site at Roehampton, hoping to get a glimpse of the murder scene and the body parts. Under the direction of the Coroner, the remains of Jane Jones had been taken into safe-keeping by a local constable for Roehampton and kept at his premises.

However, they were soon directed to be returned to the stable and replaced where they were originally discovered so as to form a grisly viewing opportunity for visitors to the site during the course of that same week-end.

The Times newspaper reported the following:

“On Sunday morning, from an early hour, vehicles of every description, from the aristocratic carriage to the costermonger’s cart, were seen wending their way towards the scene of the awful tragedy” (The Times, April 12th 1842 p.7.)

They went on to comment that:

“No-one was refused admission to view the disgusting exhibition. Amongst those who did so were, we regret to state, numerous females, some of whom would, we doubt not, aspire to be considered respectable women; who nevertheless, glutted their curiosity in beholding the mutilated remains of one who had borne the stamp, feature and sex of themselves. The police on duty outside the premises did, we understand, use their endeavours to put a stop to so glaring a breach of public decency, but the person in whose charge the body was declared said that he had the Coroner’s permission, and expressed his readiness to admit the public if they continued to arrive until 12 o’clock at night.” (The Times, April 12th 1842 p.7.)

So while the newspapers, especially The Times, became more and more outraged at the decline in public decency, the same newspaper also began to turn on the Metropolitan Police and their inability to capture this monster and so began a day-by-day attack on their incompetence in tracking down Daniel Good – ‘The Roehampton Monster.’

The Commissioners of Police offered a £100 reward, which soon increased to £150 when no progress was being made and on April 13th, The Times, claimed,

“The murderer is still in the heart of the metropolis.” (p.14.)

Soon they got even tougher;

The Times: April 15th – “The retreat of the murderer has not yet been discovered, and that excitement that pervades all minds suffers no abatement, but, on the contrary, increases as the chances lessen of the police being able to capture a man of such an atrocious and fiendish character. There is a feeling generally expressed, and we are sorry to say that it is one of unmitigated indignation against the police authorities for not using such diligence as must have had, under the circumstances, the effect of placing the monster in custody. We do hope for the sake of upholding the credit and confidence which have hitherto liberally bestowed by the public upon the metropolitan police, that they will make up for past dilatoriness by speedily bringing the murder to justice.” (page 6.)

The very next day, the pressure was increased, and the Coroner was reported as saying of Jane Jones’s body parts, “The remains must be kept above ground as long as possible and that police now have charge of the remains.”

Media pressure continued:

The Times April 16th “Nine days have now elapsed…..surely the public have a right to expect better things from the metropolitan police a force so great in numerical strength and maintained at so heavy cost to the country…….if the police suffer this man to escape, the will inflict upon themselves indelible disgrace, and the public will be led to suspect that there is something wrong in its government.” (page 6.)

Stories circulated about Daniel Good being a monster at age 13 when he reportedly killed a horse by ripping its tongue out. He was a convicted thief and had spent time in prison – so why were the police so incompetent?

It was The Times report of April 18th that finally produced a palpable sigh of relief from the battered and beleaguered London police.

The Times, April 18th Apprehension of the Murderer.

“The inhuman monster, Daniel Good, whose perpetration of a murder as foul and unnatural as any recorded in the annals of crime, and whose escape for so long a period from the hands of justice have occupied so large a portion of public attention is now in safe custody in Maidstone Gaol.” (page 5.)

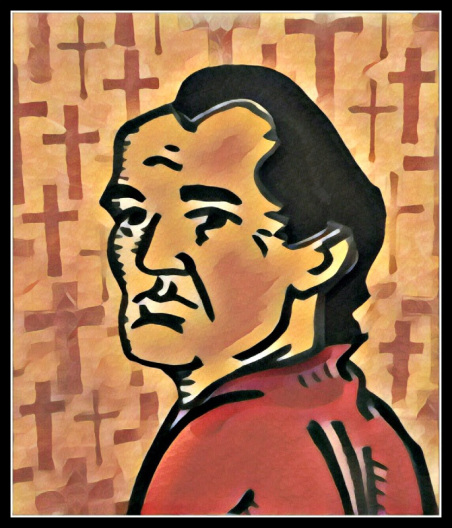

So – the broadside illustration that began this piece was the most significant by signalling the end of ten long days of frantic searching by a confused and ill-equipped police force that had foolishly let go of its specialist detective department, as it was called, when they disbanded the Bow Street Runners in 1839 and created this new, sparkling Metropolitan Police Force.

Devoid of the informers and sneaks that used to be paid by the Bow Street system in the ‘old days’ their concerns to end this so-called corruption, had lost them their network of detection and this taught them they desperately needed another. But it took another 36 years to really make it work and so on April 6th 1878 – ironically, the same date the dismembered body of Jane Jones alias Good was discovered in the stable by PC William Gardiner, The Times announced:

“From Monday next – April 8th – the whole of the detective establishment will form under one body under the directors of criminal investigations.” The Times, April 6th 1878 (page 11)

Only then was the real Criminal Investigation Department (CID) born.

Suffice it to say that Daniel Good was found guilty and hanged on May 24th at 8am outside Newgate Prison in front of an appreciative audience of thousands, some paying upwards of £15 for a ‘seat.’ The Times again:

“All the houses opposite the prison had been let to sight-seeking lovers at an enormous price. In several instances the whole of the casements had been taken out and raised seats erected for their accommodation.” The Times, May 25th 1842 page 8)

Right up to the end, Good denied murder and when asked by the priest, “Are you prepared to go into the next world?” Good replied, “I never took a life; may the Lord receive me into the gates of heaven. I never took a life.”

He most certainly did take two lives, but in a perverse way, he also forced improvements in policing and detective work so as to ensure that future ‘monsters’ like him are more likely to be apprehended sooner.

Advertisements

Share this:

Despite the horror of the murder described above, please be assured my intention is not to re-visit such a barbarous crime merely for the sake of it – but rather to briefly tell the story of why that first word ‘APPREHENSION’ was so very significant for the future direction of London’s Metropolitan Police these one hundred and seventy-five years later.

However you will still need a ‘tasteless horror alert,’ not necessarily for the dismembered body parts, but for the incredibly crass behaviour of members of the public.

The month is April, the year is 1842 and the place is the hamlet of Roehampton on the rural outskirts of London.

So quickly banish your twenty-first century image of a highly populated suburb in London’s southwest in exchange for a tiny hamlet which, by definition, is smaller than a village. Everybody knows everybody.

Secrets are difficult to keep, privacy is a valuable commodity – and a certain coachman – Daniel Good aged 42, did have a terrible secret.

Now, that secret would no doubt have stayed that way had he not so foolishly stolen a pair of trousers from a pawnbrokers shop.

It was Wednesday, April 6th and Wandsworth police constable William Gardiner was sent to investigate the theft and all local fingers had been pointed at Daniel Good.

Gardiner visited the stable where Good worked, finding him with no difficulty and told him he had come to take him into custody for stealing a pair of black trousers from Mr. Collingbourn the local pawnbroker.

Now all should have been ended there for such a simple misdemeanor but from this straightforward encounter were to come vast reverberations for the future operation of London’s police force and grave concerns for distasteful displays of public behaviour and, oh yes – a brutal murder of a pregnant woman!

Now Daniel Good did not contest the fact he had taken the trousers, his reply was “Yes, I bought a pair of breeches off Mr. Collingbourn, and I did not pay him for them.” He pulled out his money purse and said to the police officer, “You can take the money to him.”

This was not an option, Good was arrested, but before being taken to Wandsworth police station, PC Gardiner wanted the stolen trousers to take as well.

Good did not cooperate and Gardiner made him stay while he searched the stables. By this time, Daniel Good’s little boy around 10 years old, had wandered in – he was also named Daniel, and was accompanied by the stable boy – a teenager called Speed.

Gardiner told Speed to watch the prisoner while he searched the stable stalls. Good wanted to leave for custody at Wandsworth and was clearly uncomfortable at PC Gardiner’s intentions to search the stable.

Houghton the gardener arrived and joined in the discussion and they all went into the stable for the search, whilst Good protested he just wanted to go to Wandsworth and get it sorted.

Good then walked in and moved a truss or two of hay immediately alerting PC Gardiner to his possible hiding place.

Gardiner soon discovered a piece of flesh, saying, “What is this? This is a goose?

Good then fled and locked all four of them in the stable. They tried to open the door but failed, so went back to look again at the flesh that had been found. The next scene is best described in P.C Gardiner’s legal testimony:

“I moved the remainder of the hay off, and thought it was a pig. I found it was the trunk of a female, the body. It was laying on its abdomen with the back uppermost – Speed turned it over – I had no difficulty then in discerning that it was a woman – the arms were cut off at the shoulders, and the legs cut off at the upper part of the thigh; the head severed from the body at the lower part of the neck and the thigh bone was taken right off at the hip – it was quite gone – the belly was cut open, and the bowels taken out – I then went to the door and succeeded in breaking out. The head and all the four limbs were gone.”

Now here we have the horrendous murder of a female victim; a named and recognizable suspect and lots of witnesses, including the suspect’s son, to Good’s erratic behaviour and flight from the law. All that is needed now is the identification of the victim and Daniel Good’s apprehension on suspicion of murder – but it was this latter ambition that was to cause the police so much anguish, i.e. the tracking and arrest of what the media was to call the ‘Roehampton Monster.’

But first, what of the general public and their reaction to the reports quickly circulating in the newspapers and broadsides?

Of course there was concern about the escape of the ‘Roehampton Monster’ but also a great deal of curiosity for people to see the scene where the body parts were discovered.

Additional information steadily found its way into the newspapers and broadsides, including the name of the victim and that the murderer had attempted to set fire to the body parts but failed and there was the suspicion by the surgeon’s assistant, Alfred Allen, that the woman had been pregnant based on the appearance of her nipples as nothing else remained to fully confirm it. The murdered woman was Jane Jones also known as Jane Sparks as well as having claim as a common-law spouse under the name, Jane Good.

Tasteless horror alert!

It became clear that morbid curiosity got the better of many people who could make their way to the stable site at Roehampton, hoping to get a glimpse of the murder scene and the body parts. Under the direction of the Coroner, the remains of Jane Jones had been taken into safe-keeping by a local constable for Roehampton and kept at his premises.

However, they were soon directed to be returned to the stable and replaced where they were originally discovered so as to form a grisly viewing opportunity for visitors to the site during the course of that same week-end.

The Times newspaper reported the following:

“On Sunday morning, from an early hour, vehicles of every description, from the aristocratic carriage to the costermonger’s cart, were seen wending their way towards the scene of the awful tragedy” (The Times, April 12th 1842 p.7.)

They went on to comment that:

“No-one was refused admission to view the disgusting exhibition. Amongst those who did so were, we regret to state, numerous females, some of whom would, we doubt not, aspire to be considered respectable women; who nevertheless, glutted their curiosity in beholding the mutilated remains of one who had borne the stamp, feature and sex of themselves. The police on duty outside the premises did, we understand, use their endeavours to put a stop to so glaring a breach of public decency, but the person in whose charge the body was declared said that he had the Coroner’s permission, and expressed his readiness to admit the public if they continued to arrive until 12 o’clock at night.” (The Times, April 12th 1842 p.7.)

So while the newspapers, especially The Times, became more and more outraged at the decline in public decency, the same newspaper also began to turn on the Metropolitan Police and their inability to capture this monster and so began a day-by-day attack on their incompetence in tracking down Daniel Good – ‘The Roehampton Monster.’

The Commissioners of Police offered a £100 reward, which soon increased to £150 when no progress was being made and on April 13th, The Times, claimed,

“The murderer is still in the heart of the metropolis.” (p.14.)

Soon they got even tougher;

The Times: April 15th – “The retreat of the murderer has not yet been discovered, and that excitement that pervades all minds suffers no abatement, but, on the contrary, increases as the chances lessen of the police being able to capture a man of such an atrocious and fiendish character. There is a feeling generally expressed, and we are sorry to say that it is one of unmitigated indignation against the police authorities for not using such diligence as must have had, under the circumstances, the effect of placing the monster in custody. We do hope for the sake of upholding the credit and confidence which have hitherto liberally bestowed by the public upon the metropolitan police, that they will make up for past dilatoriness by speedily bringing the murder to justice.” (page 6.)

The very next day, the pressure was increased, and the Coroner was reported as saying of Jane Jones’s body parts, “The remains must be kept above ground as long as possible and that police now have charge of the remains.”

Media pressure continued:

The Times April 16th “Nine days have now elapsed…..surely the public have a right to expect better things from the metropolitan police a force so great in numerical strength and maintained at so heavy cost to the country…….if the police suffer this man to escape, the will inflict upon themselves indelible disgrace, and the public will be led to suspect that there is something wrong in its government.” (page 6.)

Stories circulated about Daniel Good being a monster at age 13 when he reportedly killed a horse by ripping its tongue out. He was a convicted thief and had spent time in prison – so why were the police so incompetent?

It was The Times report of April 18th that finally produced a palpable sigh of relief from the battered and beleaguered London police.

The Times, April 18th Apprehension of the Murderer.

“The inhuman monster, Daniel Good, whose perpetration of a murder as foul and unnatural as any recorded in the annals of crime, and whose escape for so long a period from the hands of justice have occupied so large a portion of public attention is now in safe custody in Maidstone Gaol.” (page 5.)

So – the broadside illustration that began this piece was the most significant by signalling the end of ten long days of frantic searching by a confused and ill-equipped police force that had foolishly let go of its specialist detective department, as it was called, when they disbanded the Bow Street Runners in 1839 and created this new, sparkling Metropolitan Police Force.

Devoid of the informers and sneaks that used to be paid by the Bow Street system in the ‘old days’ their concerns to end this so-called corruption, had lost them their network of detection and this taught them they desperately needed another. But it took another 36 years to really make it work and so on April 6th 1878 – ironically, the same date the dismembered body of Jane Jones alias Good was discovered in the stable by PC William Gardiner, The Times announced:

“From Monday next – April 8th – the whole of the detective establishment will form under one body under the directors of criminal investigations.” The Times, April 6th 1878 (page 11)

Only then was the real Criminal Investigation Department (CID) born.

Suffice it to say that Daniel Good was found guilty and hanged on May 24th at 8am outside Newgate Prison in front of an appreciative audience of thousands, some paying upwards of £15 for a ‘seat.’ The Times again:

“All the houses opposite the prison had been let to sight-seeking lovers at an enormous price. In several instances the whole of the casements had been taken out and raised seats erected for their accommodation.” The Times, May 25th 1842 page 8)

Right up to the end, Good denied murder and when asked by the priest, “Are you prepared to go into the next world?” Good replied, “I never took a life; may the Lord receive me into the gates of heaven. I never took a life.”

He most certainly did take two lives, but in a perverse way, he also forced improvements in policing and detective work so as to ensure that future ‘monsters’ like him are more likely to be apprehended sooner.

Advertisements

Share this:The Roehampton Monster, morbid curiosity and the Metropolitan Police.

Despite the horror of the murder described above, please be assured my intention is not to re-visit such a barbarous crime merely for the sake of it – but rather to briefly tell the story of why that first word ‘APPREHENSION’ was so very significant for the future direction of London’s Metropolitan Police these one hundred and seventy-five years later.

However you will still need a ‘tasteless horror alert,’ not necessarily for the dismembered body parts, but for the incredibly crass behaviour of members of the public.

The month is April, the year is 1842 and the place is the hamlet of Roehampton on the rural outskirts of London.

So quickly banish your twenty-first century image of a highly populated suburb in London’s southwest in exchange for a tiny hamlet which, by definition, is smaller than a village. Everybody knows everybody.

Secrets are difficult to keep, privacy is a valuable commodity – and a certain coachman – Daniel Good aged 42, did have a terrible secret.

Now, that secret would no doubt have stayed that way had he not so foolishly stolen a pair of trousers from a pawnbrokers shop.

It was Wednesday, April 6th and Wandsworth police constable William Gardiner was sent to investigate the theft and all local fingers had been pointed at Daniel Good.

Gardiner visited the stable where Good worked, finding him with no difficulty and told him he had come to take him into custody for stealing a pair of black trousers from Mr. Collingbourn the local pawnbroker.

Now all should have been ended there for such a simple misdemeanor but from this straightforward encounter were to come vast reverberations for the future operation of London’s police force and grave concerns for distasteful displays of public behaviour and, oh yes – a brutal murder of a pregnant woman!

Now Daniel Good did not contest the fact he had taken the trousers, his reply was “Yes, I bought a pair of breeches off Mr. Collingbourn, and I did not pay him for them.” He pulled out his money purse and said to the police officer, “You can take the money to him.”

This was not an option, Good was arrested, but before being taken to Wandsworth police station, PC Gardiner wanted the stolen trousers to take as well.

Good did not cooperate and Gardiner made him stay while he searched the stables. By this time, Daniel Good’s little boy around 10 years old, had wandered in – he was also named Daniel, and was accompanied by the stable boy – a teenager called Speed.

Gardiner told Speed to watch the prisoner while he searched the stable stalls. Good wanted to leave for custody at Wandsworth and was clearly uncomfortable at PC Gardiner’s intentions to search the stable.

Houghton the gardener arrived and joined in the discussion and they all went into the stable for the search, whilst Good protested he just wanted to go to Wandsworth and get it sorted.

Good then walked in and moved a truss or two of hay immediately alerting PC Gardiner to his possible hiding place.

Gardiner soon discovered a piece of flesh, saying, “What is this? This is a goose?

Good then fled and locked all four of them in the stable. They tried to open the door but failed, so went back to look again at the flesh that had been found. The next scene is best described in P.C Gardiner’s legal testimony:

“I moved the remainder of the hay off, and thought it was a pig. I found it was the trunk of a female, the body. It was laying on its abdomen with the back uppermost – Speed turned it over – I had no difficulty then in discerning that it was a woman – the arms were cut off at the shoulders, and the legs cut off at the upper part of the thigh; the head severed from the body at the lower part of the neck and the thigh bone was taken right off at the hip – it was quite gone – the belly was cut open, and the bowels taken out – I then went to the door and succeeded in breaking out. The head and all the four limbs were gone.”

Now here we have the horrendous murder of a female victim; a named and recognizable suspect and lots of witnesses, including the suspect’s son, to Good’s erratic behaviour and flight from the law. All that is needed now is the identification of the victim and Daniel Good’s apprehension on suspicion of murder – but it was this latter ambition that was to cause the police so much anguish, i.e. the tracking and arrest of what the media was to call the ‘Roehampton Monster.’

But first, what of the general public and their reaction to the reports quickly circulating in the newspapers and broadsides?

Of course there was concern about the escape of the ‘Roehampton Monster’ but also a great deal of curiosity for people to see the scene where the body parts were discovered.

Additional information steadily found its way into the newspapers and broadsides, including the name of the victim and that the murderer had attempted to set fire to the body parts but failed and there was the suspicion by the surgeon’s assistant, Alfred Allen, that the woman had been pregnant based on the appearance of her nipples as nothing else remained to fully confirm it. The murdered woman was Jane Jones also known as Jane Sparks as well as having claim as a common-law spouse under the name, Jane Good.

Tasteless horror alert!

It became clear that morbid curiosity got the better of many people who could make their way to the stable site at Roehampton, hoping to get a glimpse of the murder scene and the body parts. Under the direction of the Coroner, the remains of Jane Jones had been taken into safe-keeping by a local constable for Roehampton and kept at his premises.

However, they were soon directed to be returned to the stable and replaced where they were originally discovered so as to form a grisly viewing opportunity for visitors to the site during the course of that same week-end.

The Times newspaper reported the following:

“On Sunday morning, from an early hour, vehicles of every description, from the aristocratic carriage to the costermonger’s cart, were seen wending their way towards the scene of the awful tragedy” (The Times, April 12th 1842 p.7.)

They went on to comment that:

“No-one was refused admission to view the disgusting exhibition. Amongst those who did so were, we regret to state, numerous females, some of whom would, we doubt not, aspire to be considered respectable women; who nevertheless, glutted their curiosity in beholding the mutilated remains of one who had borne the stamp, feature and sex of themselves. The police on duty outside the premises did, we understand, use their endeavours to put a stop to so glaring a breach of public decency, but the person in whose charge the body was declared said that he had the Coroner’s permission, and expressed his readiness to admit the public if they continued to arrive until 12 o’clock at night.” (The Times, April 12th 1842 p.7.)

So while the newspapers, especially The Times, became more and more outraged at the decline in public decency, the same newspaper also began to turn on the Metropolitan Police and their inability to capture this monster and so began a day-by-day attack on their incompetence in tracking down Daniel Good – ‘The Roehampton Monster.’

The Commissioners of Police offered a £100 reward, which soon increased to £150 when no progress was being made and on April 13th, The Times, claimed,

“The murderer is still in the heart of the metropolis.” (p.14.)

Soon they got even tougher;

The Times: April 15th – “The retreat of the murderer has not yet been discovered, and that excitement that pervades all minds suffers no abatement, but, on the contrary, increases as the chances lessen of the police being able to capture a man of such an atrocious and fiendish character. There is a feeling generally expressed, and we are sorry to say that it is one of unmitigated indignation against the police authorities for not using such diligence as must have had, under the circumstances, the effect of placing the monster in custody. We do hope for the sake of upholding the credit and confidence which have hitherto liberally bestowed by the public upon the metropolitan police, that they will make up for past dilatoriness by speedily bringing the murder to justice.” (page 6.)

The very next day, the pressure was increased, and the Coroner was reported as saying of Jane Jones’s body parts, “The remains must be kept above ground as long as possible and that police now have charge of the remains.”

Media pressure continued:

The Times April 16th “Nine days have now elapsed…..surely the public have a right to expect better things from the metropolitan police a force so great in numerical strength and maintained at so heavy cost to the country…….if the police suffer this man to escape, the will inflict upon themselves indelible disgrace, and the public will be led to suspect that there is something wrong in its government.” (page 6.)

Stories circulated about Daniel Good being a monster at age 13 when he reportedly killed a horse by ripping its tongue out. He was a convicted thief and had spent time in prison – so why were the police so incompetent?

It was The Times report of April 18th that finally produced a palpable sigh of relief from the battered and beleaguered London police.

The Times, April 18th Apprehension of the Murderer.

“The inhuman monster, Daniel Good, whose perpetration of a murder as foul and unnatural as any recorded in the annals of crime, and whose escape for so long a period from the hands of justice have occupied so large a portion of public attention is now in safe custody in Maidstone Gaol.” (page 5.)

So – the broadside illustration that began this piece was the most significant by signalling the end of ten long days of frantic searching by a confused and ill-equipped police force that had foolishly let go of its specialist detective department, as it was called, when they disbanded the Bow Street Runners in 1839 and created this new, sparkling Metropolitan Police Force.

Devoid of the informers and sneaks that used to be paid by the Bow Street system in the ‘old days’ their concerns to end this so-called corruption, had lost them their network of detection and this taught them they desperately needed another. But it took another 36 years to really make it work and so on April 6th 1878 – ironically, the same date the dismembered body of Jane Jones alias Good was discovered in the stable by PC William Gardiner, The Times announced:

“From Monday next – April 8th – the whole of the detective establishment will form under one body under the directors of criminal investigations.” The Times, April 6th 1878 (page 11)

Only then was the real Criminal Investigation Department (CID) born.

Suffice it to say that Daniel Good was found guilty and hanged on May 24th at 8am outside Newgate Prison in front of an appreciative audience of thousands, some paying upwards of £15 for a ‘seat.’ The Times again:

“All the houses opposite the prison had been let to sight-seeking lovers at an enormous price. In several instances the whole of the casements had been taken out and raised seats erected for their accommodation.” The Times, May 25th 1842 page 8)

Right up to the end, Good denied murder and when asked by the priest, “Are you prepared to go into the next world?” Good replied, “I never took a life; may the Lord receive me into the gates of heaven. I never took a life.”

He most certainly did take two lives, but in a perverse way, he also forced improvements in policing and detective work so as to ensure that future ‘monsters’ like him are more likely to be apprehended sooner.

Advertisements

Share this:

Despite the horror of the murder described above, please be assured my intention is not to re-visit such a barbarous crime merely for the sake of it – but rather to briefly tell the story of why that first word ‘APPREHENSION’ was so very significant for the future direction of London’s Metropolitan Police these one hundred and seventy-five years later.

However you will still need a ‘tasteless horror alert,’ not necessarily for the dismembered body parts, but for the incredibly crass behaviour of members of the public.

The month is April, the year is 1842 and the place is the hamlet of Roehampton on the rural outskirts of London.

So quickly banish your twenty-first century image of a highly populated suburb in London’s southwest in exchange for a tiny hamlet which, by definition, is smaller than a village. Everybody knows everybody.

Secrets are difficult to keep, privacy is a valuable commodity – and a certain coachman – Daniel Good aged 42, did have a terrible secret.

Now, that secret would no doubt have stayed that way had he not so foolishly stolen a pair of trousers from a pawnbrokers shop.

It was Wednesday, April 6th and Wandsworth police constable William Gardiner was sent to investigate the theft and all local fingers had been pointed at Daniel Good.

Gardiner visited the stable where Good worked, finding him with no difficulty and told him he had come to take him into custody for stealing a pair of black trousers from Mr. Collingbourn the local pawnbroker.

Now all should have been ended there for such a simple misdemeanor but from this straightforward encounter were to come vast reverberations for the future operation of London’s police force and grave concerns for distasteful displays of public behaviour and, oh yes – a brutal murder of a pregnant woman!

Now Daniel Good did not contest the fact he had taken the trousers, his reply was “Yes, I bought a pair of breeches off Mr. Collingbourn, and I did not pay him for them.” He pulled out his money purse and said to the police officer, “You can take the money to him.”

This was not an option, Good was arrested, but before being taken to Wandsworth police station, PC Gardiner wanted the stolen trousers to take as well.

Good did not cooperate and Gardiner made him stay while he searched the stables. By this time, Daniel Good’s little boy around 10 years old, had wandered in – he was also named Daniel, and was accompanied by the stable boy – a teenager called Speed.

Gardiner told Speed to watch the prisoner while he searched the stable stalls. Good wanted to leave for custody at Wandsworth and was clearly uncomfortable at PC Gardiner’s intentions to search the stable.

Houghton the gardener arrived and joined in the discussion and they all went into the stable for the search, whilst Good protested he just wanted to go to Wandsworth and get it sorted.

Good then walked in and moved a truss or two of hay immediately alerting PC Gardiner to his possible hiding place.

Gardiner soon discovered a piece of flesh, saying, “What is this? This is a goose?

Good then fled and locked all four of them in the stable. They tried to open the door but failed, so went back to look again at the flesh that had been found. The next scene is best described in P.C Gardiner’s legal testimony:

“I moved the remainder of the hay off, and thought it was a pig. I found it was the trunk of a female, the body. It was laying on its abdomen with the back uppermost – Speed turned it over – I had no difficulty then in discerning that it was a woman – the arms were cut off at the shoulders, and the legs cut off at the upper part of the thigh; the head severed from the body at the lower part of the neck and the thigh bone was taken right off at the hip – it was quite gone – the belly was cut open, and the bowels taken out – I then went to the door and succeeded in breaking out. The head and all the four limbs were gone.”

Now here we have the horrendous murder of a female victim; a named and recognizable suspect and lots of witnesses, including the suspect’s son, to Good’s erratic behaviour and flight from the law. All that is needed now is the identification of the victim and Daniel Good’s apprehension on suspicion of murder – but it was this latter ambition that was to cause the police so much anguish, i.e. the tracking and arrest of what the media was to call the ‘Roehampton Monster.’

But first, what of the general public and their reaction to the reports quickly circulating in the newspapers and broadsides?

Of course there was concern about the escape of the ‘Roehampton Monster’ but also a great deal of curiosity for people to see the scene where the body parts were discovered.

Additional information steadily found its way into the newspapers and broadsides, including the name of the victim and that the murderer had attempted to set fire to the body parts but failed and there was the suspicion by the surgeon’s assistant, Alfred Allen, that the woman had been pregnant based on the appearance of her nipples as nothing else remained to fully confirm it. The murdered woman was Jane Jones also known as Jane Sparks as well as having claim as a common-law spouse under the name, Jane Good.

Tasteless horror alert!

It became clear that morbid curiosity got the better of many people who could make their way to the stable site at Roehampton, hoping to get a glimpse of the murder scene and the body parts. Under the direction of the Coroner, the remains of Jane Jones had been taken into safe-keeping by a local constable for Roehampton and kept at his premises.

However, they were soon directed to be returned to the stable and replaced where they were originally discovered so as to form a grisly viewing opportunity for visitors to the site during the course of that same week-end.

The Times newspaper reported the following:

“On Sunday morning, from an early hour, vehicles of every description, from the aristocratic carriage to the costermonger’s cart, were seen wending their way towards the scene of the awful tragedy” (The Times, April 12th 1842 p.7.)

They went on to comment that:

“No-one was refused admission to view the disgusting exhibition. Amongst those who did so were, we regret to state, numerous females, some of whom would, we doubt not, aspire to be considered respectable women; who nevertheless, glutted their curiosity in beholding the mutilated remains of one who had borne the stamp, feature and sex of themselves. The police on duty outside the premises did, we understand, use their endeavours to put a stop to so glaring a breach of public decency, but the person in whose charge the body was declared said that he had the Coroner’s permission, and expressed his readiness to admit the public if they continued to arrive until 12 o’clock at night.” (The Times, April 12th 1842 p.7.)

So while the newspapers, especially The Times, became more and more outraged at the decline in public decency, the same newspaper also began to turn on the Metropolitan Police and their inability to capture this monster and so began a day-by-day attack on their incompetence in tracking down Daniel Good – ‘The Roehampton Monster.’

The Commissioners of Police offered a £100 reward, which soon increased to £150 when no progress was being made and on April 13th, The Times, claimed,

“The murderer is still in the heart of the metropolis.” (p.14.)

Soon they got even tougher;

The Times: April 15th – “The retreat of the murderer has not yet been discovered, and that excitement that pervades all minds suffers no abatement, but, on the contrary, increases as the chances lessen of the police being able to capture a man of such an atrocious and fiendish character. There is a feeling generally expressed, and we are sorry to say that it is one of unmitigated indignation against the police authorities for not using such diligence as must have had, under the circumstances, the effect of placing the monster in custody. We do hope for the sake of upholding the credit and confidence which have hitherto liberally bestowed by the public upon the metropolitan police, that they will make up for past dilatoriness by speedily bringing the murder to justice.” (page 6.)

The very next day, the pressure was increased, and the Coroner was reported as saying of Jane Jones’s body parts, “The remains must be kept above ground as long as possible and that police now have charge of the remains.”

Media pressure continued:

The Times April 16th “Nine days have now elapsed…..surely the public have a right to expect better things from the metropolitan police a force so great in numerical strength and maintained at so heavy cost to the country…….if the police suffer this man to escape, the will inflict upon themselves indelible disgrace, and the public will be led to suspect that there is something wrong in its government.” (page 6.)

Stories circulated about Daniel Good being a monster at age 13 when he reportedly killed a horse by ripping its tongue out. He was a convicted thief and had spent time in prison – so why were the police so incompetent?

It was The Times report of April 18th that finally produced a palpable sigh of relief from the battered and beleaguered London police.

The Times, April 18th Apprehension of the Murderer.

“The inhuman monster, Daniel Good, whose perpetration of a murder as foul and unnatural as any recorded in the annals of crime, and whose escape for so long a period from the hands of justice have occupied so large a portion of public attention is now in safe custody in Maidstone Gaol.” (page 5.)

So – the broadside illustration that began this piece was the most significant by signalling the end of ten long days of frantic searching by a confused and ill-equipped police force that had foolishly let go of its specialist detective department, as it was called, when they disbanded the Bow Street Runners in 1839 and created this new, sparkling Metropolitan Police Force.

Devoid of the informers and sneaks that used to be paid by the Bow Street system in the ‘old days’ their concerns to end this so-called corruption, had lost them their network of detection and this taught them they desperately needed another. But it took another 36 years to really make it work and so on April 6th 1878 – ironically, the same date the dismembered body of Jane Jones alias Good was discovered in the stable by PC William Gardiner, The Times announced:

“From Monday next – April 8th – the whole of the detective establishment will form under one body under the directors of criminal investigations.” The Times, April 6th 1878 (page 11)

Only then was the real Criminal Investigation Department (CID) born.

Suffice it to say that Daniel Good was found guilty and hanged on May 24th at 8am outside Newgate Prison in front of an appreciative audience of thousands, some paying upwards of £15 for a ‘seat.’ The Times again:

“All the houses opposite the prison had been let to sight-seeking lovers at an enormous price. In several instances the whole of the casements had been taken out and raised seats erected for their accommodation.” The Times, May 25th 1842 page 8)

Right up to the end, Good denied murder and when asked by the priest, “Are you prepared to go into the next world?” Good replied, “I never took a life; may the Lord receive me into the gates of heaven. I never took a life.”

He most certainly did take two lives, but in a perverse way, he also forced improvements in policing and detective work so as to ensure that future ‘monsters’ like him are more likely to be apprehended sooner.

Advertisements

Share this:

Related articles

Related books