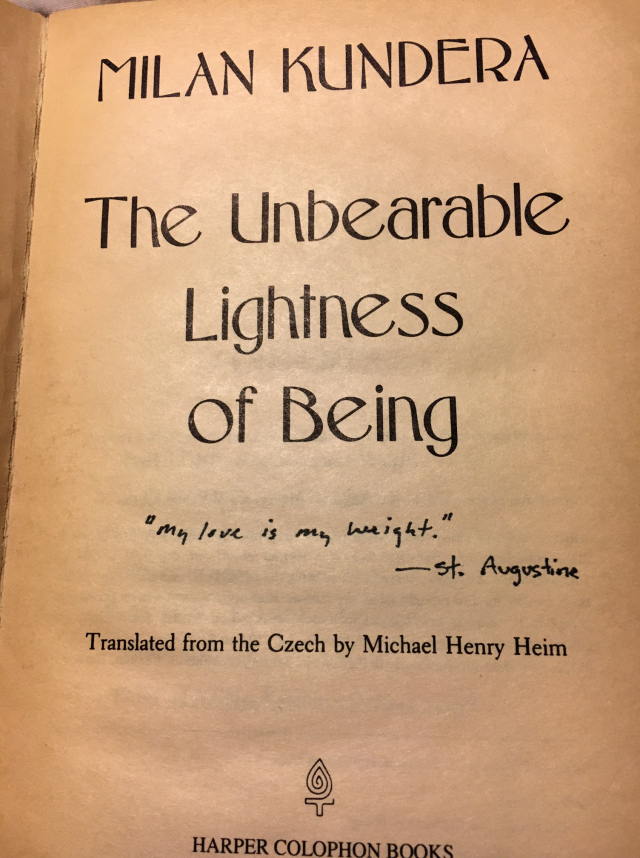

At a recent library sale, I paid twenty-five cents for a new paperback copy of Milan Kundera’s novel, The Unbearable Lightness of Being to replace the dog-eared, yellowing copy I’ve had for 35 years. Still, I find it hard to part with the old artifact. I know the book’s paper is too brittle to survive another reading, but this is the very book I connected with as a 25-year-old graduate student. And it captured the central struggle of the first half of my life: the choice between a painful lightness and freedom in single life and the weight of commitment and what came to be the joy and grounding of a happy marriage and family. I lived in the state of “unbearable lightness” for more than 15 years, not marrying until 40, not becoming a father until I was 42 years old. Not so uncommon in my generation, but a long wait nonetheless.

At a recent library sale, I paid twenty-five cents for a new paperback copy of Milan Kundera’s novel, The Unbearable Lightness of Being to replace the dog-eared, yellowing copy I’ve had for 35 years. Still, I find it hard to part with the old artifact. I know the book’s paper is too brittle to survive another reading, but this is the very book I connected with as a 25-year-old graduate student. And it captured the central struggle of the first half of my life: the choice between a painful lightness and freedom in single life and the weight of commitment and what came to be the joy and grounding of a happy marriage and family. I lived in the state of “unbearable lightness” for more than 15 years, not marrying until 40, not becoming a father until I was 42 years old. Not so uncommon in my generation, but a long wait nonetheless.

Kundera’s novel describes the journey of a man, a doctor, and a promiscuous one at that, quite different my young timid self, but caught in the same purgatory of “lightness”—this delusion that life could somehow be easier without what Kundera calls “the heaviest of burdens,” which is “simultaneously . . . life’s most intense fulfillment.” He captured this for me in a way I clearly understood but still resisted:

The heavier the burden, the closer our lives come to the earth, the more real and truthful they become. Conversely, the absolute absence of a burden causes man to be lighter than air, to soar into the heights, take leave of the earth and his earthly being, and become only half real, his movements as free as they are insignificant. What then shall we choose? Weight or lightness?

These words spoke directly to my young self in 1985. I took what Kundera said as a call to arms, if you will. I even jotted on the title page of my hammered paperback an epigraph from St. Augustine: “My love is my weight.” Yet I didn’t marry my wife, Maura, until March 24, 2000. For more than 15 years, I was a single man adrift. It was not wasted time. In fact, I would like to think I lived well: I worked hard, loved my immediate family, traveled, threw myself into volunteer service, writing and music. Most important, I pursued one romantic relationship after another, falling in love, feeling the acute pain of it many times—convinced I was willing to take on whatever weight life required of me. Looking back, I’m not so sure. Part of me must have known I was floating, refusing to enter a truer life. I held something back and clung to “unbearable lightness,” part of me believing I was more free and safe from damage.

Now, when I let go of this old book about to fall apart in my hands, I feel both a familiar longing for the old lightness and a relief beyond words that I escaped it, perhaps only by a hair’s breadth, and finally embraced the sweet weight of love, marriage, parenthood—all that now makes me alive in the world, at last more substance than intention.

Share this:- Share