photo by Ashim D’Silva via Unsplash

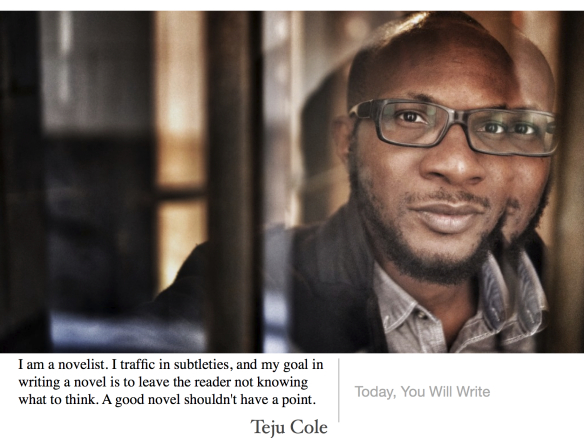

You would not think that a full-scale recapitulation of Ecclesiastes would make a great bestseller. Vanity, vanity, all is vanity! This human thing is an exercise of unknowing. I know that there is nothing better than that they should eat, drink, and experience pleasure in their hard work. This is the philosophy of the Preacher.

But George Saunders is a fascinating variety of weird. In Tenth of December, his 2013 short story collection, he found a hundred ways to trouble the surface of contemporary life and it was funny and edgy, drawing on spirituality and our anxieties about the technological age and what it’s doing to our sense of self. Flannery O’Connor meets Gary Shteyngart is how I described it.

George Saunders is a fascinating variety of weird.

In Lincoln in the Bardo, Saunders’ first novel, he’s still working with an outrageous premise—that the ghostly residents of a certain DC cemetery are spying on President Lincoln as he visits the grave of his recently-dead son—and he’s still impossible to put down. This is the work of an author using all of his gifts, most especially his prodigious curiosity, to wonder at the meaning of eternal things.

The historical nugget around which the story is built is a scant mention of Lincoln’s late-night visits in 1862 to the crypt where his young son, Willie, was interred. Saunders uses a mountain of historical research and some added fictional accounts to paint a portrait of Lincoln that is full of contradictions. At times the historical voices can’t even agree on Lincoln’s eye color, much less his political policies. And the weight of these judgments by his contemporaries weighs on the president, whose own inner voice in this novel is full of the awareness, not only of the death in his own life, but of the many deaths he feels responsible for in the nascent war.

The historical nugget around which the story is built is a scant mention of Lincoln’s late-night visits in 1862 to the crypt where his young son, Willie, was interred. Saunders uses a mountain of historical research and some added fictional accounts to paint a portrait of Lincoln that is full of contradictions. At times the historical voices can’t even agree on Lincoln’s eye color, much less his political policies. And the weight of these judgments by his contemporaries weighs on the president, whose own inner voice in this novel is full of the awareness, not only of the death in his own life, but of the many deaths he feels responsible for in the nascent war.

Lincoln is interesting, but the real characters in this story are the dead who are lingering in the graveyard. The bardo is a concept borrowed from Buddhism in which disembodied souls are caught in an intermediate, waiting state following death. The residents here can’t quite come to grips with where they are. They refer to the cemetery as a “hospital-yard” and their coffins as “sick-boxes” and they chastise each other for believing that their earthly stories are at an end. When “angels” invade to encourage their compatriots to “move on,” they see it as a threat, even though its clear that this is the way to peace.

The residents here can’t quite come to grips with where they are. They refer to the cemetery as a “hospital-yard” and their coffins as “sick-boxes” and they chastise each other for believing that their earthly stories are at an end.

This is like nothing so much as C.S. Lewis’ vision of the after-life in The Great Divorce in which souls that could not discover God and peace in life are still struggling after death. As in that book, the appearance of the dead is sometimes fantastically altered to reflect their inner struggles. Those who can’t let go of their distorting preoccupations are condemned to continue suffering them.

There are some problems here. Saunders handling of the black characters seems a little tacked on and the way he suggests that Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation was the result of possession by one of them is too clever by half. But the overall effect is…well, haunting.

When Lincoln finally moves to leave his boy, his parting words are not profound, but ring with all the pain and beauty of grief: “Love, love, I know what you are.”

This book is an affirmation of life and an honest admission that the world is greater than we can know. Like Psalm 131, the perspective veers toward a studied contentment: “Lord, my heart isn’t proud; my eyes aren’t conceited. I don’t get involved with things too great or wonderful for me. No. But I have calmed and quieted myself like a weaned child on its mother.”

Or as Roger Bevins, III, regretful about his suicide, puts it at the end (in not too much of a spoiler, I hope):

Advertisements Share this:“None of it was real; nothing was real. Everything was real; inconceivably real, infinitely dear. These and all things started as nothing, latent within a vast energy-broth, but then we named them, and loved them, and in this way, brought them forth. And now we must lose them.

“I send this out to you, dear friends, before I go, in this instantaneous thought-burst, from a place where time slows and then stops and we may live forever in a single instant. Goodbye goodbye good-”