Matthew Finn: From Mother

There are lots of accounts in photography of intimately close relationships. Of course there are, since you could say simply that photography has become the ‘natural’ medium of affection. Every family album is affection congealed in physical form. Every photograph framed in silver then perched on a mantelpiece or a piano was an attempt to hold on to affection – even if only dutiful affection. Usually these worked in the absence of the person photographed; occasionally as some more ideal version of that person than the flawed daily one of wearied familiarity.

At this usual, simple level, the photography seems to play a relatively straightforward role. There was a relationship: this is what the people involved looked like when they were tidied up for the camera. But sometimes the photographs in some way are the relationship itself as distinct from a record of it.

Leigh Ledare; Mom with Mask, 1972. Leigh Ledare provides only an example among very many of the infinite complexity of tales which can be told or acted out in photographs.

No doubt Matthew Finn’s extraordinary set of pictures of his mother Jean fall into that category. They were made over a period of very many years, and the fact of the pictures — the need to make them, the act of making them, the results of making them — must have changed the relationship between them. She’s his mother; but she’s also performed for him the part of his mother. He’s her son; but he also acted the role of the photographer. Remember that in spite of the pictures, we actually know very little of their relationship. We know that together they acted out a version of it, and that version was for our consumption.

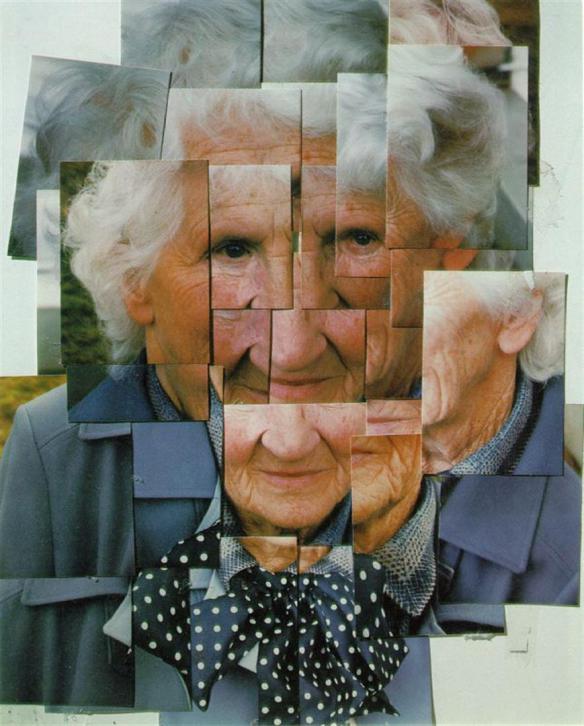

David Hockney; Mother, Yorkshire Moors, 1985

A number of years ago, David Hockney made one of the most tender of his ‘joiners’ as a portrait of his mother. The joiners were collages – multiple photographs which mimicked the flickering way the eye moves over and around a subject. Hockney wanted us to linger over the face of his mother as he had often done – and a single photograph would have been too easy to ‘get’ then dismiss as a single framed bit of information. So he borrowed from Cubism the habit of looking from several points of view at the same time. Hockney’s mother has three or four noses, three of four mouths; you see her head from the left and from the right. Yet none of that dodgy anatomy matters at all so long as you see her slowly. That turns your glance into a caress and so allows you to reproduce some of the caress of Hockney’s own way of looking at her, his eye travelling gently over the many surfaces of her face.

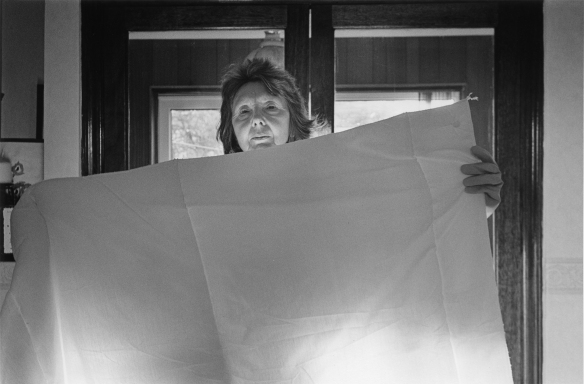

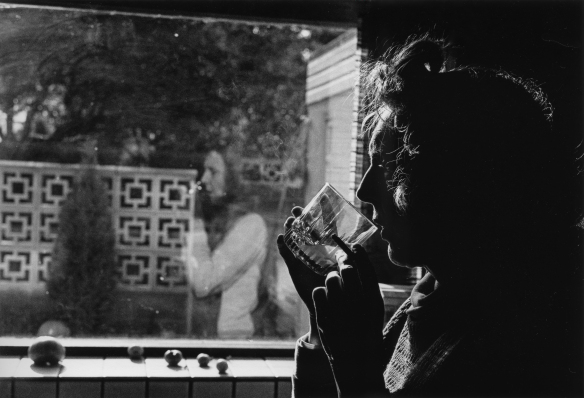

Matthew Finn; From Mother

Matthew Finn. From Mother.

There is a lot in that notion that affection takes time to record. Matthew Finn’s act of photography is moving partly because it took so very long. If so much photography has the throw-away quality we understand by the snapshot, then surely its opposite might be true: slowly made might imply great value. And slowly made might be an invitation to look slowly, too. Nicholas Nixon’s mesmerizing photographic project — The Brown Sisters, in which he photographed his wife and her sisters every year over a lifetime, and they age and change before our eyes like a flip book in slow motion — is another good example of the same thing. Matthew Finn’s mother ages and sickens through the photographs as she aged and sickened through time. Quite impossible simply to glance and go.

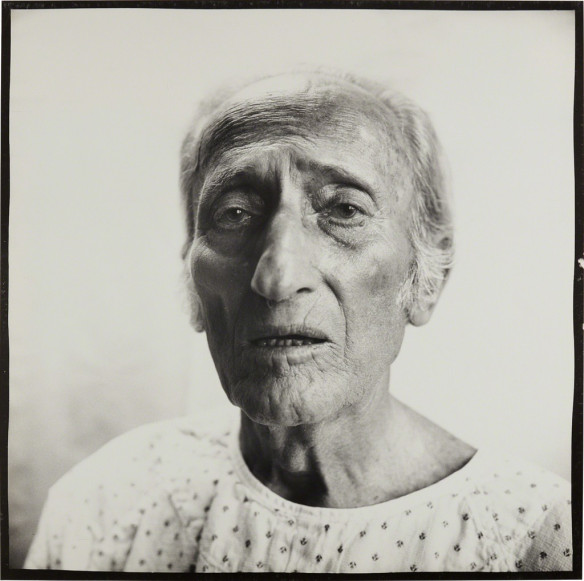

Richard Avedon; Jacob Israel Avedon, Sarasota, 1972

Photography is complicated. It’s by no means always just the slowness of the process which asks our attention. Richard Avedon made a monumental series of portraits of his father across the end of the 1960s and the opening of the 1970s. Jacob Israel Avedon goes from business attire to hospital gown as the series develops. His face becomes gaunt, his expression agonized like a medieval painting of a martyr. They’re simple pictures, close-to, no background, yet we can actually see the growing bond as the repeated performance took hold of them both. Avedon wrote with emotion of the experience of making them — in a way which is perhaps relevant to Matthew Finn:

“At first my father agreed to let me photograph him but I think after a while he began to want me to. He started to rely on it, as I did, because it was a way we had of forcing each other to recognize what we were. I photographed him many times during the last year of his life but I didn’t really look at the pictures until after he died.

They seem now, out of the context of those moments, completely independent of the experience of taking them. They exist on their own. Whatever happened between us was important to us but it is not important to the pictures. What is in them is self-contained and, in some strange way, free of us both.”

Forcing each other to recognize what we were, he said. It’s a beautiful phrase, and one which says a lot about the misunderstandings between children and their parents. Was Matthew Finn looking to recognize what his mother was? Was he allowing her — in a reversal of the usual power relations between parent and child — to express herself as a mother? Or was he trying to hold sand on a fork as time kept on sliding by? We don’t need to know.

Matthew Finn; From Mother

We don’t even know what to call this kind of photography. It has in it something of autobiography, of course; something of documentary; something even of performance or play. There used to be something called ‘concerned photography’, a phrase long out of fashion now. It tended towards social issues more than personal ones. Matthew Finn’s long collaboration with Jean is all of these things and none of them. Do we mind which category it falls under? All we can see is the intensity of his looking. He stared a long time like a hawk at his mother. And she never blinked back.

Mother, by Matthew Finn, was shown at Francesca Maffeo Galery in Essex. I wrote this little text to accompany the exhibtion, and both photographer and gallerist have been gracious enough to let me reprint it here. The book of the series has recently (2017) been published by Dewi Lewis with an essay by Elizabeth Edwards under the ISBN 978-1-911306-14-6

Advertisements Share this: