Previous essay about the first film.

Batman Returns is the bleakest meditation on sexual dysfunction in arrested adolescence ever to be licensed for a McDonald’s Happy Meal.Against all odds, Tim Burton had turned the first Batman into a character study about artistic ego and sexual competition, in the guise of an action film. When given total freedom for the sequel he turned what could’ve simply been Batman II: The Adventure Continues into a whirlwind tragicomedy of feminism, class struggle and kinky fetishism.

A generation was scarred. People HATE this movie. They roll their eyes and spout talking points about how it “wasn’t true to the comics,” how it was too weird or campy, how it was mean that Batman set a guy on fire. They say it was too much of a “Tim Burton movie.” But when did Tim Burton ever make another film this unsettling ever again? Even for a guy whose stock in trade is the macabre, Batman Returns brought out his most extreme bag of tricks.

It always strikes me how Burton correctly understood that comic book adventure is an outlet for the power trips and sexual frustrations of young egos, Batman in particular being their apotheosis with his goth-romantic aesthetic and oedipal origin story. The triangle of neuroses between Batman, The Joker and Vicki shifted in the sequel to a more blatantly orgiastic triangle of sexual hostility between The Bat, The Cat and The Penguin: social Darwinism played out amongst a trio of animal-people. In Daniel Waters, fresh from his previous film Heathers, about teenagers with psychotic egos, sexual dysfunctions and social hierarchies, he found the perfect writer to continue the first film’s subtext of adolescent angst disguised as superhero hijinks. Even more so than Batman ’89, which was about how different types of creative people (Bruce Wayne, Jack Napier) express their will to power, Returns is about how misfits try to define their identities to the world in a way that still gets them laid.

For probing even further into the most emotionally traumatic corners of Gotham City, Burton was not asked back to make a third Batman film. Maybe it would have been redundant. Movie trilogies are an overrated idea anyway; Return of the Jedi, Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome and Alien 3 all failed to outdo their first two chapters.

If you don’t believe me that Batman Returns is entirely about sexual frustration consider that the first person we see onscreen is Paul Reubens, in what was his first public role since being arrested for public masturbation in a porno theater. He and Burton were friends of course, but it was kind of a warning: On the surface this is light entertainment for kids, but…

I was six years old when my mom and dad sat down with me to watch the film on video. I had already seen Batman and though The Joker was sometimes intense and the violence occasionally a bit much, I was too entranced by the richness of the imagery to feel any lasting discomfort. Batman was good, The Joker was evil and as with the rest of my children’s entertainment, I could count on the former eventually vanquishing the latter. The story had a twisted tone, but was ultimately reassuring.

What happens in the first half hour of Batman Returns? Well, a mom and dad heartlessly attempt infanticide on their freak baby by throwing it into a river. Then an army of killer clowns attack a crowd of Christmas revelers. Then a monstrously deformed man pulls severed body parts from a bag, and that’s just the first 20 minutes. But we continued onward, my parents and I – sensitive people, my parents – I think they’d still be as disturbed by the film now as they were twenty-five years ago. We continued to the next scene, when an innocent woman is shoved out a window and survives only to suffer a nervous breakdown, and wreck her apartment in a psychotic rage. It was at that point I had to ask to be let off the carnival ride, and my mom hit the STOP button. Specifically, it was the shot of Michelle Pfeiffer stabbing her stuffed animals that broke me, I think because at that age I still anthropomorphized stuffed animals as living things. There’s an incineration of innocence earlier as well, when during the inexplicable evil circus attack on Christmas revelers a teddy bear is immolated by a Satanic fire-breather.

Imagine variations on that awkward incident being repeated with millions of small children all over America and you’ll begin to conceive how Batman Returns, remembered today in passing as a quirky 90s footnote was really quite infamous in its day. No movie intended for the widest of possible wide audiences, produced on such a large budget, will ever be allowed to be so gleefully misanthropic ever again, let alone a superhero movie. Suicide Squad, The Dark Knight, Deadpool – every so-called “edgy” and “adult” superhero movie has still held onto the pretense of some socially redeeming value, with some amiability towards the audience. Batman Returns, like Robocop and a handful of other exceptional fantasy-genre movies, has a purely whimsical relationship with you, the audience.

Because superhero movies are unequivocally the worst trend in movie history, it’s important to note how even three years after the runaway financial success of Batman they still were not a genre unto themselves, granting Tim Burton the leeway to go even deeper into how fucked up the whole Batman concept was. In the first film you were invited to fantasize about being the dark and mysterious Batman or the colorful and flamboyant Joker. This time around, to see oneself in Batman, Catwoman or The Penguin is only to recognize the sharp pangs of self-righteous, wounded anger. This is the real reason why so many people hate this film: it reflects back upon the viewer their emotional investment in the Batman mythos, with the merciless clarity of a full length mirror.

If you’re a well-adjusted person, it’s a sometimes baffling amusement. If you’re a fan of superheroes, which is to say not a well-adjusted person, it’s a breathtakingly strange angle on the spectacle of grown men and women play-acting these beloved childhood icons. For fans of modern superhero movies I imagine it’s harrowing, because those are the people who want, more than to be entertained, to be lied to and told that there is anything remotely good for their mind or soul about clinging onto these fantasies well into their adulthood.

The sexual conflict of Batman ’89 can be handily categorized into 1) an extroverted alpha battling 2) an introverted beta for possession of 3) a high-value alpha female. Batman Returns has a more thorough index of the mating spectrum, characterizing Batman, Catwoman, The Penguin and intermediary villain Max Shreck in more complex terms as each of them jockeys against one another to gain more social power.

Daniel Waters’ first creative writing was a column in his high school newspaper wherein he wrote stories about fellow classmates, which is kind of impossible to imagine being allowed today. I think it’s safe to assume this man who later wrote an unapologetic comedy about a high school’s mean girls being murdered could easily look out upon hhis high school and determine whom among them was a Bruce Wayne kind of guy, a Selina Kyle kind of girl, a Max Shreck or an Oswald Cobblepot. He projected the world of Batman through his prism of high school social politicking, which is especially painful for comic book geeks and another reason this film makes them uncomfortable to think about. High school hierarchy is a reflection of sexual marketplace value, and anyone observing the archetypal personalities within such cliques will notice thinner lines between some castes than others. Many roles are created by circumstance, rather than innate differences of character. Bruce Wayne, Selina Kyle and Oswald Cobblepot all have more in common than they know, even if they’re eating at different lunch tables.

For Bruce Wayne, things have changed a bit since the first film. Being the mysterious, brooding rich kid is no longer enough to compensate for his neurotic goofiness.

Batman is still the shy beta masking his withdrawn nature with material privilege. In one scene he slowly cruises the Batmobile around the city at night, not unlike a moody teenager driving at low speeds through their small town’s back roads, smoking clove cigarettes at 2am and listening to Unknown Pleasures. Incidentally, the one original pop song on the film’s soundtrack – as opposed to the sexually liberated Prince tunes of its predecessor – is a melancholy ballad by Siouxsie and the Banshees. Bruce has lost his hot blonde girlfriend, we learn, because she’d had enough of his weirdness. Or, “difficulty with duality.”

Bruce does have a new possibility for romantic love to match his own unbalanced psyche: the beta female Selina Kyle, turned alpha Catwoman after her psychotic break, an analogue to his own identity disorder coping mechanism. Catwoman had always been positioned as Batman’s love interest on the wrong side of the law throughout the years of the franchise, but giving her a pivotal, tragic transformation and thus common ground with Bruce Wayne was the film’s own inspired invention. Where Burton and Waters take this idea way beyond the limits of family entertainment is giving that transformation the full grindhouse exploitation film treatment. She’s Ms. 45 saying I Spit On Your Grave throughout Gotham’s Savage Streets, you macho men aren’t Death Proof after all. The attempted murder through a window is her symbolic rape at the hands of her boss, Max Shreck, who is as much a cartoon as his co-stars: a Marxist-Feminist caricature of a murderous misogynist capitalist. He’s so toxically masculine he’s literally dumping chemical waste into the sewers.

In turn, Catwoman herself is the epitome of those kamikaze avenging-angel grindhouse gals whose whole purpose is revenge against scummy men. The only other example around the same time of this b-movie character type going mainstream would’ve been the very popular but now forgotten Thelma and Louise, which had come out just the year before.

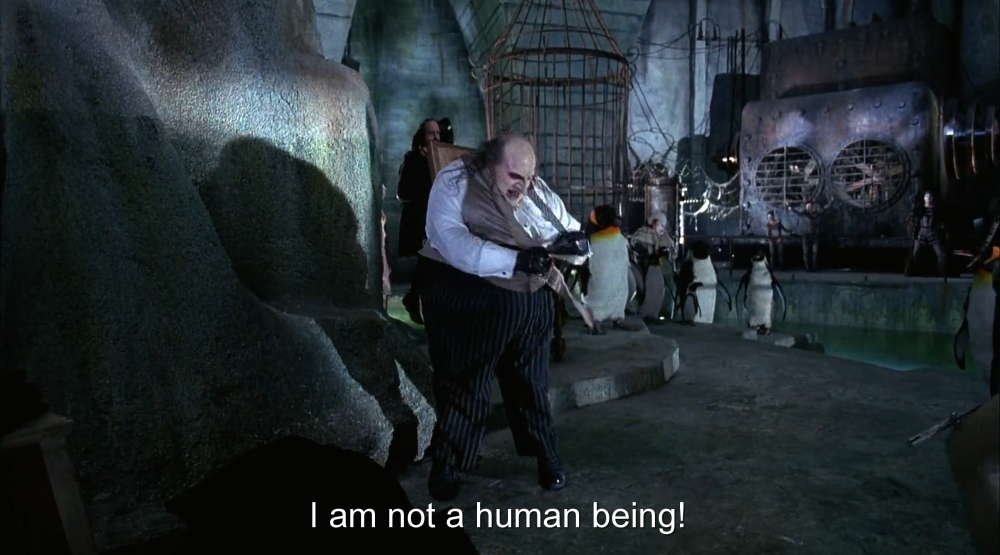

Unlike Vicki Vale, readily physically available to Bruce yet judged to be undeserving of his commitment, Selina Kyle never consummates her attraction to Bruce Wayne, nor Catwoman to Batman, despite these halves of their split personalities aligning so evenly. The only really perfect love is love that gets away.Last and least is Oswald Cobblepot, The Penguin, The untouchable low man on the social totem pole. The proverbial guy who couldn’t get some in a whorehouse if he were made of money. This film is arguably his story, more justifiably than the common criticism that the first Batman should’ve been called Joker.

At the height of Burton’s popularity as a director, fans reveled in the gallery of outsiders who populated his films. Unlike Edward Scissorhands, Penguin isn’t going to clean up nice. In Oswald Cobblepot you have the nadir of outsiders, a man with no attractive qualities who’s too bitter for redemption. Where Catwoman evokes sympathy, Penguin evokes pity, disgust and gallows-humor horror. The prologue establishes this when deformed baby Oswald, cruelly imprisoned in a cage, yanks a passing house cat through his bars for lunch. Is he a victim of prejudice, or an actual monster? Burton hedges his bets, the way Brian De Palma sneakily betrayed poor Carrie White by having her arm rise from the grave for the sake of one final scare. While they sympathize with him, Burton and Waters also find it hilarious imagining The Elephant Man as an unrepentant asshole.

The filmmakers ask us to go along with the conceit that, not content with the glamor of growing up a circus freak, the Penguin somehow formed a huge criminal gang comprised of fellow circus performers. This is where the limits of tolerance for Burton’s whimsy are really tested for the average viewer, pushing the already paper-thin boundaries of credibility from the first Batman that a bunch of professional criminals would agree to be an insane clown posse – now Batman’s opponents have gone from gangsters and thugs to organ grinders and stilt walkers. The only thing making it palatable is the uncanny visual spectacle of these creepy carnies running amok through a snow-covered metropolis at Christmastime. It’s still the film’s weakest element, and the first tentative step down the road of big budget campiness which would dead-end with Batman & Robin. If their seemingly arbitrary, enigmatic “Red Triangle” namesake has any meaning it may refer to the badge assigned for political prisoners in Nazi death camps – red triangles specifically, not the pink triangles better known for their homosexual designation. Carnies, subversives…you get what they might have been going for.

The story requires Penguin to have his Red Triangle Circus Gang together so he can leverage his power as a crime boss to blackmail Max Shreck into making him a celebrity. Apparently he seeks public redemption as an unfortunate soul cast aside by society, who can forgive the world for treating him inhumanely and reclaim his humanity, just like John Merrick – but it’s all a ruse. He never gives up being a crime boss, never forgives his parents, and by extension never forgives the people of Gotham for denigrating him as a freak in the first place.

Like so many lonely people with troubled pasts, Penguin doesn’t know what to do with acceptance once he gets it, especially since it wasn’t obtained through honest means. Waters’ script is particularly acidic in the scenes when Penguin plays on pity publicity like a harp from hell, expertly manipulating celebrity culture’s love of the downfall-and-rehabilitation narrative. This is the truth the socially alienated outsider must face when attempting to emerge from out of the darkness, that being a misfit does not in itself make one righteous.

Penguin’s switch flips from self-pity to violent rage at a moment’s notice, like the brutal common criminal who bashes your grandma’s head open for her purse, who then recites the refrain that it was a cold and uncaring world which reduced them to such desperate deeds. “You’re a well-respected monster, while I am, to date, not” says Oswald when first revealing himself to Max Shreck. This is the self-assessment of a man who has already redefined himself as a dangerous criminal; better that than a hapless freak. It’s funny to see Burton, renowned champion of the freaky misfit, indulging the revenge fantasy of the angry misfit.

Whereas the Joker’s villainy came from the creative person’s anarchic side, Penguin’s comes from a much grimmer place: the seething of a person who will never fit in anywhere.

Fleshing out the Penguin’s character to three dimensions, with plenty of room for identification with his pain, prefigured similar revisions of many Batman villains throughout the 90s. This was the beginning of post-modernism in superhero comics, the end-of-history no-more-bad-guys approach. Alan Moore created it with Watchmen and The Killing Joke and in a few short years it became cliché. This decade’s most famous Batman villain, Bane, was created in 1993 with (of course!) a torturous childhood origin story. Virtually every villain re-introduced on Batman: The Animated Series was given some kind of new sympathetic motivation for their criminal careers: cheated by corporate crookery, heartbroken over unrequited love, et cetera – society is to blame! Truly evil, or just victims of circumstance?

Burton takes a lot of critical drubbing to this day for radically elaborating upon The Penguin, but in his defense there wasn’t much of an interesting character there to start with – a top hat, some umbrellas, a fat gut and a height deficiency. Penguin’s future incarnations would forever be colored by Returns, it’s gotten to the point where just to keep apace with the franchise’s brand of emphasizing every villain’s otherness, his most recent iteration on the TV series Gotham is gay and has an unrequited crush on The Riddler. Perhaps some bright producer noticed the spate of headlines a few years ago about “gay penguins” rearing eggs together in captivity. The dandyish fashion sense certainly fits, and actor Robin Lord Taylor may or may not have been chosen for the role in part because of his real life homosexuality. It’s somewhat startling how LGBTQ groups haven’t given the show any flack, as the various details the show’s writers added to this modern Oswald Cobblepot are classically anti-gay: he’s a momma’s boy, obsequiously smarmy and prone to shrieking hysterics. His closest cinematic antecedent is basically Bruno Anthony from Strangers on a Train.

It was a short list in 1992 for actors who’d actually lived the Napoleonic rage of growing up a little man in a big, uncaring world. Danny DeVito is four feet, ten inches tall, which is as tall as you can grow and still be considered a dwarf according to the Little People of America. Tapping into a lifetime of short-man-syndrome, he’s mainlining that perfect casting which occurs when an actor’s natural persona can be fully exaggerated, like Jack Nicholson’s in the first film. But unlike Nicholson’s devilish clowning, DeVito instead expresses the raw, rabid anguish of being looked down on your whole life. Smaller kids do get bullied more. Robin Lord Taylor? Five-foot-six. I’m only 5’8” and when I was a kid, my parents moved to the Midwest where I was soon towered over by normal people, of healthy northern European stock – so I get it, believe me.

Bruce Wayne’s fellow freaks in Batman Returns are so much closer to himself than his photo-negative nemesis of The Joker that the most obvious parallel between him and Oswald Cobblepot could only be mentioned once in passing, because more than that would have it would have been pedantic: they were both rich kids orphaned at an early age.

As in the first film, Bruce stands as a figure of ethical nonconformity in contrast to his antagonist, but the nuances of the second film’s villains bifurcate viewers. Those who tend towards pity will see Penguin’s moral monstrosity as resulting from his misfortune of physical deformity, the failure of his parents to be kinder, and the loss of his material privilege which could have softened the blow. Others will point out what seems like his innate, incurable nastiness of character – look what he did to that poor cat! Bruce at least had Alfred to keep him on a straight path. The difference between being a traumatized outsider who makes good, and one who spirals into psychosis often just comes down to good parenting. If you’re bullied at school, a healthy home environment can provide shelter and solace. Neglected, ostracized children grow up depressed and neurotic at best, self-destructive criminals or standup comics at worst. Everyone knows or at least knows of a kid from their youth who didn’t make it, who offed themselves because they couldn’t take the regular abuse they were getting at home, at school or both.

Less dramatically but no less pitifully, many kids at the lower levels of youth’s social pecking order simply fade away as they grow old, into NEET life or isolated wage slavery, self-medicating through the years with weed, Internet pornography and video games. They were taught early on not to believe in themselves. My most disturbing personal example of this is an elementary school friend who was noticeably short of stature and by high school was regularly being chased by jocks into the bathroom stalls, basically replicating the “I am not an animal!” scene from The Elephant Man once a week. The last I heard of him, he was clinically obese and living in his mom’s basement. Short, fat, turning pale from dwelling underground, probably going bald by now. Maybe he eats a lot of fish, too.

There are other examples, of course. The closeted young gay man who attempts suicide, and survives only to fry his brains on narcotics. Young women who never fully recover from being sexually abused. Those who lost a parent when they were just a kid, and found out the hard way that such losses don’t turn you into a superhero. We all know people like this, and we all know that a lot of them don’t just “get over it.” Flipping the script on your victimization to become Batman or Catwoman is a compelling childish dream, but Batman Returns is uncomfortably honest about how its characters’ efforts to alleviate their suffering and powerlessness with vengeance can’t bring them peace, even in this fantasy comic book world.

Every Batman fan thinks The Joker is so cool, but which villain does the average Batman fan more closely resemble, The Joker or Oswald Cobblebot?Penguin’s quest to claim the lifetime of rich kid prestige he was denied, with interest, takes form in a conspiracy with Max Shreck to recall and replace the mayor of Gotham City with himself, using the Red Triangle Circus Gang for a series of false flag operations. Spiro Agnew, the Gulf of Tonkin and the Reichstag Fire are namechecked by Shreck, which I always remember when braindead fanboys shill for the allegedly clever political commentary of Christopher Nolan’s films. Batman Returns was produced and released against the backdrop of the 1992 presidential election, and Burton joked in public about how Oswald was an unholy amalgamation of the three major candidates – warmongering creep George H.W. Bush, lecherous pervert Bill Clinton and needle-nosed sideshow Ross Perot, who measured up at five-foot-five, nearly a foot less than his opponents and one inch shorter than Robin Lord Taylor.

When the film introduces Penguin’s political ploy, the baseness of his true motivations become abruptly, horribly clear as Burton and Waters hit us over the head with Oswald’s decades worth of sexual frustration erupting forth, after what had been, to this point, plausibly the somewhat touching story of an outcast child connecting with the outside world. As the grotesque “Penguin-man” visiting his parents’ gravestone and reclaiming his proper family name, he had the public’s sympathy. But sympathy is not attraction, and what man wants to be pitied rather than desired? Mulling over Shreck’s enticement to take over the mayor’s office, Oswald’s eye glitter darkly as the possibilities are listed: “The ear of the media…access to captains of industry…”

As the aphorism goes, politics is show business for ugly people. When you’re as ugly as the Penguin, only a career in show business or politics can earn you sexual currency and he’s already tried the freak tent. The glamour of high office successfully distracts him from his bloodlust against the normies, but only until Batman foils his scheme with a hot mic. Before then, there’s some pretty choice Waters-isms like “I could really get into this mayor stuff! It’s not about power, it’s about reaching out to people! Touching people! GROPING PEOPLE!”

Political history has no shortage of hideous men using their office and influence for prurient interests; a never-ending procession of dead mistresses, molested interns and underage prostitutes. The comparison to politics with show business surely has something to do with the high percentage of unattractive males eagerly cashing in their new acclaim and success for the long-denied attention of females. Instead of growing up they will forever be marking up revenge notches on their bedpost. There is a robotic sociopathy behind the eyes of many a public attention-seeker, who never stop hating those women who ignored them and sent them on their way to becoming a power-hungry social climber – excuse me, Public Servant – in the first place.

Hollywood, another aphorism goes, is just high school with money. And sometimes, when Carrie White has her Prom crown defiled, she burns down the school in retribution. Batman’s actions reveals the true motives behind Penguin’s aspirations: the least popular kid in school, the freak, desperately wants the other kids to like them while simultaneously hating their guts. It’s The Penguin as Elliot Rodger: if the hot girls don’t give me the sex I deserve then they’re still going to get fucked, by me, in a much messier way.

Some kids who don’t fit in withdraw into themselves. Some of them nurse grudges and remember names. Many well-adjusted adults can still remember the names of childhood bullies. After the Columbine shooting, my mom got a phone call from my junior high school because someone had noticed I’d been keeping a list of bullies I hated. Why was I even doing that? Was there any power in this hypothetical revenge list? I was just wallowing in anger.

Failing his mayoral bid, Penguin’s last stand against Gotham brings his destiny full circle as their freak show Moses – sent down the river as a baby, he’s going to fulfill his destiny by committing mass infanticide upon the city’s first born sons, from a list of names he’s compiled like some Maoist apparatchik (the Red Triangle Guard?) preparing for a purge. It’s during the scene when he announces this plot to his circus gang that Burton finally, mercifully winks to the audience at how messed up this grim faerie tale of a “superhero movie” has become, when a fat clown (played by Travis McKenna of the immortal Party Plane) politely interrupts his boss: “Uh, Penguin? I mean…killing sleeping children…isn’t that a little, uh…?”

To which Oswald shoots him. “No. It’s a LOT!”

And that’s what this movie was. It was a lot. For everyone.One of the forgotten nuggets of controversy amidst all the backlash around perversion and child endangerment came from the Jewish Anti-Defamation League, who saw in Penguin’s short stature, beak nose, love of raw fish and bloody Passover plot a live-action Nazi propaganda cartoon. All together, you have to admit that’s a bingo of stereotypes. There’s no shortage of cultural caché in the Jewish experience around feeling defined by your outsiderness that never quite lets you blend in seamlessly with the larger population, pining for greater acceptance that may never come. What Makes Oswald Run? A friend of mine once pointed out that my self-identified “nerd” qualities which drew the attention of bullies during adolescence were, basically, stereotypically Jewish traits – the neurotic intellectual whining, mostly. What you do wind up with in every sophisticated subculture is a kind of unavoidable antipathy towards broader society, and this attitude is alternately celebrated by Jews and gays in outsider hero-figures like Woody Allen or Oscar Wilde, who are also despised by gentiles and straights for that same subversive shit-stirring.

If Batman Returns’ Oswald Cobblepot is anti-semitic then Gotham’s is absolutely, flagrantly homophobic. What’s stunning is how imperceptibly these ugly stereotypes came to define the mainstream conceptions of this otherwise forgettable comic book villain. Even in an era obsessed with identity politics and geek bullshit, it wasn’t even newsworthy that the latest live action portrayal of The Penguin was gay and crushing on the fucking Riddler. The fans just said “yeah, it fits.”

As Oswald’s slaying-of-the-first-born commences he crashes Max Shreck’s costume ball, a gathering of the beautiful people. Effectively he’s shown up at his school prom with automatic weapons (albeit strapped to penguins) because the social capital which could compensate for his hideousness and get him laid is gone. Screaming to the Red Triangle gang that his name is not Oswald, it’s Penguin, ironically emancipates him from such animal concerns as copulation with fellow humans. Or at least, the substitution of one animal tactic (peacocking for attraction) with another important activity from the animal kingdom: slaughtering your enemies’ young in their nests.

Anticipating the plague of his own design, Penguin at last gets his Jack Napier-unto-Joker, come-to-Satan moment. His wait’ll they get a load of me grin. But his malevolent glee is short lived. Batman puts a stop to his dreams of Death-from-Above-1992 in a fraction of the time it took to ruin Joker’s parade balloon gas attack. Penguin’s death scene, unlike Joker’s grandiose swan dive, is a belly flop with protracted internal bleeding. We pause with Batman to observe a procession of penguins somberly push their master to his final resting place, the watery grave his parents always intended. This is how you know Burton really loves the gross little guy. When the first film sent off Joker, his dead eyes and frozen smile more or less broke the fourth wall to winked at the audience, vaguely recalling Nicholson’s photograph at the conclusion of The Shining, as if saying We sure had fun together, didn’t we folks? Penguin’s dead eyes betray nothing except the merciful end to a pathetic life.

Catwoman’s inclusion in Batman Returns had the exact opposite problem of the Penguin: there was already too much going on with her. Too many cultural connections between cats and women, too much sexual fetishism inherent in the costume, too many actresses playing Catwoman on the 60s TV show. So rather than taking the easy route of making her a sultry femme fatale, Waters and Burton reinvented her character as radically as they had Penguin’s, into a new kind of female antiheroine – one which hadn’t really existed before and is still being copied to this day.

Even people who loathe this film concede a respect for Catwoman. Her lack of current appreciation may also have less to do with the film’s reputation than today’s Tumblr feminists not yet being alive when the film was released and taking her influence for granted. Living in an age where every new pop culture event is weighed against competing political factions’ propaganda interests, it’s incredible that in 1992 a high profile feminist antihero was considered a trifle – it suggests the wymxn of the early 90s hadn’t yet figured out how political victories are secondary to cultural ones. At the time they probably said Oh great, we finally get a mainstream feminist antihero and she’s in a BATMAN MOVIE, who’s going to take that seriously? Flash forward twenty-five years to the release of a Wonder Woman film being hailed as the biggest advance since the 19th amendment. And capital-F Feminists don’t even really want a goody two-shoes like Wonder Woman, they want Selina Kyle raking a rapist across the face with her homemade claws.

Selina Kyle, bespectacled secretary bullied by her chauvinist boss, has a bad day one day. She’s victimized by street crime, her current boyfriend blows her off because his fragile male ego can’t handle her not letting him win at racquetball, and when she gets home from her boss’ murder attempt, the answering machine plays a sexist perfume robocall that finally triggers her into a frenzy of feminine object destruction – all those poor stuffed animals – plus a pink dollhouse. She sews a costume for her new alter-ego and sets out to avenge herself, and if Batman doesn’t like her breaking the law to do that, then that’s too bad for him.

For this new female archetype to emerge, she had to combine several factors which could really only be found in a comic book character like Catwoman. The key reason she heralded the end of one epoch, and the beginning of another which has not yet ended, is that aside from the rape-revenge trope Daniel Waters borrowed from exploitation / grindhouse films, he was also writing a character permitted by comic book logic to hold her own in combat against Batman – you know, the guy who ostensibly trained his whole life to be an ass-kicking vigilante.

The 80s was the last decade of cartoonishly hyper-masculine, borderline homoerotic machismo: Arnold Schwarzenegger, the WWF, Mr. T, Top Gun, He-Man, et cetera. The 90s were characterized by more sensitive, less muscular male action heroes: Will Smith and Keanu Reeves became the most popular leads of action movies increasingly focused on surreal special effects rather than fistfights or gun battles. Into this more fantastical, less masculine field of mainstream escapism emerged a new kind of character type following Catwoman’s example: Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Xena: Warrior Princess, Lara Croft – the female action fantasy heroine. By the early 2000s, Milla Jovovich had begun her long tenure of Resident Evil movies. Oscar-winning actress Angelina Jolie played the live action Lara Croft, and Uma Thurman culturally appropriated Bruce Lee’s outfit in Kill Bill. The archetype became codified – it’s so commonplace now that people forget it really started as a novelty, and Michelle Pfeiffer sits perched right at the axis of that innovation.

The big change was this: when the majority of action films are happening in a comic book reality, and CGI allows your actors to perform any conceivable physical feat, every woman is a potential Catwoman – backflipping her way across rooftops and high-kicking Batman off the side of a building. Technology made this masculinist-feminist fantasy possible on film.The illogic of Selina Kyle’s sudden and inexplicable prowess at karate is one of those drearily common criticisms leveled at Batman Returns by self-hating manchildren who demand the pretension of realism to enjoy their adolescent make-believe. Her new physical power is vaguely suggested to be of supernatural origin, as her lifeless body is apparently resurrected from the dead by a swarm of stray cats who emerge from the alleyway she landed in, after Max Shreck threw her from his building. The film further plays up the mythical connections to cats by having Selina refer to her nine lives, as she later miraculously survives being shot repeatedly at point blank. Cats have been associated with women ever since they were burned as witches’ familiars in the middle ages, and in doing so have transposed to women their mystical qualities. The first Batman fantasized that childhood trauma and a theatrical black costume could transform a quirky nerd into a powerful, imposing figure. In Returns, Bruce Wayne’s female analogue Selina Kyle endures violent death and upon her rebirth, crafts a theatrical black costume which gives form to her new, almost undead soul. It’s child’s fairytale logic, like the assumption of children that Superman’s ability to fly must come from wearing a cape.

Women don’t care about rational problems like “why is Selina Kyle able to fight Batman just by putting on her Catwoman costume.” Batman Returns gave them their own Batman; an introvert nerd girl who becomes an avenging warrior. One of these days I swear I’m just going to snap and kill my pig of boss if he calls me “sweetie” one more time. Selina Kyle’s moral ambiguity and ferocity is encapsulated in her first act as Catwoman: saving an innocent bystander from a mugging & potential rape, but then victim-blaming the woman for making it “So easy.”

What offset this abrasiveness was her her vendetta against the truly evil Max Shreck, and the extended pathos of her mental deterioration – as opposed to Bruce Wayne’s post-traumatic process of becoming Batman, which was best left to our imaginations. Carol J. Clover wrote that the horror film archetype of the terrorized woman who avenges herself arguably resonated so strongly with nerdy male horror film fans because they could project themselves into the physically smaller, frailer forms of young women, as opposed to the macho heroes of action/adventure films. Batman Returns posits Catwoman as the anarchic fantasy of repressed feminine id awoken from within a mousy wallflower – one who can be shamelessly lustful towards Batman himself. As the tagline to Carrie put it, If only they knew she had the power.

The terrible downside to Catwoman’s seismic impact on pop culture was that it mainstreamed another classic fetish of neurotic men, the hot chick who can kick your ass – the dominatrix.The scene where two bumbling department store security guards spot Catwoman and comment they “don’t know whether to open fire or fall in love,” just before she whips the guns from their hands with a one-liner about “you poor guys always confusing your pistols with your privates” has been copied in roughly every single action film with a female character ever since. As has the moment where after Batman knocks her down, she mewls “How could you? I’m a WOMAN!” only to sucker punch him in return. Mind you, there were plenty of female villains who fit this bill – Sam Hamm’s original script for Batman II would have cast Catwoman in the mold of a lethal, amoral nymphomaniac who makes knowing references to “discipline.” But in making Selina Kyle sympathetic, Dan Waters inadvertently opened the floodgates for these more morally ambiguous kinds of heroines and antiheroines.

Buffy, Xena, Lara Croft and all their descendants have a respectable number of female fans but this doesn’t change the fact most of them were created by men for a primarily male audience who get a thrill watching them perform their tough-girl shtick. More recent examples include Mark Millar’s Hit-Girl from Kick-Ass, Michonne from The Walking Dead or Rey from Star Wars. They run, they jump, they shoot, they punch, they barely have personalities beyond their capacity as human action figures – usually their only characterization is smirky sadism or determined stoicism. This vast majority of female fantasy heroines and antiheroines are written as either Manic Pixie Dream Girls with black belts, or Boss Ass Biches – from Harley Quinn to Kim Possible. And those are from the better examples, typically the quality is closer to the ladies of Charlie’s Angels or Underworld. An army of would-be Catwomen, masturbation effigies hawking the pop culture’s shallow fantasy of feminine empowerment through masculine violence.

The geek-culture-industrial-complex sells these pinups as strong women and their celebration by women betrays a dearth of genuine female heroism elsewhere in pop culture, plus a female population generally as infantilized by geek culture as their male counterparts. Undersexed men remain the primary purchasing audience of video games and superhero comics, as reliably as undersexed women are the primary purchasers of romance novels. Uma Thurman slices up bad guys with a katana and Daisy Ridley slices up bad guys with a light saber, but slicing up bad guys with phallic objects is still a young man’s daydream and putting those objects in women’s hands is just a extra spice. Women like it on a surface level because they like the idea of being able to fight five men at once, and thanks to movie magic they can see a woman who looks like Keira Knightley accomplish that feat.

This scam of commercialized comic book feminism has been going strong for more than a generation now. These women are absurdly competent, aesthetically pleasing and don’t the nerdbros just love feeling progressive for lusting after strong women. Most men do not fantasize about being rescued from a burning building by Supergirl, they fantasize about fucking her. Likewise, most women do not have martial arts or zombie apocalypse survival fantasies compared to the number who fantasize about being wooed by Edward Cullen, Mr. Grey or even Harry Potter. If you really want to see how audiences respond to the placement of women without sex appeal in traditionally male roles, check the profit margin on the 2016 version of Ghostbusters.

This development happened within the context of another insidious trend in mainstream pop culture of the 1990s, done well by Batman Returns before being vulgarized into a lazy default mode that’s lasted ever since: the co-opting of irony and resentment from the countercultural underground. I can’t tell you how dispiriting it was to grow up in the that decade feeling like an outsider, while simultaneously seeing this very slick aspirational corporate version of rebellion called Alternative Culture everywhere you looked in films, TV and music. Punk went pop, depression was aestheticized in music videos and every mall in America got a Hot Topic. Parodies of happy 1950s Americana became so commonplace that every time I see a modern variant of parodic gee-honey-I’m-home kitsch it still registers in my head as a 90s throwback. Kurt Cobain saw this acceleration from inside the system and did what I guess he felt he had to do, just so he wouldn’t have to see Trent Reznor receiving an Oscar twenty years later.

Similarly, I’m sure Daniel Waters didn’t mean to create a stereotype in his vision of Catwoman to be copied ad nauseum. He was probably more annoyed by Heathers being relentlessly imitated throughout the 90s in films like The Craft, Scream and Jawbreaker, until post-Columbine hysteria moved the direction of Hollywood’s teen product towards the safe violence of Superhero Movies. Look, I enjoyed a laugh with Wednesday Addams, Daria Morgendorffer and Marla from Fight Club as much as the next guy in those days. But in hindsight, what did we really have to be so smug and cynical about, in that post-Cold War, pre-War on Terror decade?

When Dan Waters wrote Heathers and Batman Returns he was indulging the dark fantasies of young rebels, with compassion but without sentimentality. He got there first. So did Tim Burton with Wynona Ryder’s character in Beetlejuice, who I think was the first real teenage goth character in a mainstream film, just a year before she’d star in Heathers. Selina Kyle’s Heathers moment, by the way, happens when she shows up at Max Shreck’s costume ball in fancy dress, planning to shoot him – Homecoming Queen’s Got a Gun – before Penguin beats her to the punch with a kidnapping. The film does have a High School Homecoming Queen cipher; an ill-fated model sneakily titled “The Ice Princess” whom the movie offhandedly derides as a bimbo before Penguin pushes her off a building (women can’t catch a break, or break a fall in this film.)

The still-timeliness of Batman Returns’ hostility is best embodied when Selina Kyle mocks Bruce Wayne for having dating a woman named “Vicki” in the previous film.

It’s spittle in the eye of the prior film, and the whole prior decade which venerated homecoming queen types like Kim Basinger as their most popular actresses. Pfeiffer’s shorter haircut isn’t arbitrary – they could have easily created a long-haired Catwoman; but lessening her hair volume reflected the upcoming trend away from traditional femininity throughout the 90s. The same year that Batman was released, in his review of The Fabulous Baker Boys Armond White railed against “the critical confusion of (Michelle Pfieffer’s) California cheerleader’s essence with acting” – but years later hailed her “post-feminist hellcat” version of Catwoman in comparison to a “one-note femme fatale” version portrayed by Anne Hathaway in The Dark Knight Rises.

They stick Batman with a love interest in every stupid movie, and Michelle Pfeiffer’s Catwoman is still the only one who ever made sense.Michelle Pfeiffer and Michael Keaton have chemistry together because both can play crazy, in and out of costume. Several actresses in Catwoman garb pawed at Adam West on the 60s TV show but the innuendos were relatively chaste. This film formally acknowledges the compatibility of their paraphernalia; taking those form-fitting animal costumes and bondage masks to their logical conclusions. It was Frank Miller who literally made Selina Kyle a professional dominatrix in the 1986 comic Batman: Year One and her use of a bullwhip dates all the way back to her first appearance in 1941, not long before Superman co-creator Joe Shuster was illustrating BDSM magazines to make ends meet.

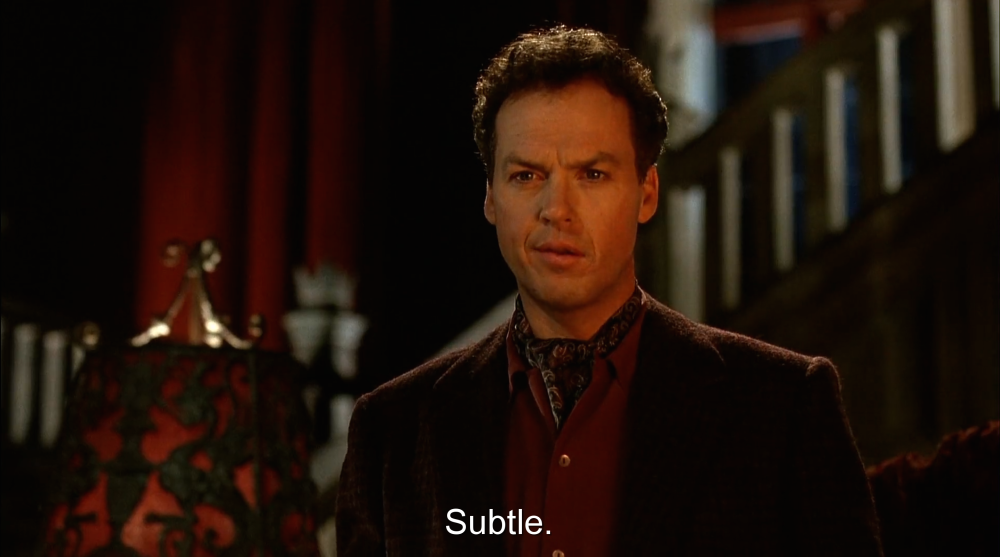

Michelle Pfeifer’s costume was the first Catwoman costume to be explicitly designed in homage to S&M. One of the funniest and subtlest jokes in the film is how unlike Joker or Penguin, two genuinely frightening looking individuals, it’s Catwoman’s appearance that startles Batman. He’s not used to fighting a woman, let alone one who so closely resembles himself.

Obviously, many fictional female antagonists have used their feminine wiles to get under the hero’s skin and manipulate them. In Dick Tracy (a film heavily influenced by Batman) Madonna was little more than a sexpot without without agency beyond double-entendres and the ability to tempt the titular hero away from his girlfriend. Camille Paglia praised her as a feminist icon not long after this, but compared to Catwoman, “Breathless Mahoney” isn’t what you’d call fierce, as in mmrow this kitten’s got claws. More so than any other superhero, Batman seems especially vulnerable to sexual advances getting under his mask of stoic solemnity precisely because he is so calculatedly implacable. Catwoman correctly guesses as much when she sucker-punches him twice during their initial encounter, first by feigning feminine weakness and then by grabbing his batjunk. It’s offscreen, but it’s there.

Batman’s suit was actually slightly desexualized from the first film, replacing what was previously sculpted abdominal muscles with streamlined paneling. This high-tech look better contrasts his own meticulous nerd sensibilities with Catwoman’s stitched-together suicide girl. In her own form-fitting bodysuit, perhaps it would have been too much for Batman to also appear next to her looking like a quasi-naked animal-man, with satyr-like horns.

For all the dramatic priority the first film placed on Bruce Wayne’s romantic and sexual pursuit of Vicki Vale, he’s never her object of desire when costumed as Batman. And for all of Catwoman’s matter-of-fact carnality, Burton’s camera never once objectifies her by lingering on any part of her shiny bodysuit, something which can’t be said of the many Catwoman-inspired women of comic book films like Barb Wire, Sin City, Aeon Flux or even 2004’s Catwoman, which attempted to reboot the character by sticking Halle Berry into a dreadful costume which rendered her half naked.

Audiences of children, male or female, did not have the necessary life experience to comprehend the overt sexuality of Batman Returns, which is one of the key reasons the film frightened them so much. Young women took to the freshness of Selina Kyle’s riot-grrl Catwoman. This leaves the young man’s take.At a superficial level, naturally, a good looking woman in a skintight costume with high heels gets a young man’s blood pumping; this is the image that superhero comic books have been using to prey on emotionally immature young men for decades. To the male moviegoing public then and now, it’s worth a chuckle as a sexual novelty although superhero aesthetics have become so ubiquitous in the mainstream that the novelty barely rouses attention anymore. Beyond the immediate visual impact of her Catwoman costume, Selina Kyle stands in for a certain type of woman in every young man’s growing taxonomy of women: the crazy chick who might fuck you. This may sound harsh, but if you’re a crazy guy like Bruce Wayne, it could also mean love!

Alpha males with no morals and some command of their sexuality look to a woman who is psychologically distraught and often conclude: dude, seriously, she’s fucking crazy bro, but she’ll fuck the shit out of you. Mental instability in women is usually correlated with either a high level of sexual energy, or an equally opposite pull to the direction of prudish chastity. Western culture’s increased promiscuity has led to a schizophrenic, contradictory attitude towards the purpose and necessity of sexual displays and at no time is this clearer than Halloween – the phenomenon of “sexy” Halloween getups for women and girls is a very recent one, resulting from the sexual revolution of the 1970s, and sexy cat ears continue to adorn the heads of young women ever year. Seeing Halloween-style attire on a female at any other time of year indicates some potential mental instability, and suggests sexual adventurousness. At the time Batman Returns was made, this would have applied mainly to either goth girls or punk chicks.

Reading Bruce Wayne in Daniel Waters high school parameters, he’s a nerd who dabbles in goth culture to intimidate bullies, so his immediate attraction to Catwoman is easily understood: a kindred spirit! As Batman he fancies himself a kind of gothic James Dean, the moody loner. Good girls can’t break through his shell. Vicki Vale just couldn’t get him, the real him, daddy-o. He needs another tortured soul to hang with at Denny’s around 3 AM.Bruce is mistaken. Batman and Catwoman are fundamentally incompatible; they may be animal-person alter egos but Selina’s DIY hand-sewn costume symbolizes the irreconcilable difference between them compared to Bruce’s vulcanized armor. They’re both freaks in one sense, but in terms of high school cliques she’s far more freak than Batman’s geek. With her more unpredictable persona, Catwoman is like the teenage punk chick who’s the subject of sophomore infatuation by a nerd, Batman. Nerds crush on punk, goth and miscellaneous misery chicks all the time who don’t want nothin’ to do with it. He’s drawn to the beauty of her nonconformity and detects their shared experience as outsiders, but can’t win her over because he’s still a dweeb who cares about the rules. Catwoman likes shoplifting and destroying private property, Batman likes to hang out in his basement tinkering with gadgets and doing research. It’ll never work. They’re both “creatives” but as Daniel Clowes once noted, beautiful art school girls are REAL TROUBLE! Girls like that might wreck their whole apartment to make a “statement” or start wearing cat ears in public to express her true self or something.

Catwoman flirts brazenly with Batman between punches and kicks but it feels more like overcompensation for her original awkwardness in front of him as Selina Kyle. The relationship which could work, and nearly does, is between the two when they’re out of costume. In Selina’s first, pre-Catwomanhood encounter with Batman, he saves her from a Red Triangle clown and she’s meekly grateful. In her post-Catwomanhood first encounter with Bruce Wayne, she’s undergone her mental break and he’s visibly turned on by the difference in attitude he sees from this formerly shy and reserved secretary.

Michael Keaton plays Bruce as a little more comfortable in his own skin than the first film, and unlike his fidgety fumbling with Vicki Vale, he doesn’t hesitate in his pursuit of Selina. She makes it clear that his response to her newfound sexual confidence isn’t unwelcome, but she’s “working.” It’s a real Mary Tyler Moore, career woman affirmation moment – breaking through the glass ceiling of costumed vigilantism after being thrown through the glass window of her office. To what degree does a woman’s career provide her with a sense of purpose, and happiness? Many career women I’ve known came from extremely unpleasant home situations; their independence was essential to no longer thinking of themselves as helpless victims.

In an unspoken way, the scene in Max Shreck’s office between Bruce and Selina implies that Bruce’s crazy-chick radar is beeping like crazy because if Max Shreck’s secretary is giving him lip, she must be nuts and c’mon, Michael Keaton loves to get nuts. Their romantic patter isn’t just easier because they’re not fighting each other on rooftops, they sense in each other an unhingedness just below the surface. Such divinations between otherwise normal looking weirdoes are, in fact, possible in real life. Secretive people can spot other secretive people, and between a man and woman the intrigue can become romance.

He also notices that she’s let her hair down since he first encountered her as Batman. A “practical” haircut on a woman is typical for mothers who have retired from the game. Shaved or partially shaved heads are a warning sign; a woman who hacks off any large portion of her hair is in some sense self-destructive. Selina Kyle’s hair length is at that perfect length for Michelle Pfeiffer to tuck her head into the Catwoman helmet, but still long enough to signal she’s bold in all the right ways, fellas.

For some guys that “crazy chick” hair could also signal there are damaged goods underneath to be exploited, but Bruce Wayne’s a good guy – he’s damaged goods himself.

When Selina mocks Bruce’s failed relationship with Vicki Vale, she does so after having gotten to know him well enough to mock his prior attempt at normality.

Seconds later, when they’re making out on the couch like teenagers, the scene becomes played for a joke as they separately realize that any removal of clothing will uncover their nocturnal scarring, which isn’t altogether different from how the situation would play out it they were both cutters.

Among the well-worn superhero movie conventions which Batman Returns unknowingly created was the formula of having two villains per sequel, and giving these pairs of antagonists a relationship beyond “we both hate the hero so let’s team up” is tricky. Catwoman’s temporary alliance with Penguin isn’t based on more than the declared need to destroy a common enemy, and doesn’t even hold up logically since she would probably have noticed that Penguin is already publicly allied with Max Shreck. Michelle Pfeiffer and Danny Devito only have two full scenes together in the entire film and they’re basically the setup and punchline to a joke about pretty girls getting ugly creeps to help do their homework, or frame Batman, depending. Every second of their introductions to each other is sexually charged, of course, with her rebuffing his animal grunts and advances just long enough to strike a partnership.

Questioning her legitimacy as a fellow rogue, Penguin pulls rank not just as a man but an ugly little man, chortling that she’s perhaps she’s just some typical wacky broad – “a screwed up Sorority chick who’s getting back at her daddy for not buying her that pony when she turned Sweet Sixteen.”

This is the insult commonly lobbed by ugly men and women at beautiful women: Yeah, you may be hot, but you don’t have the authenticity of struggling through life looking unattractive, like I do. You’re so spoiled, I bet your parents are probably rich, too.

Catwoman turns on the sexual charm just enough to ensure Penguin’s participation in framing Batman. When they meet again afterwards, he comes calling for what he thought was implicitly promised, going so far as to hand her a ring and propose they “consummate our fiendish union.” She says she wouldn’t touch him to scratch him. He doesn’t take it well.

Women using their wiles to manipulate men is such a dramatic cliché, people forget it happens in real life. Attractive women can do it so effortlessly that they do it unconsciously. Selina Kyle has a rather amazing line Waters’ original script which didn’t make it to the final film, when she infers that Penguin is quickly turning dangerous upon seeing his pussy entitlement evaporate:

Mature male adult sexuality requires acceptance that no amount of flirtation with the opposite sex ever guarantees anything. This is a hard if not impossible lesson for teenagers to learn since male teenage sexuality is a loaded gun, and we know Oswald Cobblepot’s sexual development was arrested sometime back during his teen years as a complete societal outcast. Spurned, he tries to kill Catwoman. The principle of this reaction is the same as when any loser flips out after experiencing the contempt of a girl out of his league, with whom he thought he had a chance.

The graduation from reading superhero comics to having a healthy sex life is the gauntlet every nerd faces at some point in his youth. It’s no coincidence that in the 1970s, when the first generation of comic book artists to have grown up on super heroes began professionally illustrating Batman et al, everything was suddenly rendered so much more realistically, down to and perhaps especially the physicality of the characters. This was the beginning of the degeneracy; in their efforts to give their beloved superheroes aesthetics which matched the stature they occupied in the artists’ minds, they idealized them in a way that quickly became a form of titillation for the mostly male reading audience.

An artist drawing Catwoman in the 1950s wouldn’t have considered the task to be any more representational of reality than Lil’ Abner. Twenty years later, talented artists like Neal Adams or Gene Colan couldn’t help adding some sex appeal with their capacity for more detailed anatomical work. The scripts were incorporating more adult themes by then, so why not? Twenty years after that you arrive at the open, shameless sexploitation of companies like Image, with series like Witchblade that ruthlessly pandered to the adolescent male audience’s market demand for cleavage on the covers.

The success of Batman ’89 led, eventually, to a present time wherein superhero obsession into adulthood has been extricated from the now-niche medium of comics and normalized in the mainstream. Women criticize the sexism that’s been part of the genre for so long when what they should really be upset at is a mainstream culture that retards men into playing videogames about Wolverine well into their 30s instead of raising families.Feminists insist that corporate America runs a patriarchal con to trick them into a life of child bearing domesticity, but capitalism is only as family-oriented as the culture it serves – by the time divorce rates were skyrocketing, corporate America picked up on the data that single urban women like Selina Kyle would have a lot more disposable income to squander on being an independent city gal than if she and a husband were budgeting for their child’s food, education and health care. Batman Returns never tells us what exactly Selina Kyle moved to Gotham City to become, and that’s not necessary to believe she could become Catwoman, but one wonders. What was her dream? To be the next Max Shreck?

One of the unsung appeals of the Batman franchise is how Gotham City, as opposed to the cities of many other superhero stories, is a depiction of urban life as a living hell, populated by human monsters from The Joker all the way down to the anonymous mugger who shoots your parents in Crime Alley. Clark Kent’s journey to Metropolis is revered as an essential step in his self-actualization into Superman, and Marvel Comics stories are usually love letters to New York. Gotham is the big city of the common man’s nightmares, held in a Jeffersonian disdain and demonstrating over and over again in every comic, film or cartoon that its reason for being overrun with bizarre menac