Partner Link

Partner Link

The infamous Dorian Gray was more innocent than I expected. Though he had the temptations of his own temperament, it took Walter Pater’s mimic in Lord Henry Wotton to seduce him to the “new Hedonism.” The opening scenes of The Picture of Dorian Gray seem nearly idyllic, pastoral, dare I say Edenic with the lush garden with its bee and spray of lilac.

Even when he begins the path of the new hedonism, there doesn’t seem much to bruise modern sentiment. The poisonous book doesn’t seem all that bad, especially following the aphorism of the preface that “there is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book.”

Perhaps then, I should be moved when Sybil Vane, like the lady of Shalott becomes “half-sick of shadows” and leaves fantasy for reality only to die. I should be sickened by Dorian and Harry’s romanticization of her death as a sublime tragedy or the sentiment that she was “less real” that Ophelia or Juliet.

But she is less real to the reader than Dorian and less seductive that the narrative persona that Wilde adopts. And isn’t she really only just as real as Ophelia or Juliet as a fictional character? Yes, he has murdered Sybil through his cruelty, “yet the roses are not less lovely for all that” and “the birds sing just as happily in [his] garden.”

Maybe I should have closed the book then and decreed with an early critic that to read this book was to “go grubbing in muck-heaps.”

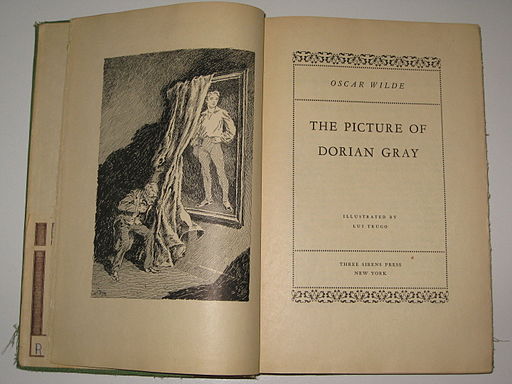

But the tale continues, and I continue with it. The picture has altered. Now there is a cruel look marring Dorian’s beautiful face, and I want to see what action will alter it further. I wonder with Dorian when the picture changes and what changes it:

The vicious cruelty that marred the fine lines of the mouth had, no doubt appeared at the very moment that the girl had drunk the poison, whatever it was. Or was it indifferent to results? Did it merely take cognizance of what passed within the soul? He wondered, and hoped that some day he would see the change taking place before his very eyes, shuddering as he hoped it.

I think that we will see the next alteration and the next sin, but time passes. The painting ages and alters and we learn very little of what it is that Dorian has done. We follow him through a luxurious life filled with empty parties and extravagant collections of fabrics and jewels and vestments. It’s almost as if his sin is the waste of luxury, of empty and banal overabundance.

But there are whispers and little hints. Not the whispers of Dorian becoming a papist as he exults in the luxury of ritual, but the hints of his time spent in disguise in houses of ill repute. There are also the lives that come up ruined. The suicides. The gentlemen who will no longer stay at the club when he arrives.

Why are the sins themselves so shadowy when the corruption of Dorian’s portrait is so apparent?

Yes, we witness real horror when Dorian finally shows the aging painting to its painter and then acts out in a moment of rage. And Dorian’s character is quite clear in the novel by that point.

But why not show the next sin and the next alteration long before blood gleams on the portrait’s hands?

Because there is something to the preface. This book may be obsessed with morality even as its author proposes that there is no such thing as a moral or immoral book. But, as Harry remarks, “the books that the world calls immoral are books that show the world its own shame.”

Wilde himself wrote that “each man sees his own sin in Dorian Gray.”

Whether we see the horror too late or rail against the novel as a “poisonous book,” we are all Dorian Gray.

Advertisements Share this:- More