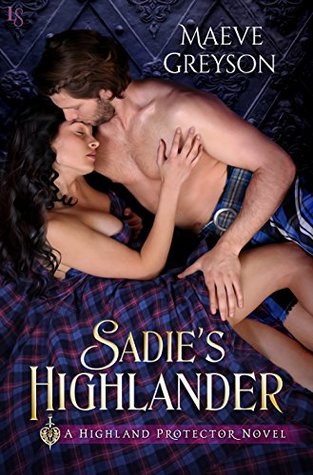

The Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) is often criticized for its loudness. According to measurements made in 2010, the noise reaches up to 100 decibels, enough to cause permanent hearing loss in the long term. This is why you should always wear earplugs on the BART, which can decrease the volume by up to 30 or so decibels, making it tolerable and harmless.

Source

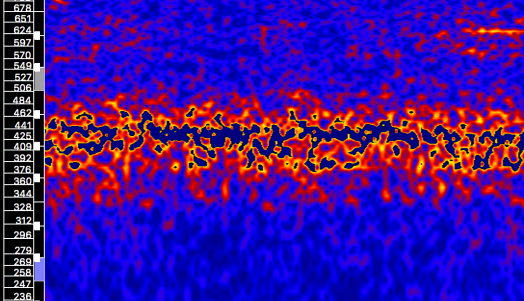

And while pointing out that BART gets really loud is indeed important, I would claim that there is something even more important to note. Namely, that BART is not merely loud, but it is also distinctly dissonant. Talking only about the stretch that goes from Millbrae to Embarcadero, an analysis I conducted reveals that the single worst period of dissonance happens on the ride from Glen Park to Balboa Park (at around the 20 second mark after one starts). If you are curious to hear it, you can check it out for yourself here. That said, I do not recommend listening to that track on repeat for any length of time, as it may have a strong mood-diminishing effect.

The full Glen-Balboa ride.

The full Glen-Balboa ride.  Zooming in the most dissonant region. Notice the hellstorm of dissonant pairs of tones.

Zooming in the most dissonant region. Notice the hellstorm of dissonant pairs of tones.

Too bad that some of the beautiful patterns found at the entrance of the Balboa Park BART station are not equally matched by beautiful sounds in the actual ride:

Balboa Park has some beautiful visual patterns (useful for psychophysics).

Ultimately, dissonance might be much more important than loudness, insofar as it tracks the degree to which environmental sound directly impacts quality of life. Thus, in addition to metrics that track how loud cities are, it might be a good addition to our sound contamination measurements to incorporate a sort of “dissonance index” into our calculations.

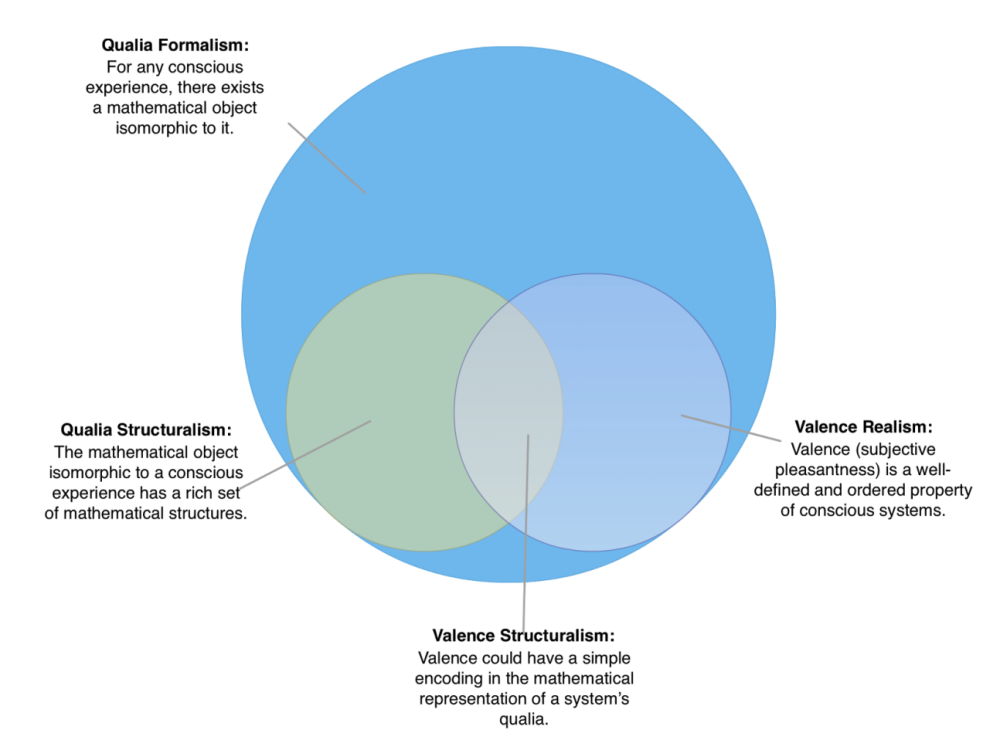

A General Framework for ValenceAt the Qualia Research Institute we have pointed that the connection between dissonance and valence may not be incidental. In particular, we suggest that it falls out as a possible implication of the Symmetry Theory of Valence (STV). The STV is itself a special case of the general principle we call Valence Structuralism, which claims that the degree to which an experience feels good or bad is a consequence of the structures of the object whose mathematical properties are isomorphic to a system’s phenomenology. The STV goes one step further and suggests that the relevant mathematical property that denotes valence is the symmetry of this object.

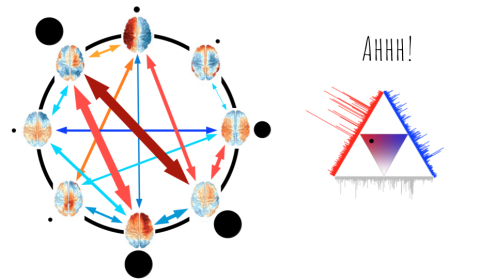

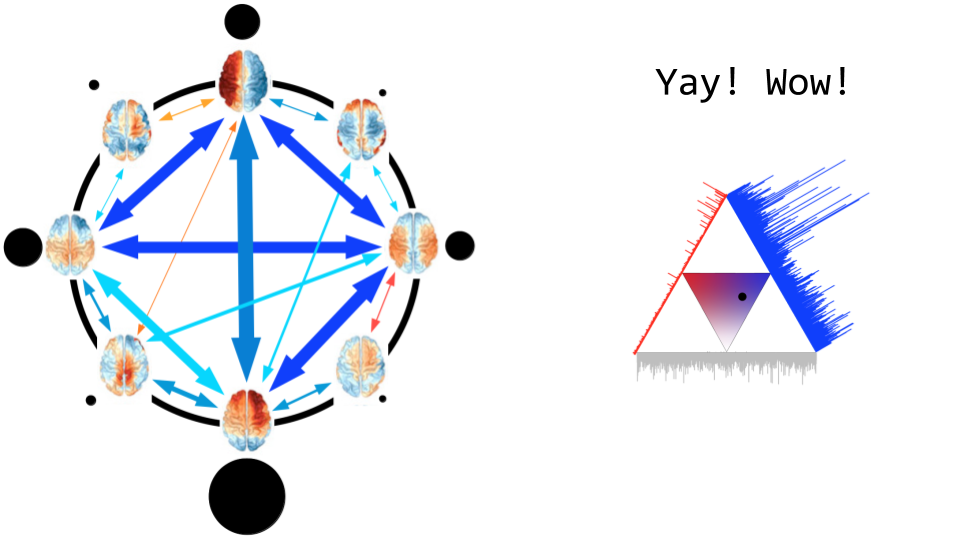

In Quantifying Bliss, we postulated that a general framework for describing the valence of an experience could be constructed in terms of Consonance-Dissonance-Noise Signatures (“CDNS” for short). That is, the degree to which the given states have consonance, dissonance, and noise in them. As an implication of the Symmetry Theory of Valence we postulate that consonance will directly track positive valence, dissonance negative valence, and noise neutral valence. But wait, there is more! Each of these “channels” themselves have a spectrum. That is to say, one could be experiencing high degrees of low-frequency-dissonance at the same time as high-frequency-consonance and maybe a general full-spectrum background noise. Any combination is possible.

Dissonant-dominant CDNS

Dissonant-dominant CDNS  Noise-dominant CDNS

Noise-dominant CDNS  Consonance-dominant CDNS

Consonance-dominant CDNS

The Quantifying Bliss article describes how recent advancements in neuroscience might be useful to quantify people’s CDNS (namely, using the pair-wise interactions between people’s connectome-specific harmonics).

Many Heads But Just One BodyRichard Wu has a good article on his experience with tinnitus. One of the things that stands out about it is the level of detail used to describe his tinnitus. At its worst, he says, he does not only experience a single sound, but several kinds at once:

By the way, its getting louder isn’t even the worst. Sometimes I develop an entirely new tinnitus. […] Today, I have three:

A very high-pitched CRT monitor / TV-like screech (similar to the one in the video). A deep, low, powerful rumbling. A mid-tone that adjusts its volume based on external sounds. If my environment is loud, it will be loud; if my environment is quiet, it will ring more softly.

As in the case of the BART and how people complain about how loud it is while missing the most important piece (its dissonance), tinnitus may have a similar reporting problem. What makes tinnitus so unbearable might not be so much the fact that there is always a hallucinated sound present, but rather, that such a sound (or clusters of sounds) is so unpleasant, distracting, and oppressive. The actual texture of tinnitus may be just as, if not more, important than its mere presence.

We believe that Valence Structuralism and in particular the Symmetry Theory of Valence are powerful explanatory frameworks that can tie together a wide range of disparate phenomena concerning good and bad feelings. And if true, then for every unpleasant experience we may have, a reasonable thing to ask might be: in what way is this dissonant? For example: Depression may be a sort of whole-body low-frequency dissonance (similar to, but different in texture, to nausea). Anxiety, on the other hand, along with irritation and anger, might be a manifestation of high-frequency dissonance.

Likewise, whenever a good or pleasant feeling is found, a reasonable question to ask is: in what ways is this consonant? Let’s think about the three kinds of euphoria uncovered in State-Space of Drug Effects. Fast euphoria (stimulants, exercise, anticipation, etc.) might be what high-frequency consonance feels like. Slow euphoria (relaxation, opioids, etc.) might be what low-frequency consonance feels like. And what about spiritual euphoria (what you get by thinking about philosophy, tripping, and taking dissociatives)? Well, however trippy this may sound, it might well be that this is a sort of fractal consonance, in which multiple representations of various spatio-temporal resolutions become interlocked in a pleasant dance (which may, or may not, allow you to process information more efficiently).

Now what about noise? Here is where we place all of the blunting agents. The general explanation for why anti-depressants of the SSRI variety tend to blunt feelings might be because their very mechanism of action is to increase neuronal noise and thus reduce the signal-to-noise ratio. Crying, orgasm, joy, and ragegasms all share the quality of being highly symmetric harmonic states, and SSRIs having a generalized effect of adding noise to one’s neuronal environment would be expected to diminish the intensity (and textural orderliness) of each of these states. We also know that SSRIs are often capable of reducing the subjective intensity of tinnitus (and presumably the awfulness of BART sounds), which makes sense in this framework.

The STV would also explain MDMA’s effects as a generalized reduction in both dissonance and noise across the full spectrum, and a generalized increase in consonance, also across the full spectrum. This would clarify the missing link to explain why MDMA would be a potential tool to reduce tinnitus, not just emotional pain. The trick is that both perceptual dissonance and negative affect may have a common underlying quality: anti-symmetry. And MDMA being a chief symmetrifying agent takes it all away.

Many further questions remain: what makes meaningful experiences so emotionally rich? Why do some people enjoy weird sounds? Why is emo music so noisy? What kind of valence can be experienced when one’s consciousness has acquired a hyperbolic geometry? I will address these and many other interesting questions in future posts. Stay tuned!

Share this: