The title of this post comes from the poem “Hymn,” which Sherman Alexie felt compelled to write after what took place in Charlottesville. And like him and countless others, including scores of teachers, I, too, have felt compelled to try to put into words some of what I’ve been thinking and feeling in the wake of those horrific events—if only to try to tame those thoughts and feelings, many of which were unsettling.

I’ve always struggled, for instance, with the concept of evil, not wanting to accept that there might be people or events that couldn’t be explained without resorting to the word ‘evil.’ But I simply can’t fathom the depth of hatred that the men and women who marched through that park with their torches, vile slogans and flags clearly held in their hearts. That depth of hatred seems to warrant the word evil, though even as I type it, I can feel myself flinch.

I also felt unsettled when the thought crossed my mind that the men and women who held those flags and barked out those taunting slogans had been children once—and as children  they had sat in classrooms in schools for many, many years. They were also children who as Nelson Mandela said (and our profoundly missed President Obama tweeted) were “born not hating another person because of the color of his skin or his background or his religion. [They had to] learn to hate, and if they can learn to hate, they can be taught to love.” And for better or worse, that led me to wonder what role our educational system may have played in bringing us to “the terrible kingdom.”

they had sat in classrooms in schools for many, many years. They were also children who as Nelson Mandela said (and our profoundly missed President Obama tweeted) were “born not hating another person because of the color of his skin or his background or his religion. [They had to] learn to hate, and if they can learn to hate, they can be taught to love.” And for better or worse, that led me to wonder what role our educational system may have played in bringing us to “the terrible kingdom.”

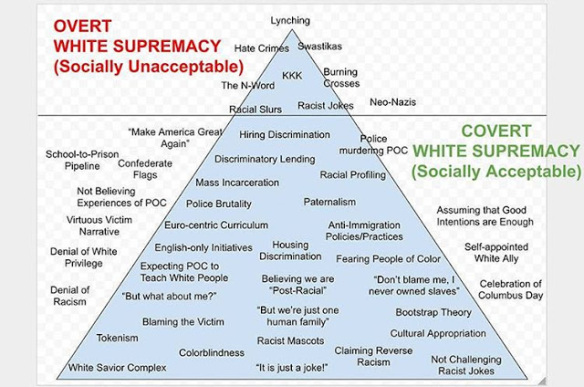

To be clear, I’m not in any way suggesting that teachers are to blame here—though, perhaps, we do need to become more assertive agents of change in schools. Nor am I calling for any compassion for those who carried those despicable flags and spouted those despicable words. Along with considering the existence of evil, the events of this week have also forced me to think that there are those among us who don’t deserve compassion. But I can’t stop thinking that our education system failed the children those white supremacists once were—not, to be sure, as much as we’ve historically and systemically failed children of color, but failed them nonetheless. And I think we failed them not only because of the unaddressed racism that permeates this country and manifests itself in both obvious and insidious ways, but because of the values and beliefs that lie at the heart of our system.

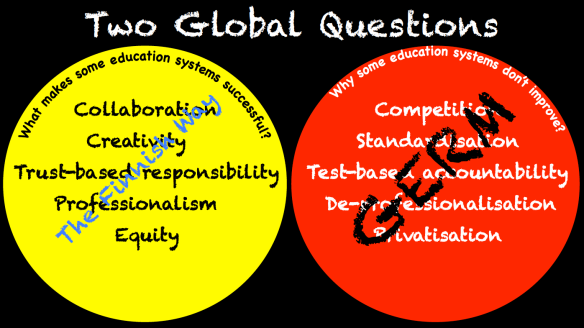

In his address to last year’s the Global Education Forum in Seoul, the great Finnish educator Pasi Sahlberg shared this slide. It pinpoints the differences between Finland’s approach to education and that of the Global Educational Reform Movement (a.k.a., GERM), which includes the United States, as a way of answering the question of what makes some education systems successful, while others don’t improve.

Clearly these two approaches are grounded in very different belief systems. And it doesn’t seem far-fetched to me that systems based on competition and standardization—coupled with a President who has no moral compass and divides the world into winners and losers—could lead to the kind of dog-eat-dog/”You will not replace us” talk that was on display in Charlottesville. It’s also a system that de-professionalizes and distrusts teachers. And it’s interesting to note that in a talk Sahlberg gave at a private school in New York, he not only shared that there were no private schools in Finland, but that there was no word for accountability in Finnish. Instead, he suggested that “Accountability is what happens when responsibility is subtracted,” and I think responsibility comes with trust.

So what do we at this terrible juncture? And who do we need to become, beyond people who are aware of—and reflect on—the covert ways racism rears its ugly head?

Over the next few weeks I’ll humbly try to share some teaching moves and shifts in practice that I think can help move us closer to the collaborative, creative and trust-based classrooms I believe our students deserve. But for now I’d like to share links to the following blog posts and articles, all of which offered me a sense of support, if not solace:

- Kylene Beers’s must-read post “And School Begins,” where she identifies five specific things you can do to support equity for all the students in your rooms—both those who are at the effects of oppression and those who run the risk of becoming oppressors.

- “Yes, Race and Politics Belong in the Classroom,” an EdWeek piece by H. Richard Milner that offers ten tips for engaging students in difficult conversation.

- “There Is No Apolitical Classroom: Resources for Teaching in These Times,” which was put together by NCTE’s Standing Committee Against Racism and Bias in the Teaching of English.

- And Jess Lishitz’s brave, poignant blog post, “How Am I Supposed to Confront White Supremacy and Racism on the First Day of School?” where she wrestles with how to welcome a new group of students to fifth grade in these troubled, complex times.

And finally, there’s this: While for better or worse, this week has led me to believe that some people are simply unredeemable, I reject the idea that any child is. Like Sherman Alexie who, in “Hymn” admits that he has “some empathy/for the boy [Trump was]” because of his “sandpaper father, who roughed and roughed/and roughed the world” and didn’t love him enough, I believe every child deserves empathy and compassion, no matter how prickly or unruly they are or how distant or unreachable they may seem. And so I’d like to share two last pieces:

- “Hugging a Porcupine” by Rob Miller who, in this powerful essay, reminds us that every child in our schools belongs to us and we must care for them as we’d care for our own.

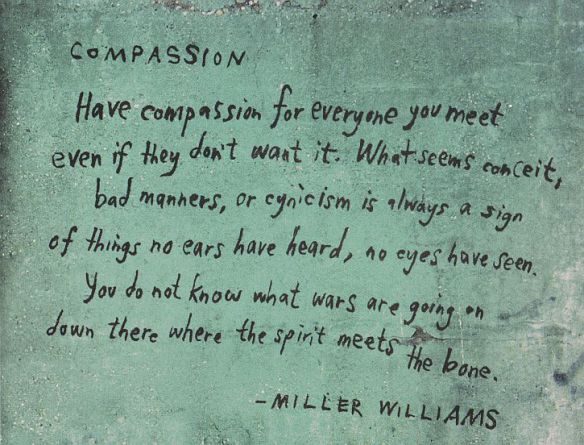

- And this poem by Miller Williams, which I discovered at the #compassionpoem page teacher Steve Peterson created, where you just might find a few other poems that actually offer solace: