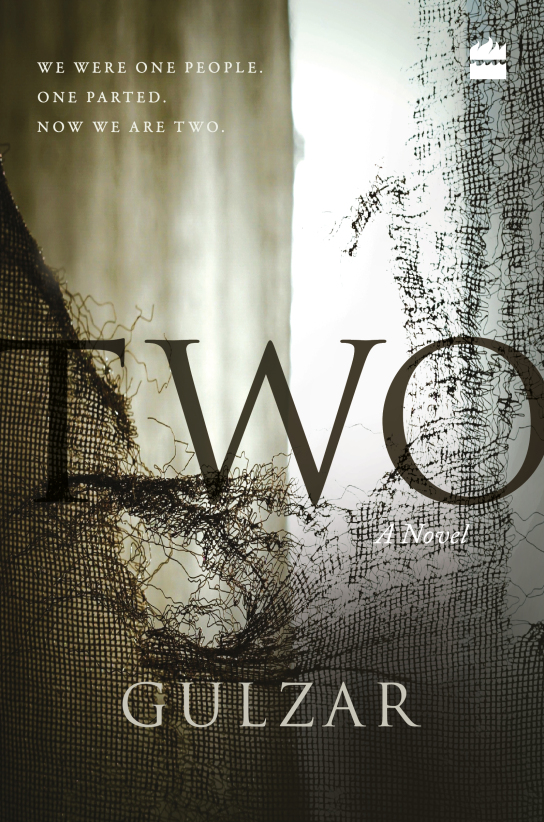

Believe it or not, Two is Gulzar’s first full-length work of fiction in English. (Photo courtesy: Wikimedia Commons)

Believe it or not, Two is Gulzar’s first full-length work of fiction in English. (Photo courtesy: Wikimedia Commons)

Imagine a compellingly chiselled poem expanded to become a story in prose. Or, imagine the opposite, a story compressed with such refined elegance that it becomes a poem. Take even a third alternative: a screenplay that could, if expanded, become a novel, and, if condensed, is transmuted into a poem.

Gulzar’s first attempt at a longer work of fiction is all three in one: a poem, a screenplay, a novel. It is a poem because the imagery reads like one; it is a screenplay because each episode is like a picture unfolding before your eyes; and it is a novel because it tells a story in a format that is neither a poem nor a screenplay.

Gulzar Saheb has often joked with me that he wished he could write a ‘full-length’ novel like I wrote once. I am glad that he hasn’t tried to. The reason for this is simple: his new work is of just the right length, longer than a short story, and shorter than a full-fledged novel. In doing so, it retains dramatic brevity of a short story, but has the texture of a novel.

A novella has been the subject of much literary scrutiny. It somehow defies conventional categorization, but in this very act of creative defiance lies the secret of its intense impact. The genre is not new. Munshi Premchand wrote several. So did Albert Camus (The Stranger), Ernest Hemingway (The Old Man and the Sea) and George Orwell (Animal Farm), to mention but a few examples.

A fiction is a work of fiction. Its size does matter, so long as its impact and quality indubitable. Why should the number of pages determine the quality of literary expression? Who decides how long a work of fiction should be? Should a story end when the reader is yearning for it to continue, or should it last till the reader begins to wonder when it will end? Fiction that is a tome is legitimate if it holds the attention of the reader; similarly, fiction that is shorter is equally valid if it keeps the reader enthralled. Limitations of any kind to the canvas of creative expression are arbitrary impositions of critics. The key question is whether the story being rendered is complete enough, whatever its length, to convey in a gripping manner the theme animating the writer.

In his book Different Seasons, a collection of four novellas, Stephen King called the novella ‘an ill-defined and disreputable banana republic’. Perhaps, it was an act of overstated and deliberate self-deprecation, because his readers found them as readable as ever. On the other hand, the Irish writer McEwan wrote in The New Yorker (12 October 2012) that ‘the novella is the perfect prose fiction’. It retains focus, moves at a faster pace, covers the same canvas as a novel but with far greater intensity, brings in necessary details but cuts out the unnecessary factual meanderings, and allows characters to blossom while omitting the verbal flab. It is as readable as a novel and, arguably, more satisfying than a short story. In other words, it is the perfect literary modus vivendi, offering to the reader a novel that is shorter than a work of fiction that is too long, and a work of fiction that is as satisfying as a novel but not too short.

Of course, as is true of all literary genres, the success of the novella depends not on the nature of its structure alone, but far more importantly, on the literary dexterity of the person who writes it. When Gulzar embraces the format, the novella has met a truly consummate partner. As proof, one has only to read Two.

Two is about the Partition of 1947, a cataclysmically tragic event that lived through. Even as Independence drew nearer, British cartographers worked overtime to draw the boundaries of two nations, one India, the other Pakistan. What was one became two, separated by an unbridgeable gap that made millions refugees overnight. Some ten fifteen million people – men, women, children, young and old – were displaced by a destiny they did not choose. It is estimated that some two million lost their lives in the frenzied bloodbath that accompanied this division.

Time erases wounds, but memories remain, like smouldering embers below the ash even when the fires of history appear to have died. Two is about those memories, those embers, recalled through a story that transports you to the agonies and dilemmas of ordinary people, both Hindus and Muslims, who suffered as a consequence of the Partition.

It is written in Gulzar’s inimitable – and riveting – style. The narrative, involving a bunch of characters who could be you or me or people we know, unfolds, scene by scene, in a manner that brings the traumatic days leading 1947 vibrantly – even painfully – alive. Each character is unique, and will remain etched minds, not by the length of the description, but by the writer’s ability to make the portrayal come alive through just a flourish of linguistic colour, a trait, a gesture, an expression, a situation, a dialogue, or even an abuse.

But Two does not end with the Partition. It carries us along, to decades later, where, in the strangest ways, the strands that unravelled in 1947 come together. In that journey, the 1984 riots against the Sikhs become a metaphor for the continuance of hate and violence in societies. The same emotions that made the Partition one of the most gory chapters of India’s modern history are now repeated in entirely different circumstances, only to prove the point that the irrational and warped furies that lurk just below the surface of ‘civilized’ societies can be easily triggered even when the past should have taught us to overcome them resolutely.

Gulzar Saheb’s debut as a novelist is a spectacular one. Two is unputdownable because the narrative is in the hands of a craftsman for whom words are like clay in the hands of a potter. Gulzar writes with the eye of a sensitive film-maker, the feel of a poet, and the touch one who has himself been singed for life by the story he narrates. Long after we put the book down, the characters, and the series of events which they become pawns in the sweep of history, continue to haunt us. One continues to read the book long after having finished its last page.

Written by Pavan K. Varma.

Excerpted from the Introduction of Two, written by Gulzar and published by HarperCollins India. Coming soon to stores. Pre-orders open at leading online bookstores.