by NONA BLYTH CLOUD

December is a very busy time for most people now. We have lots of celebrating, and gift buying and giving, going on. But we sometimes get a chance to slow down for a few days here and there.

Poets who lived before the 20th century often wrote longer poems than most poets do today, and this week’s subject is no exception.

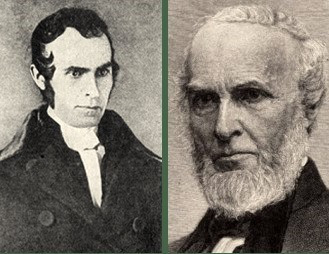

John Greenleaf Whittier (1807-1892) lived at a time when reading was one of the biggest entertainments available. He was in his late fifties in 1866 when he published his book-length poem Snow-Bound. It brought him much acclaim, but also financial security for the rest of his life.

I can think of few poets today whose poems bring in substantial income. Poets must do other work to survive, whether it’s writing novels, teaching others about writing, or writing non-fiction – criticism, essays or how-to books. Some poets have non-writing jobs, like insurance executive or social worker. “Bard” used to be an honored profession, but unless you’re writing song lyrics for hit singles, that time is long past.

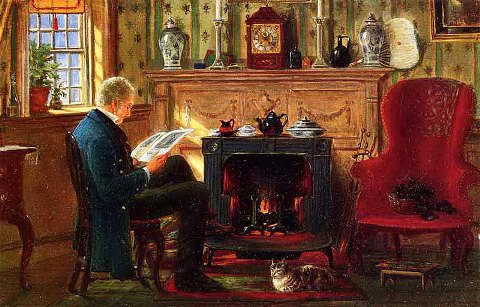

I’m only giving you one complete poem, one of Whittier’s shorter but still-lengthy poems. It was written later in his life, as he mused before the fire on past, present and future.

_____________________________________________

Burning Drift-WoodBefore my drift-wood fire I sit,

And see, with every waif I burn,

Old dreams and fancies coloring it,

And folly’s unlaid ghosts return.

O ships of mine, whose swift keels cleft

The enchanted sea on which they sailed,

Are these poor fragments only left

Of vain desires and hopes that failed?

Did I not watch from them the light

Of sunset on my towers in Spain,

And see, far off, uploom in sight

The Fortunate Isles I might not gain?

Did sudden lift of fog reveal

Arcadia’s vales of song and spring,

And did I pass, with grazing keel,

The rocks whereon the sirens sing?

Have I not drifted hard upon

The unmapped regions lost to man,

The cloud-pitched tents of Prester John,

The palace domes of Kubla Khan?

Did land winds blow from jasmine flowers,

Where Youth the ageless Fountain fills?

Did Love make sign from rose blown bowers,

And gold from Eldorado’s hills?

Alas! the gallant ships, that sailed

On blind Adventure’s errand sent,

Howe’er they laid their courses, failed

To reach the haven of Content.

And of my ventures, those alone

Which Love had freighted, safely sped,

Seeking a good beyond my own,

By clear-eyed Duty piloted.

O mariners, hoping still to meet

The luck Arabian voyagers met,

And find in Bagdad’s moonlit street,

Haroun al Raschid walking yet,

Take with you, on your Sea of Dreams,

The fair, fond fancies dear to youth.

I turn from all that only seems,

And seek the sober grounds of truth.

What matter that it is not May,

That birds have flown, and trees are bare,

That darker grows the shortening day,

And colder blows the wintry air!

The wrecks of passion and desire,

The castles I no more rebuild,

May fitly feed my drift-wood fire,

And warm the hands that age has chilled.

Whatever perished with my ships,

I only know the best remains;

A song of praise is on my lips

For losses which are now my gains.

Heap high my hearth! No worth is lost;

No wisdom with the folly dies.

Burn on, poor shreds, your holocaust

Shall be my evening sacrifice!

Far more than all I dared to dream,

Unsought before my door I see;

On wings of fire and steeds of steam

The world’s great wonders come to me,

And holier signs, unmarked before,

Of Love to seek and Power to save,—

The righting of the wronged and poor,

The man evolving from the slave;

And life, no longer chance or fate,

Safe in the gracious Fatherhood.

I fold o’er-wearied hands and wait,

In full assurance of the good.

And well the waiting time must be,

Though brief or long its granted days,

If Faith and Hope and Charity

Sit by my evening hearth-fire’s blaze.

And with them, friends whom Heaven has spared,

Whose love my heart has comforted,

And, sharing all my joys, has shared

My tender memories of the dead,—

Dear souls who left us lonely here,

Bound on their last, long voyage, to whom

We, day by day, are drawing near,

Where every bark has sailing room.

I know the solemn monotone

Of waters calling unto me;

I know from whence the airs have blown

That whisper of the Eternal Sea.

As low my fires of drift-wood burn,

I hear that sea’s deep sounds increase,

And, fair in sunset light, discern

Its mirage-lifted Isles of Peace.

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

His friends called him Greenleaf.

Whittier did have another calling. The life’s work to which he dedicated himself was the abolition of slavery. He was born on a rural homestead in Haverhill, Massachusetts, into an extended Quaker family. He was color-blind and in frail health, so although he received little formal education as a child, he was an avid reader, mostly his father’s books on Quakerism. Books were a luxury in that cash-poor household.

One of his sisters sent his first poem, without telling him, to the Newburyport Free Press, and its editor, William Lloyd Garrison, published it in 1826. Because of this, he was encouraged to attend the Haverhill Academy. To pay the school fees, he worked for a shoemaker, and his family paid the balance in food from their farm. In the fall and winter of 1827-1828, he studied hard, completing his high school education in just two terms.

Inspired by Garrison, he became a passionate abolitionist, publishing an antislavery pamphlet, Justice and Expediency, demanding immediate emancipation, and became a founding member of the American Anti-Slavery Society. He signed the Anti-Slavery Declaration of 1833, which he believed was the most significant action of his life.

He became a lobbyist and public speaker for the anti-slavery cause. While he won a few congressional leaders over, he was also mobbed, stoned and run out of some towns on his speaking tours. From 1838 to 1840, he was the editor of The Pennsylvania Freeman, which had to move to a new office after the first one was burned by a pro-slavery mob.

There was a bitter split between Whittier and Garrison in 1839, because Whittier believed that moral suasion was not enough, but that political action was essential to bring about legislation that would compel change. He was a founding member of the new Liberty Party that year, and attended the 1840 World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. Whittier persuaded Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow to join the Liberty Party. He continued to take jobs editing for newspapers, and wrote abolitionist broadsides and essays, such as The Black Man, which included the story of John Fountain, a freedman who was jailed in Virginia for helping slaves escape. After Fountain was released, he thanked Whittier for bringing attention to his plight, and went on a speaking tour to relate his experiences.

Whittier had a physical breakdown in the 1840s, his uncertain health further undermined by his travels, his editorial duties, and injuries from mob violence. He continued to advocate in writing for the Liberty Party’s expanding platform as other issues were added, and the party evolved into the Free Soil Party, but was no longer able to endure the rigors of extended travel or the hazards of public speaking. He was a supportive correspondent with other writers, several of them women, such as Sarah Orne Jewett and Celia Thaxter.

Throughout this period, he wrote poetry, most of it about slavery. But once the Civil War was over, and the 13th Amendment was passed, he began to write more philosophical and personal poems. He was one of the first contributors to Atlantic Monthly magazine.

The success of Snow-Bound took him completely by surprise; he earned $10,000 from the first edition alone, a huge sum in an era when a carpenter earned little more than $900 in a good year. It was a nostalgic portrait of his family, but also of rural New England, in the years before the Civil War.

John Greenleaf Whittier died on September 7, 1892, at the age of 84. There are many buildings, streets and schools named after him in New England, and cities in Alaska, California and Iowa named Whittier.

_____________________________________________

He was an idealist who viewed humankind’s future with great hope. In his poem, My Triumph, he addresses a few stanzas to the poets of future generations:

Hail to the coming singers!

Hail to the brave light-bringers!

Forward I reach and share

All that they sing and dare.

The airs of heaven blow o’er me;

A glory shines before me

Of what mankind shall be,—

Pure, generous, brave, and free.

A dream of man and woman

Diviner but still human,

Solving the riddle old,

Shaping the Age of Gold!

We can only hope to someday bring his vision to fruition, out of the chaos and divisiveness that are with us yet in the 21st century.

_____________________________________________

For those who have the curiosity – and patience – here’s a link to Snow-Bound:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45490/snow-bound-a-winter-idyl

- Burning Driftwood: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45485/burning-drift-wood

- My Triumph: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45488/my-triumph

- The Poetry of John Greenleaf Whittier: A Reader’s Edition, edited by William Joliff, Friends United Press (2000)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Greenleaf_Whittier

- https://www.biography.com/people/john-greenleaf-whittier-9530347

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Greenleaf-Whittier

- https://www.nps.gov/people/john-greenleaf-whittier.htm

- Theodore Duret, painted by Jean-Edouard Vuillard

- John Greenleaf Whittier as a young man, and as an old one

- Autumn Gold

Word Cloud photo by Larry Cloud

Share this:- More