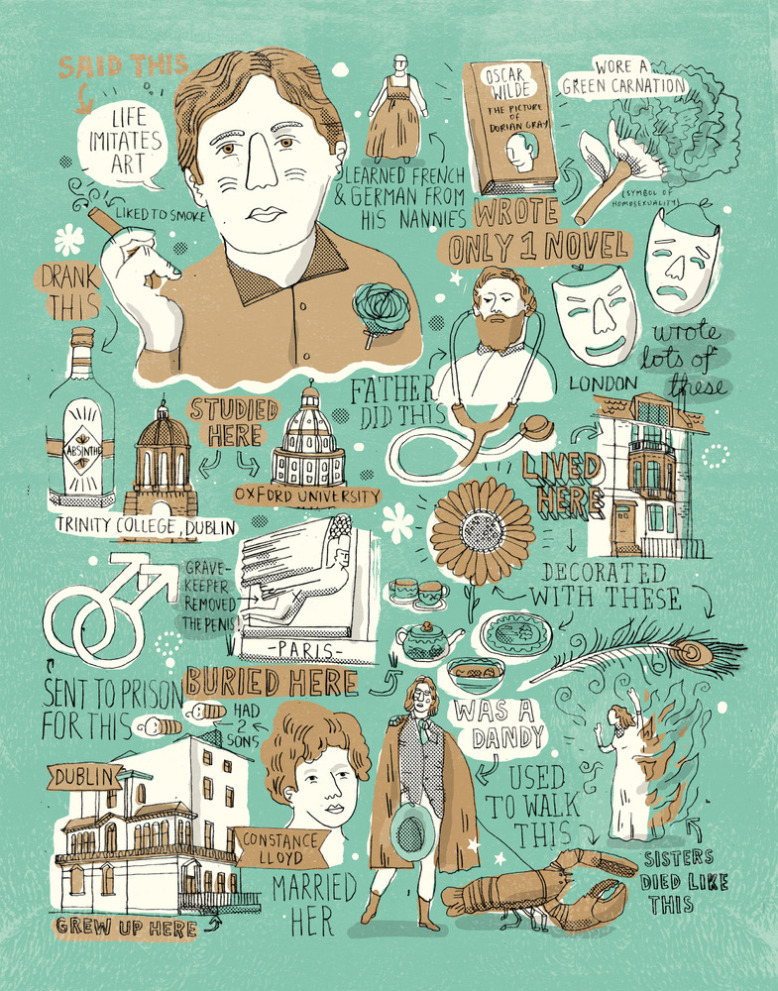

There was a time when I was seriously obsessed with the lives of writers: I read accounts of how they spent their time, I did a lot of research to find out who their influences were and I swore to see every documentary there is detailing their lives.

I wanted to know everything about them and all of that was just me being extra, because I wanted to get the secret formula of how to be a legit writer.

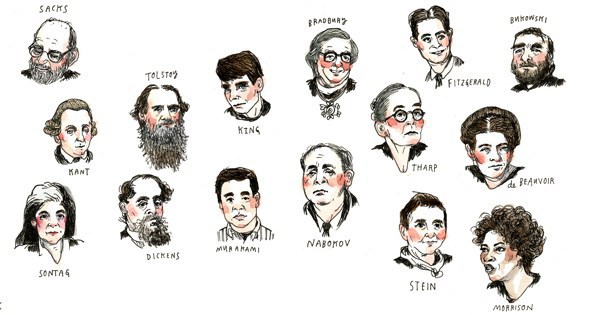

By: Wendy McNaughton

And then I came across this:There are three rules for writing a novel. Unfortunately, no one knows what they are.

— Somerset Maugham

That, along with reading more books made me realize that really, you just have to do it.

But then there’s the idealistic + romantic side of me which yearns to have days like this, five out of seven: wake up and meditate, sip coffee while writing my morning pages, transition to “real writing” (whatever that means), walk + run + be outside, have a decent lunch, edit in the afternoon, see friends/be social in the evening.

But I’m not Marcel Proust, as much as I love him, because I did not grow up rich therefore I have to worry about feeding and supporting myself. Which is where Manjula Martin’s book comes in handy — Scratch: Writers, Money and the Art of Making a Living (Amazon | Indie Bound) — as I try to make sense of what it means to be a writer, beyond the writing part.

Scratch is a collection of essays and interviews edited by Martin, a different kind of a backstage pass on how writers “make it.” And when I say “make it,” I don’t just mean once they’ve been published, but how they manage their day-to-day existence. Like, how do they pay their bills? Do they go on vacations? Do they have enough food?

By James Gulliver Hancock

What I love about this book is that the writers take us further deeper — the struggle of physiologically, mentally, emotionally supporting themselves while bravely and painstakingly committing pen to paper.

Most of the pieces resonated with me, but only a few really stood out. One of those pieces is J. Robert Lennon’s Write to Suffer, Publish to Starve which unpacks the craft, the process, the not-so-glamorous process of writing, and even its relationship to commerce. Consider it a no-bullshit guide to the literary world. No romanticizing, just straight up real talk.

…for most of us, writing is not particularly pleasurable, and publishing does not make us money. Most writers I know work in a state of perpetual anxiety and self-disgust, and regard the products of their labor as profoundly disappointing.

Writing is not coal mining. It is merely a pain in the ass, albeit one that tends to invite psychic distress, especially given the bewilderment with which it is greeted by a writer’s loved ones, once they realize what one actually does all day writing i.e., not much. Maybe a more appropriate rallying cry would be, “Write to suffer, publish to starve.”

His words provided some reprieve, a humbling affirmation to the struggles of writers slumped on their desks silently cursing the pages/screen in front of them.

That is writing, along with more lonesome, painful things. That is writing, bearing to sit with yourself as you become perpetually vulnerable, on the paper. That is writing, no matter how time hounds you with chores, responsibilities and other duties.

You keep at it, because you are hungry, just as Rachael Maddux wrote in Staying Hungry:

I felt shaky. I still do. Often I feel I’m welcoming the symptoms of starvation, which seem as applicable to a human body as to a writing career: anxiety, depression, muscle atrophy, stunted growth, compromised immune response, death. (When I first stopped freelancing, I certainly ate more actual food to keep the uncertainty at bay). For the first time, I began to ask myself what I was writing toward. It’s a question that I’m still trying to answer. Before, I may have said I wrote because it was all I wanted to do — or, in more insufferable moments, because it was what I was born to do. Maybe that’s so. But we are born hungry, too. The trick is learning how to feed yourself and not choke.

By James Gulliver Hancock

So after your long-awaited novel is finished, what happens next? Before I even get to that part, Martin was kind enough to impart the wisdom we all need to start looking at the writing process differently and more importantly, on realistic terms.In the piece The Best Work in Literature penned by Martin herself, she wrote:

A writer needs financial stability – a paycheck, preferably steady – to enable her best work. This is fairly self-evident: people need money to live, and writing rarely pays well or at all, so it follows that a day job will “free” a writer to concentrate on writing instead of earning, and hopefully she’ll write something amazing.

Even Malinda Lo wrote along the same lines, in A Sort of Fairy Tale.

The fact is, financial necessity can be extremely clarifying. When your goal is to make enough money to pay the rent, writing loses a lot of its artistic mystique and becomes something much more mundane: a job.

While I dream of quitting my day job so that I can write full-time (or live like I’ve outlined above), there is a sense to what Martin and Lo are referring to. I don’t want writing to ever feel like it’s only a job, a means to make ends meet. I’m still attached to keeping it as authentic and as genuine as much as possible, so that at the end of the day I can say that I’ve done my best work — with or without money, published or not.

There are many more pieces in the book truly worthy of being read, digested and internalized, like Harmony Holiday’s Love for Sale and Alexander Chee’s The Wizard.

If I were to sum up this book on my own terms, it would be this:

it’ll always be hard (it doesn’t ever get easier for anyone)

don’t quit your day job (financial stability enables your work’s integrity)

and always, write like hell.

* * *

Scratch: Writers, Money and the Art of Making a Living by Manjula Martin (Amazon | Indie Bound)

Scratch: Writers, Money and the Art of Making a Living by Manjula Martin (Amazon | Indie Bound)

Simon & Schuster

January 3, 2017 (304 pages)

My rating: ★★★★