Narrative poetry is essentially any type of poem that tells or intimates a story — one with plot, characters, setting, and a discernible point-of-view. Even so, most narrative poems do not fully articulate a story so much as construct its scaffolding and allude to its content with imagery and lyricism.

The contradiction between narrative poetry’s form and function begs an obvious question: WTF, exactly, is the point of it? If you want to construct a narrative, why not commit? Focus on the elements of the narrative itself, rather than its physical poise as words on a page. And if you want to write a poem, why saddle it with the burden of narrative, which is, by nature, prosaic.

I’ve wondered this a lot—especially sitting in graduate poetry workshop during an exercise that involved passing around a bag of jumbo lego blocks for inspiration, and then watching those same students bring their “prose poems” into fiction workshop where serious writers stared at them, befuddled, with no constructive feedback to offer because the creations themselves were unconstructive. Of course, a prose poem is more prose than poem and doesn’t constitute narrative poetry, but the idea of blending media for artistic amusement is at work in a similar way.

Look, Mom. I’m doing a poem.

Look, Mom. I’m doing a poem.

Out of spite for poetry (or for what I gathered it had become), I used to lift entire passages from my short stories and simply add line breaks, turning these in as “narrative poems.” My peers applauded them. I was like Bukowski, they said. At the end of the semester, in my most defiant lampoon, I typed all thirteen of my poems onto the same sheet of paper by feeding it through a Smith Corona DeVille in different directions, splattered ink across the page, and turned this in as a creative final. Though not a single poem remained legible, the class was unanimously impressed.

The great poet Christopher Logue once commented in a 1993 Paris Review profile, “So much of the poetry that is published and praised today seems to be the work of self-indulgent windbags, people who imagine that self-expression is a justification for writing. It is easier to become the president of the United States than a good poet.” I suspect this is true any time a “poet” starts fooling around with structure and style because they’ve run out of worthy content.

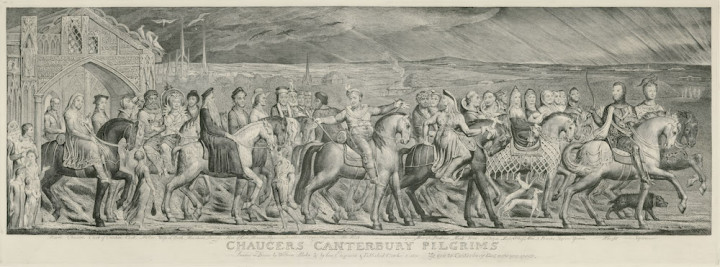

“So much of the poetry that is published and praised today seems to be the work of self-indulgent windbags.”Of course, my resistance to narrative poetry is mostly a reaction to its contemporary form. The incarnations of narrative poetry are so diverse that it’s almost meaningless to give the genre one label. I would be silly to criticize the classical examples we have in Homer’s Iliad, Milton’s Paradise Lost, Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, or Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. You might trace these works back to some early effort to set oral tradition to verse, that it might be better remembered and transmitted through the ages. In that case, utility is clear, and form matches function.

Hundreds of years later, the modernists treated narrative poetry as an opportunity to experiment. Meter and rhyme slipped slowly into extinction, and writers mixed more prosaic storytelling with mild lyricism for an end result that was less than lucid. Still, these poems were distinct from lyric poems—different than, say, “Ode to a Nightingale,” because they prioritized narrative elements over aural and visual effect. Take Robert Frost, who is unfortunately best known for his “Road Not Taken” poem, but whose later North of Boston collection was written with deliberately plain language and a strong narrative focus. The poems within are mostly rhymeless and meterless, and each one a sort of micro-drama. In a 2013 article for Virginia Quarterly Review, poet and essayist Dana Gioia suggests the collection “. . . has never been adequately appreciated for its radical reinvention of the modern narrative poem.” And there are other modernist examples, among them Robert Penn Warren, T.S. Eliot, Edwin Arlington Robinson.

I let my neighbour know beyond the hill;

And on a day we meet to walk the line

And set the wall between us once again.

We keep the wall between us as we go.

To each the boulders that have fallen to each.

And some are loaves and some so nearly balls

We have to use a spell to make them balance:

“Stay where you are until our backs are turned!”

We wear our fingers rough with handling them.

Oh, just another kind of out-door game,

One on a side. It comes to little more:

There where it is we do not need the wall:

He is all pine and I am apple orchard.

My apple trees will never get across

And eat the cones under his pines, I tell him.

– From Robert Frost’s “Mending Wall”

The past 30 years have seen a resurgence of narrative verse, and this new contemporary period takes a sharper turn toward obfuscation. Something is lost in the process, and that something is narrative itself. Brian McHale describes the shift in a 2001 essay for Narrative: “Postmodernist poets resort to various strategies of having their cake and eating it too, of telling stories without committing themselves to master-narratives wherein such stories are inscribed.”

Looking at examples such as Michael Palmer’s Notes for Echo Lake or Fraser’s When Time Folds Up, it’s fair to conclude that contemporary narrative poems are much more interested in evoking the verisimilitude of story to give their otherwise perplexing language some sustaining fiber of interest than they they are in undertaking the labor of story, or perhaps they undertake labor, but that labor is warped and redirected—a game of equivocation. As R.T. Smith writes, “In an era of so much poetry with fractured syntax—fragmented, elliptical, dissonant, cryptic—I sometimes grow restive and wonder who really has a story to tell and who is just feigning it, juking about, confusing obscurity with profundity.”

Beginning and ending. As a work begins and ends itself or begins and rebegins or starts and stops. Ideas as elements of the working not as propositions of a work, even in a propositional art. (Someone said someone thought.)

That is, snow

a) is

b) is not

falling-check neither or both.

If one lives in it. ‘Local’ and ‘specific’ and so on finally seeming less interesting than the ‘particular’ wherever that may locate.

“What I really want to show here is that it is not at all clear a priori which are the simple colour concepts.”

Sign that empties itself at each instance of meaning, and how else to reinvent attention.

Sign that empties . . . That is he would ask her. He would be the asker and she unlistening, nameless mountains in the background partly hidden by cloud.

– From Michael Palmer’s “Notes for Echo Lake 1”

Is it valid to argue that poems don’t owe the same kind of allegiance to narrative that a short story or novel might, and that it’s acceptable to flirt with narrative without consummating? Perhaps. This argument depends on the idea that poems have merit outside of their content, that they can be cherished for linguistic texture and evocative imagery in the same way music can be cherished for its “vibe” or a simple motif within, even when listeners fail at interpretation (thinking of the Beatles’ “Come Together”). Edward Hirsch explains the dual function of poetry in a 2006 article on epic, drama, and lyric:

“I emphasize the magical effectiveness of words as words, but I’m also aware that poetry has a strong relation to music on one side and to painting on the other. It has a musical dimension, [and] a pictorial element. Poetry and music are sister arts. So are poetry and painting. It’s as if the eye and the ear were related through poetry, as if they had become siblings, or lovers.”

“Poetry has a strong relation to music on one side and to painting on the other.”Music is music, painting is painting, stories are stories, and poems are poems, but they all employ language and artifice. They are unique, but related. Who is to say what rules govern each? And if there were rules, who but writers would hold the pen, and who but readers would hold the gavel?

Maybe the simple conclusion is that narrative poetry is poems telling stories, and that’s the point of it, and that point is okay. But as with any literary endeavor, the challenge is to create something that completely fulfills its own designs, delivers on every insinuated promise. The challenge is to create “a drawing [with] no unnecessary lines . . . a machine [with] no unnecessary parts.” That is art. That is beauty.

Narrative is not a shallow puddle in which passersby can dally. It is a deep, spellbound lake. It is filled with blood and pain and truth and tanglesome vines. Dip one toe, and you are obligated to swim.

Share This