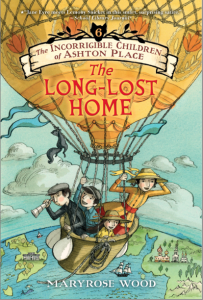

We began our Droplet series on young adult literature with a review of the first book in Maryrose Wood’s series The Incorrigible Children of Ashton Place, so it felt appropriate that she kick-off our interview series as well. We caught up with Wood as she finished the draft of the sixth book in the Incorrigibles series (get a sneak preview of Eliza Wheeler’s cover for book 6 at the bottom of the interview!) to ask about her rambunctious cast of characters, the influence theatre has had on her writing, and the books that inspired her as a child.

RV: To begin, I’m curious – who are your favorite authors? Did you discover any life-altering books as a child (or an adult for that matter), that lead you down the path toward writing books of your own? I’d love to know a bit more about you, and how you happened down the winding path toward authorship.

MRW: When my mom moved out of the house where I spent the second half of my childhood, I became the repository of the Family Stuff. Among the treasures I rediscovered was my battered childhood copy of Bryna and Louis Untermeyer’s Golden Treasury of Children Literature. It’s a great, old-school collection: Kipling, Perrault, the brothers Grimm, Hans Christian Anderson, A. A. Milne, J. M. Barrie, Lewis Carroll, some Tolkien and Charles Dickens and Oscar Wilde, Aesop’s fables and the Arabian Nights.

It’s an old-school list that skews British, as the proverbial “golden age” of children’s literature did, but what the heck. Tolkein, Kipling – you can’t do better at acquiring an ear for language than reading this stuff obsessively as a child, and that’s what I did.

I also had the Untermeyer poetry collection, copyright 1969 edition but it would not be out of place on the Incorrigible children’s nursery bookshelf. Shakespeare! Poe! Coleridge! Longfellow! Blake! It’s all in there. I had forgotten about these books, but in hindsight I realized they were hugely formative. I read all the time as a kid and so ended up rereading whatever books were close at hand till the spines broke, and these two volumes got a workout.

But I didn’t seriously attempt to write fiction until I was in my forties, you know. I was a dramatist before then. I wrote plays, musicals, and screenplays. So all those early influences never got expressed in prose until much later.

RV: The Incorrigible books have an intricately woven and mysterious plot that spans the series – what methods do you use to keep the facts straight? Have things ever started to unravel and required some patch work?

MRW: Honestly, I wish I had a Magic Continuity Elf who was in charge of all this. It’s daunting. I go back and check things all the time. I bought the ebook versions of all the books in the series so I could use the search function to look things up.

Writing The Long-Lost Home has been especially challenging because the die is cast. It’s the sixth and final book in the series; I’ve made my bed of setups, so to speak, and now I have to pay them all off. Much of the big finish has been loosely arranged in my head all along, but when I sit down to execute the narrative tends to want to wander in new directions. I had to be very strict. “Nope! We are staying on track to our destination, no more detours!”

All writing is raveling and unraveling and patch work, in my experience. It’s all a mess until you fix it. Twenty drafts and the first nineteen are not just bad, but terrible, junk. Then you crack it and it’s fine and you can carry on, the will to live restored! It’s important not to abandon things too quickly, or show them to anyone too soon. Nothing works in its early stages: not a paragraph, not a joke, not a plot point. You have to make peace with sitting down each day with this unwieldy beast of a terrible draft and not panic, just tap away at it with your little chisel until it starts to resemble a book. It’s why writers like to stand in the kitchen looking for snacks. Anything to get away from the monster!

All writing is raveling and unraveling and patch work, in my experience. It’s all a mess until you fix it. Twenty drafts and the first nineteen are not just bad, but terrible, junk. Then you crack it and it’s fine and you can carry on, the will to live restored! It’s important not to abandon things too quickly, or show them to anyone too soon. Nothing works in its early stages: not a paragraph, not a joke, not a plot point. You have to make peace with sitting down each day with this unwieldy beast of a terrible draft and not panic, just tap away at it with your little chisel until it starts to resemble a book.

RV: One of my favorite things about your series is that the characters are so lively and vivid – where have you drawn inspiration for your cast of characters? And do you have any favorites?

They come from the land of imaginary people, I suppose! Many aspects of these characters are private homages to characters I love. Penelope has a whiff of Jane Eyre about her, but a whiff of Anne Shirley, too. The Incorrigibles are distant cousins of Curious George and Mowgli. Lord Fredrick has comically bad eyesight like Mr. McGoo. But none of that is planned in a formal way, it’s just what comes out of my personal junk drawer of ideas and influences.

Even so, the characters do feel like real people to me and I’m always curious about what they might do next! I’m an improviser by nature and by training — put the character in a situation and don’t try to control it, just let them react truthfully and see what happens.

Picking a favorite would be like choosing my favorite toe, so I’ll pass on that. I do particularly enjoy writing Lady Constance, though. She’s such a chatterbox that I get to write long monologues for her, which pleases the playwright in me. She’s also the most unintentionally funny character in the series, since there’s a huge gap between how she sees herself and how others see her. Playing with that gap is great fun for a comedy-minded writer.

RV: One more character question; the main character of your series, Penelope Lumley, is both rooted in traditional, Victorian values and presented as a strong, independent female character. She also might be the most steadfast and organized teenager I’ve ever had the pleasure to discover in a book. When you created Penelope, did you see her as a potential role model for girls? Were there any tropes that you wanted to avoid, or to subvert?

I saw Penelope as a true protagonist, the hero of the tale. Fictional heroes tend to be deeply compelling to the sort of person who is moved by heroism, so it doesn’t surprise me that readers find her a positive role model.

There is certainly a lot of play with literary tropes in the Incorrigible Children series as a whole. We’ve got a riff on the Victorian governess novel (i.e., Jane Eyre), the wild child story (The Jungle Book), and even a Pygmalion plot as Penelope teaches the children how to act more human and less wolfish. There are shipwrecks and curses right out of Longfellow and Coleridge, and references to Moby-Dick and Shakespeare. In books 5 and 6 we add the Babushkinovs, a classically unhappy 19th century Russian family. They’ve got a failing beet plantation, unhappy serfs, gambling debts, a dacha they can’t afford…you know, the usual middle-grade stuff!

I’m a firm believer in the definition of children’s literature some wise critic gave to The Hobbit: it’s a children’s book in the sense that the first of many readings over a lifetime can be enjoyed while one is still rather young. I hear from my kid readers enough to know that they revel in all this stuff. Perhaps later they’ll read Bronte and Tolstoy and realize out that there was another layer of allusive comedy going on, but that will be for later. For now, it’s just fun storytelling with a wide world of colorful characters.

“I’m a firm believer in the definition of children’s literature some wise critic gave to The Hobbit: it’s a children’s book in the sense that the first of many readings over a lifetime can be enjoyed while one is still rather young.”

RV: The Incorrigibles are quite wolfish, and many other animal characters have appeared in your books (I’m looking at your, Nutsawoo). If you had to assign yourself an animal that best represented your personality, what would it be?

An owl, perhaps? I tend to be a curious observer, and my day is divided between long periods of sitting still and little bursts of activity. Does that sound owlish? However, I’m not at all nocturnal! Like Miss Penelope Lumley, I prefer early bed-times. I wasn’t always like this, but as the years go by I find I love the early mornings. It’s the best time of day. So I’d be a diurnal owl, if such a thing could exists.

RV: Most writers find it frustrating to have to keep a day job to pay the bills, but the bio in the back of your books seems to imply that you found many of your day jobs inspiring, or at least relatively fruitful. Do you think your experiences doing odd jobs has changed the way you write, or your perspective on your writing? What was your favorite job, and your least favorite?

My favorite non-writing job was being an actor. I realize this is not what most people mean by “day job.” It was my first career. During the years I was an actor I worked a whole range of office temp jobs, though. I typed for a living because in those days typing was a specialized skill that corporations had to hire out-of-work actors to do! The fingers of (mostly male) executives never, ever touched a keyboard.

My least favorite job was at a magazine where my married boss was not so secretly having an affair with a young woman in the office, and the production schedule of the magazine was designed to provide cover for it. Each issue’s production schedule somehow required late nights and weekends in the office, all totally unnecessary. I quit after six months.

The whole concept of “day jobs” and “odd jobs” is provocative and deserves analysis. It’s not a universal law of physics that artists need not be paid a living wage for their work. However, it’s the all too common reality in our culture. Making art, like raising children, is a foundational human activity. We’d still be human beings without hedge funds, but we wouldn’t last long without art and children.

As I say above, I started out as an actor, and professional acting is a union job. I joined the actor’s union at 19 and I learned then that artists are highly trained, highly skilled professionals who perform essential work. We’re entitled to a living wage, benefits, health care, safe and non-discriminatory working conditions and all the rest of the basic rights of a labor force. The current model of artist-as-entrepreneur is a tricky one that works for the outliers and leaves the majority as un- or underpaid hobbyists who make their living elsewhere. It’s not sustainable long term.

Like many writers of a certain age I find myself called to teach writing, a way of passing the torch to the next generation. I’ve taught at undergraduate and graduate-level writing programs and writing conferences, and do private coaching as my schedule permits. I wouldn’t call teaching a “day job” but it has paid all kinds of dividends. I’m surely a better writer for having put myself through the quite difficult task of trying to understand and communicate in a practical way what makes good writing good, and how to apply this understanding to the actual process of drafting and revision.

RV: And, finally: In your opinion, what makes for a good story?

This is the question I seem to be spending this lifetime answering, but I’ll steal a short answer from Joseph Campbell: a good story depicts a hero who, through the experience of trials and revelations, undergoes a transformation of consciousness.

That’s all it is! The rest is taste and craft. I’m a snob about writing craft and can’t get through sloppy prose, it’s too much work. But a well-written tale that does what Mr. Campbell says? That works every time.

About the author:

About the author:

Maryrose Wood is the author of the first five books (so far!) in this series about the Incorrigible children and their governess. These books may be considered works of fiction, which is to say, the true bits and the untrue bits are so thoroughly mixed together that no one should be able to tell the difference. Maryrose’s other qualifications for writing these tales include a scandalous stint as a professional thespian, many years as a private governess to two curious and occasionally rambunctious pupils, and whatever literary insights she may have gleaned from living in close proximity to a clever but disobedient dog.

The sixth book in the Incorrigible Children series is due out in December of 2017. You can pre-order the book here.

Advertisements Share this: