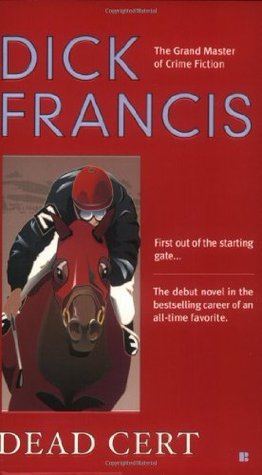

“Dead Cert” wasn’t the first Dick Francis book I read–that honor belongs to “The Danger”–but it’s his first novel in what would turn out to be a long and storied career, so it seems fitting to start my “classics of Dick Francis” retrospective with it.

Reading “Dead Cert” after becoming familiar with Francis’s later works–and I’ve read all Francis’s fictional works, some of them many times–is a bit of an odd experience. It has many of the elements that Francis would go on to turn into a recognizable and influential franchise, but in only semi-finished form: a first-person narrator who is a young-ish, thrill-loving Englishman connected to the world of horse racing; bad deeds sullying the honor of British steeplechasing; a plot, that for all that it is anchored in the rather stuffy, upper-class world of British horseracing, is nonetheless slightly zany, kinky, and off-beat; exciting and unexpected action sequences–Alan York, the hero, has to escape from the bad guys, who are chasing him in radiocar taxis, by galloping off bareback on his champion steeplachaser–and, the thing that holds it all together and transforms it from a rather silly action thriller into a genuine work of literature: a keen awareness of physical and emotional reality.

Indeed, Francis flexes his descriptive muscles in the opening paragraph, which is striking, although, it must be said, flabby in comparison with the bombshell openers of his later works:

“The mingled smells of hot horse and cold river mist filled my nostrils. I could hear only the swish and thud of galloping hooves and the occasional sharp click of horseshoes striking against each other.”

For anyone who has ever ridden a horse in damp weather, the sounds and sensations are unmistakably authentic; for anyone who has not done so, well, that’s what it’s like. Francis had an intense sense of both the outer physical world and the inner emotional world of humans and horses (the horse Admiral is a significant character in “Dead Cert,” as he should be), something that comes across on the pages on this, his first serious attempt at fiction. He knew what it was like to gallop a hot horse on a chill day, and, more importantly, he knew how to convey that to the reader.

In fact, (re)reading Francis right now brings up some interesting thoughts for me, as I wade into the polemics surrounding war literature, a genre that is unique in the jealous guardianship it has by those with first-hand experience of the topic being described. But merely rattling off a series of acronyms or jargon terms, interspersed with cliches about dirt and pain, tends to give the illusion of authentic description rather than the reality of a genuine connection between author and reader. Francis succeeds in conveying the outer and inner worlds of his heroes by his comfortable inhabitance of their society, but also, more importantly, by his understanding of precisely what it would feel like, physically and mentally, to go through what they went through, even when he himself was only guessing. His guesses, though, were always grounded on something real: he may not have lived his heroes’ lives, but he must have known with every fiber of his being what it was to feel pain and fear, and is one of the modern masters of conveying those sensations.

In “Dead Cert” Francis was only just beginning to hit his stride. Alan York is an enjoyable, sympathetic protagonist, but he lacks the damaged depth of Francis’s later heroes, or their terrifying struggles with their own mortality. If Francis had stopped with “Dead Cert,” he would not be the household name he is today. But it’s a good break from the starting gate even so.

Buy links: Barnes and Noble Amazon

Share this: