[Explanation of Reading Journal Entries/Ratings]

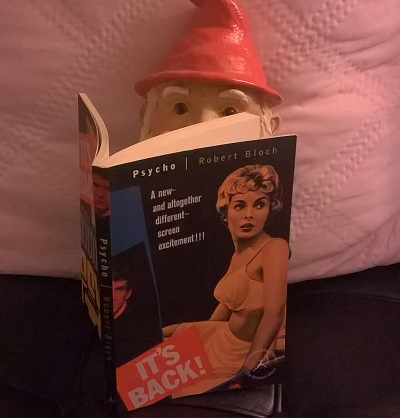

Robert Bloch’s 1959 novel, best remembered as the basis for Hitchcock’s 1960 classic film. I read a British paperback edition.

2 out of 5 stars.

Times Read: 2

Seen the Movie: Original, yes (though it’s been 10+ years); 1998 remake, no.

The Plot:

After stealing $40,000 from her employer, Mary Crane checks into a hotel run by strange, awkward Norman Bates.

At 153 pages this is more novella than novel. It’s a breezy read, handling its dark subject matter as though it was old-hat instead of a kick-off to the sympathetic-serial-killer genre.

I kept thinking of Ian Fleming’s Bond novels while reading Psycho; they have a similar matter-of-fact style and tendency to spend pages on inane inner monologues, each of these one-person conversations ending with the character nodding, shrugging or shaking their head (something I don’t believe many humans actually do while thinking. Let me know if I’m wrong). In a Bond novel I roll with it because they’re dumb and fun and the established world is ridiculous to begin with. In Psycho, I feel like Bloch was filling pages either because (a) He wanted to make the book novel-length or (b) He wasn’t sure what to do with the story and the characters’ thoughts are partly him trying to sort things out, too.

I’m going to lean into (a): Bloch had a great concept for a story, wanted to write a novel out of it, then realized there wasn’t enough meat for a novel. So he padded.

The chapters alternate third-person point of views, so we’ll get Norman’s side of a scene, then in the next chapter Mary (or Lila or Sam) will recount the same events from their point of view. It messes up the rhythm of the story and takes away tension. If Bloch had stuck with one perspective (Norman’s or Mary/Lila), this could have been incredibly tense.

The twist is so tied into pop culture that it’s no more surprising than the killer in Jaws being a shark. If, somehow, someone could read Psycho with absolutely no knowledge of Norman Bates committing the murders, then maybe this would be a fun read.

[1] Reference:

10%

of this book

is dedicated to HARRY ALTSHULER

who did 90% of the work

(dedication page)

Harry Altshuler (1912/1913-1990) was Robert Bloch’s agent. From his New York Times obituary:

Mr. Altshuler, who was born in Philadelphia, joined the Newark Star-Ledger in 1947. He moved to The New York Mirror as a rewrite man in 1955 and later was a feature writer for The World-Telegram and The Sun. At the end of his career, Mr. Altshuler, who was also a literary agent, worked for The National Enquirer and The Globe.

He published a novel in 1968 entitled, “She’s Crazy, You’ll Love Her,” under the pseudonym Joe Bruns.

The book is not listed on Goodreads and there is only one copy for sale on Amazon.

[2] In the book, Norman is an unattractive, overweight man. The movie was onto something by making Norman physically attractive. It makes his turn more of surprise; people were used to using attractiveness to gauge the level of evil in a horror movie. Once in a while you’d get the suave mad scientist or vampire, but usually ugly=evil and beautiful=good.

The book slid from [Norman’s] hands to his ample lap (…) He had lived in this house for all of the forty years of his life.

(p.1)

The light shone down on his plump face, reflected from his rimless glasses, bathed the pinkness of his scalp beneath the thinning sandy hair as he bent his head to resume reading.

(p.2)

[3] References:

The Realm of the Incas, by Victor W. Van Hagen.

(p.2)

Victor Wolfgang von Hagen (1908 – 1985) was an American explorer, archaeological historian, anthropologist, and travel writer who traveled in South America with his wife. Mainly between 1940 and 1965, he published a large number of widely acclaimed books about the ancient people of the Inca, Maya, and Aztecs. Realm of the Incas was published in 1957.

[4] Knowing the twist allows the reader to keep track of the Norma/Norman relationship from the start. I’ll say this for Bloch: he doesn’t cheat. He plants clues to Norman’s madness (and Norma’s death) all over and even tosses in the seemingly offhanded comment that Norman doesn’t like mirrors because his reflection always looks wavy and bizarre (which is why he never “catches” himself in make-up or women’s clothing).

He was aware of the footsteps without even hearing them; long familiarity aided his sense whenever Mother came into the room.

(p.3)

The things she was saying were the things he had told himself over and over again, all through the years.

(p.4)

God, could she read his mind?

(p.7)

He’d given Mother strict orders not to touch anything, and he knew she’d obey. Funny, once it had happened, how she collapsed again. It seemed as if she’d nerve herself up to almost anything – the manic phase, wasn’t that what they called it? – but once it was over, she just wilted, and he had to take over. He told her to go back to her room, and not to show herself at the window, just lie down until he got there.

(p.92)

[5] The prose is functional; not bad but not great (which is better than going for lofty and failing).

She switched off the ignition and waited. All at once she could hear the sullen patter of the rain and sense the sigh of the wind behind it. She remembered the sound, because it had rained like that the day Mom was buried, the day they lowered her into that little rectangle of darkness. And now the darkness was here, rising all around Mary. She was alone in the dark.

(p.19)

Something’s lacking. I can’t put my finger on it (if I could, my own writing would be better) but the characters in this book don’t come alive. Their emotions don’t feel real; I don’t really care what happens to any of them or what they’ve been through.

[6] Mary, for being in a stranger’s home, is awfully bold about giving stern advice. She flat-out says to Norman, without him asking for her opinion:

“How long do you intend to go on this way? You’re a grown man.”

(p.25-26)

[7]

It was the knife that, a moment later, cut off her scream.

And her head.

(p.31)

[8]

You aren’t really a murderer when you’re sick in the head. Anybody knows that.

(p.40)

[9] References:

Ottorino Respighi came into the back room of Fairvale’s only hardware store to play his Brazilian Impressions.

Ottorino Respighi had been dead for many years, and the symphonic group – l’Orchestre des Concertes Colonne – had been conducted in the work many thousands of miles away.

(p.51)

Ottorino Respighi (1879-1936) was an Italian violinist, composer and musicologist, best known for his three orchestral tone poems Fountains of Rome (1916), Pines of Rome (1924), and Roman Festivals (1928). He also wrote several operas. Impressioni Brasiliane (Brazilian Impressions) is a tone poem from 1928.

The Colonne Orchestra is a French symphony orchestra, founded in 1873 by the violinist and conductor Edouard Colonne.

[10] Typo? Should “at” be “as”? Also, idiom?

For the next hour, the table would double in brass at his desk. Just as he would double in brass as his own bookkeeper.

(p.52)

According to the Free Dictionary, “double in brass” means:

To perform multiple roles or duties; to serve in two capacities at a given time. Originally a reference to a musician in an ensemble who plays more than one instrument, especially among brass players.

In the Google books edition of Psycho, the lines reads:

For the next hour, the table would double in brass as his desk. Just as he would double in brass as his own bookkeeper.

So, yes, a typo in my edition.

[11] References:

“I’m trying to recognize that music.” She nodded. “Villa-Lobos?”

“Respighi. Something called Brazilian Impressions. It’s on the Urania label, I believe.”

(p.55)

Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959) was a Brazilian composer. Villa-Lobos has become the best-known South American composer of all time.

There is an Italian classical music record label called Urania, but according to its site, it began in 1998.

According to Discogs.com, Urania Records, Inc is/was located in New York and released classical titles in at least the 1950s.

[12] Lila’s instant deferral to Sam, a man she has just met, is extremely annoying.

Sam glanced at Lila. “What do you think?” he asked.

“I don’t know. I’m so worried now, I can’t think.” She sighed. “Sam, you decide.”

(p.63)

Long before the front door closed behind [Arbogast], Lila was sobbing against Sam’s shoulder.

(p.63)

[13] Investigator Arbogast is a terribly-written character, a walking cliché.

For the first time that evening, Arbogast smiled. It wasn’t the kind of a smile that would ever offer any competition to Mona Lisa, but it was a smile.

(p.63)

I don’t even know what this means. The Mona Lisa is known for having an enigmatic smile. That’s the point. It’s not a good smile. I don’t know how you’d smile less. Is that the joke?

[14]

Once you began speculation about that, once you admitted to yourself that you didn’t really know how another person’s mind operated, then you came up against the ultimate admission – anything was possible.

(p.66)

[15] Reference:

Time is relative, of course. Einstein said so, and he wasn’t the first to discover it – the ancients knew it too, and so did some of the modern mystics like Aleister Crowley and Ouspensky.

(p.76)

P.D. Ouspensky (1878-1947) was a Russian mathematician and esotericist known for his expositions of the early work of the Greek-Armenian teacher of esoteric doctrine George Gurdjieff, whom he met in Moscow in 1915. His book In Search of the Miraculous is a recounting of what he learned from Gurdjieff.

[16] It’s a funny world in Psycho.

Sam waited while [the operator] put the call through.

“Funny,” he said, hanging up. “Nobody answers.” (…)

Lila was waiting for him.

“Well?” she asked.

“Funny. The place was closed up.”

(p.101)

“He wasn’t at the motel when you drove out there?” The question was addressed to Sam and he answered it.

“There was nobody there at all, Sheriff.”

“That’s funny. Damned funny.”

(p.105)

[17]

“Sit still, now. Don’t be alarmed. I’m not alarmed, am I? And I would be if anything was wrong. But nothing is wrong.”

(p.129)

[18] Unless Bloch is trying to make his characters daft, this is not good writing:

The first [door] led to the bathroom. Lila had never seen such a place except in a museum – no, she corrected herself, they don’t have bathroom exhibits in museums.

(p.134)

[19] Reference:

Translations of La’ Bas, Justine.

(p.136)

La-Bas, translated as Down There or The Damned, is a novel by the French writer Joris-Karl Huysmans (1848-1907), first published in 1891. La-Bas deals with the subject of Satanism in contemporary France, and the novel stirred a certain amount of controversy on its first appearance.

[20] While discussing Norman’s motivations and actions, Sam and Lila are very sympathetic and mild about a man who cut the head off of their loved one. Lila:

“And right now, I can’t even hate Bates for what he did. He must have suffered more than any of us. In a way I can almost understand. We’re all not quite as sane as we pretend to be.”

(p.150)

The characters in this book don’t emote, think, or speak in a way that feels realistic in my imagination.

[21]

Some of the write-ups compared it to the Gein affair up north, a few years back.

(p.143)

Most people believe Psycho was loosely based on/inspired by Gein and his inability to give up his dead mother (and desire to be a woman). The story of Gein broke in late 1957 (less than 50 miles from where Bloch was living at the time) and Psycho was published in 1959, so this seems a sound theory.

[22] The narrative seems confused whether Norman’s father is dead or just ran out:

Norman tells Mary:

“My father went away when I was still a baby. Mother took care of me all alone.”

(p.24)

Sam tells Lila:

“I gather Mrs. Bates hated men ever since her husband deserted her and the baby.”

(p.146)

But Sheriff Chambers tells Lila and Sam:

“[Norma] built this motel with a fella name of Considine, Joe Considine. She was a widow, understand, and the talk was that she and Considine were-”

(p.108)

A widow, by definition, has lost her spouse by death. I’ll assume Sheriff Chambers misspoke (or Bloch accidentally contradicted himself).

Hitchcock managed to tease out what was innovative and genuinely creepy in Bloch’s tale but the book itself doesn’t have much to offer.

I’d only recommend it to people interested in screenwriting and film. Like What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? this is a very good example of a screenwriter improving on the source material.

After a Halloween-themed Top 10 on Tuesday, we’ll be starting a four-part look at William March’s short story collection, Trial Balance.

Advertisements Share this: