Latin, Artemisia Absinth. Ancient British, Warmode. Wormwood is a bitter herb with medicinal properties, related to purification and cleansing. Hamlet mumbles its name in Act III, Scene II, during the play he has staged in order to upset King Claudius. The performance faithfully represents the crime of which he believes the latter is guilty. He hopes that the shock—like wormwood—will oblige the villain to vomit. In this case, the truth.

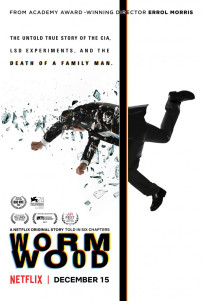

Wormwood1, Errol Morris’ recently released documentary (six episodes, four hours in total), mixes interviews and original footage with reenactments of the main narrative. Those diverse modes are intricately enmeshed, intertwined in a tapestry of great complexity and depth.

The photography of the fictional segments is luscious, with the smooth, brownish light distinctive of nineteen fifties settings. Yet the dominant tone is green, which also colors the room where most interviews take place. Green light peers through the window, refracted by the liquid surface of the table separating Morris from Eric Olson (whom the titles define as a ‘consultant’, but truly is the protagonist). Green—aqua—is the shade of Eric’s eyes, staring straight at the camera as he talks.

*

Eric’s father, Frank Olson, dies on November 28th, 1953, when his son is nine. More precisely he vanishes, leaving for a work-related commitment then failing to come home for Thanksgiving. Crushed while meeting the ground after a thirteen stories flight, his corpse is declared too scattered for his kin to behold.

Frank is a biochemist employed by the CIA. He is involved in research on biological weapons during the Korean War. The extent of his knowledge and responsibility isn’t clear—yet is the key to the mystery of his death.

Earlier in 1953, a wave of ‘confessors’ has made the news. US soldiers—imprisoned and allegedly brainwashed by the communist government—have admitted to massive use of biological weapons in Korea. Once returned to the motherland they have retracted, stating their avowals were false, due to a chemically altered state of mind. The issue is very serious, sets a dangerous precedent, asks for action to be taken.

Therefore, secret experiments are performed on CIA members. They are administered LSD, in order to assess what they might reveal under the influence. Olson undergoes one such test on November 19th. The outcome must be unsatisfying. He is concerned—he says vaguely to his wife—for possible consequences of his poor performance. His boss wants him to see a New York psychiatrist. He is escorted to the session, examined. On his way home—still accompanied—something happens and he is hurried back to N.Y. Trapped in limbo, increasingly preoccupied, perhaps panicked, he communicates with his wife through brief, cryptic phone calls. Then the announcement comes that an accident has occurred. Frank has ‘fallen or jumped’ out of a hotel window.

*

The staged segments lacing the interviews are quintessentially Kafkaesque. They create a nightmarish, oppressive, claustrophobic mood, likely resembling Frank Olson’s reality during his last week. One, two, three, those November days appear on the screen like tabs of a Christmas calendar—little windows hiding each a surprise, an image, a verse. They are opened, peeked in, the picture decoded and the lines spelled out, sometimes orderly, sometimes randomly, as for a knitter backtracking to retrieve a lost loop.

While the feature film tries to flesh out memories—or the lack of—patching up a kind of chronology, the interview scenes of Wormwood are stuck in time. The clock hanging behind Eric Olson displays the same hour from beginning to end. Is it two thirty-two? Thirty-three? That’s when Frank fell or jumped. The absurd immobility of the hands (an easy fix, would it? where did the prop master go?) is subliminally upsetting. So is the spot where the minute hand stays still—between marks, uncertain, unsafe.

*

When news of Frank’s death comes, Eric’s world falls apart. It is not only grief, and its disastrous resonance on a first child identifying with his father. No. The tragedy is amplified by its irrational, inexplicable circumstances. Death inherently tries the human brain, as our mind lacks adequate tools for decoding it. An acceptable narrative, a credible set of reasons, is the minimum that we need to even start mourning. Otherwise reality itself collapses.

A rupture occurs. The boy’s life is ‘sucked into the grave’, trapped by the event, the story, the house that he will be unable to leave. Yet a journey begins, perhaps metaphorical, certainly unavoidable, for him to figure out what happened. He takes it upon himself to unravel the knots, because no one else will do it. Wormwood is the story of Frank’s death and the account of Eric’s quest. Is the place where the two collide.

*

In 1975, an article on the Washington Post causes scandal. It reveals the CIA’s unlawful drug experiments of twenty-two years earlier, culminating with the suicide of an unnamed operative. Details make the victim’s identity unmistakable, therefore the Olson family is hit by another stray bullet. Truth? Hypothesis? Suicide was never mentioned before. Troubled, anguished Frank didn’t talk of drugs on his visit home. This all comes as a novelty. As the family plans on a legal action, the US Government intervenes. Apologies are directly offered by the President—White House, Oval Office. A settlement is agreed upon, in exchange for all claims to be relinquished. The CIA gives the Olsons a bunch of documents—the complete set of files regarding the case.

Far from bringing closure, this development increases confusion, also adding an element of shame. If the accident of the initial announcement didn’t make sense, suicide opens a can of worms. Did LSD destabilize Frank to such an extent? Only in case of a preexisting weak, fragile personality. Did he take his life for other causes? If yes, what?

Once examined, the records provided by the CIA appear to be irrelevant, inconsistent, contradictory and full of omissions. Just a puff of smoke.

*

In the seventies, Eric Olson is a student of psychology at Harvard, focusing on a theory of collage for his thesis. And he makes collages, drawing from huge stacks of cutouts that he assembles in large-scale compositions. For a while he pursues this activity with furious passion, then he lets it wither away together with academia.

In contrast with the compactness of the reenacted segments, interviews and documentary sections of Wormwood employ collage techniques. Morris has always loved them. They perfectly mirror the way our mind scrambles with meaning, making disparate strands of information rub against each other until a spark occurs. Scenes split and multiply in kaleidoscopic fashion. Old family pictures and movies fade in and out, juxtapose, overlap, ripped off or sewn up by kilometers of written lines—clips from papers, magazines, documents, letters. Written words hammering the screen so fast that they are barely readable (therefore asking to be seen again) are also Morris’ signature.

Collage is named after glue, suggesting the impulse of piecing together what was previously torn. But the activity is twofold. Collage artists are first and foremost vandals, scissor-armed, bound to decompose any compact surface offered to their gaze. They are compelled to dismantle it, then create another, more convincing reality. You cannot uncover the truth, says Eric, without destroying all, included yourself. Without questioning everything.

*

Hamlet/Lawrence Olivier appears here and there—a descant, a basso continuo, Eric’s alter ego as he copes with his father’s destiny. What for? Truth? Justice? Revenge? Answers vary and fluctuate. Seeking truth is a leitmotif in Wormwood and throughout Morris’ work—which implies two assumptions. First, the existence of truth. Second, the belief it is worth the price its pursuit demands.

Both points are incessantly stated and challenged, as the narrative keeps defying deciphering—a stubborn Rosetta stone—or dead-ends before a steel wall no human can climb, also doubting the ultimate meaning of finding this craved for Grail. Will it bring contentment? Peace? It doesn’t seem like it.

Eric’s life is swept by a task that his friends call ‘obsession’, eating up his career and loves, causing him to apparently lose himself. He retraces the witnesses of his father’s last days, gets in touch with them all. He spends time in the fated hotel room that has haunted his childhood. Each inquiry brings up some discrepancy, some disturbance confirming that the official reports were just cover-ups. Each discrepancy creates further doubts, further obscurity. Again, is it worth it?

*

Forty years after the fact, in 1993, Eric obtains permission to exhume the remains. It is an important gesture, full of symbolic value. Being denied the opportunity of seeing the corpse had made things more difficult. What is inside that coffin?

Contrary to what had been said, the body is whole and preserved. Even Frank’s penis, his son notices, is recognizable. Is such detail important? Hell yes, that being the organ Frank used to give Eric life, a fact that since the tragic night has turned insubstantial.

There’s no trace of the wounds that crushing a windowpane would provoke. But the skull shows the indent of a blow, suggesting that the man was hit before defenestration. These discoveries match details of a CIA assassination manual, current at the date of Frank’s death, and describing the easiest way to dispose of undesirable agents. The hypothesis of murder arises.

*

A child seeing a masked person isn’t necessarily afraid, as he can imagine the face behind the mask and such expectation reassures him, Eric says. But if the mask, once lifted, reveals another mask, panic and disorientation ensue. Searching for the truth about his father equates peeling off an endless series of disguises. Or—Morris says—the truth of this case is kept in a vault sealed inside a vault, sealed inside a vault. Each step forward makes Eric’s destination recede.

Yet he can’t stop. Truth about one’s father is truth about one’s past, and our past is what places us. We can’t live without situating ourselves in a sort of topography. Loss, confusion and lies about our parents (our origins) literally make us loose footing. There’s no way to go on without first going back—no matter how long the detour.

*

For the following decades, Eric and his lawyers seek further evidence. They also reconstruct the chain of complicities, clearly involving CIA and FBI in connivance with the Government. Frank had found himself in a very uncomfortable spot, due to what he knew of national security and war procedures. He had started to pose a problem, to be a liability. Therefore he had been executed, the homicide then concealed with the agreement of the maximum powers. Sixty years past, it is too late for nailing a culprit, and all has been set for it to be impossible—the responsibility skillfully dispersed, irreducible to a few individuals.

In 2014, Eric contacts journalist Seymour Hersh, who had exposed the LSD experiments in 1975. He explains him his theory and his findings so far. Hersh deems Eric’s reconstruction believable, and one of his trusted sources confirms it. In fact, a top-secret file that the source has accessed contains the entire chronicle of what took place. Hersh, though, can’t betray his informer. Adamantly, he refuses disclosure.

A dead end? Here Morris intervenes and Wormwood begins.

*

What is this all about? ‘It’s about the position in which the US found itself during the post-war period, and wasn’t prepared to face. Democratic institutions were in jeopardy, as they were doing things that people shouldn’t be aware of.’ It’s about concealing misdeeds of enormous impact, loaded with consequences so grave that a few casualties didn’t matter.

If Frank Olson’s fate is a shard of mirror, reflecting a much larger reality, does such knowledge lift a weight? ‘Now you know what happened, but no one else does. The only way the story is bearable, is if it is known.’ Perhaps unofficially, Wormwood fills such gap, giving Eric Olson a way to be heard, and providing for his words a well built, perfectly sound chamber of resonance.

The things he has to say have the thickness, the pondered layering of a lifetime masterwork. They cover a phenomenal spectrum, as he both drills deep into the father/son relationship, dissecting the mechanics of grief, and he spreads in concentric circles, unraveling twist after twist of deception and denial, encompassing ever wider landscapes until a whole page of history is mapped. After all, he has spent decades doing and undoing this Penelope web—this shroud—did he?

*

Was it useless, since achieving a definite result seems impossible? No official amends, no atonement or retribution, no proper re-write, not even some incontrovertible evidence to be put into a frame and hung from a wall.

The whole thing seems to run in circles, therefore leaving the viewer with a sense of frustrating emptiness. “Is it better?” Morris finally asks Eric, hinting at the amount of proofs the latter has gathered, how close he has come to a valid reconstruction. “It is all… bitter,” is the answer. Like wormwood.

It all seems to run in circles, but those loops spiral even so slightly into an arc. Frank, as intimated by the official narratives, is a loser—whatever it means. The man who fell, jumped, or committed suicide, is weak, insane, or both. He has lost something—his mind, discrimination, stability, his love for his relatives, his sense of consequences. ‘Frank Olson couldn’t hold his drug.’ ‘He went down the deep end.’ His failure spills out, swamping and then rotting those whom he has left behind.

Piece by piece, as his son keeps shuttling the thread, tears are mended and stains blotted away. As he digs, Eric finds clear indications that Frank had become a risk not because of his weakness, but because he had grown first uncomfortable, then disapproving of the practices he was aware of and involved with. Seymour Hersh, while refusing to disclose evidence, uses unequivocal terms like ‘dissident’, “detrimental to the war against the USSR’, ‘marching to a different drummer’, ‘dangerous’, and he names a ‘procedure of elimination’.

That a dissident should be eliminated within a democracy is bitter to say the least. But to know about it sweeps shame out of the picture, and puts dignity, courage, integrity in its place.

***

Toti O’Brien is the Italian Accordionist with the Irish Last Name. She was born in Rome then moved to Los Angeles, where she makes a living as a self-employed artist, performing musician, and professional dancer. Her work has most recently appeared in Trampset, Typehouse Magazine, Crux Magazine, and Indiana Voice.

Images: documentarynews.com, spin.com, movieandtvcorner.com

What’s HFR up to? Read our current issue, submit, or write for Heavy Feather.

Advertisements Share this: