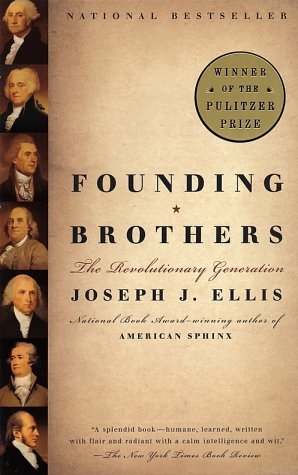

Based on what we now know about the Anglo-American connection in the pre-Revolution era – that is, before it was severed – the initial identification of the colonial population as “Americans” came from English writers who used the term negatively, as a way of referring to a marginal or peripheral population unworthy of equal status with full-blooded Englishmen back at the metropolitan center of the British Empire. The word was uttered and heard as an insult that designated an inferior or subordinate people. The entire thrust of the colonists’ justification for independence was to reject the designation on the grounds that they possessed all the rights of British citizens. And the ultimate source of these rights did no lie in any indigenously American origins, but rather in a transcendent realm of natural rights allegedly shared by all men everywhere. At least at the level of language, then, we need to recover the eighteenth-century context of things and not read back into those years the hallowed meanings they would acquire over the next century. The term American, like the term democrat, began as an epithet, the form referring to an inferior, provincial creature, the latter to one who panders to the crude and mindless whims of the masses.

References: