Deadpool can be quite unlikable.

Often he is supposed to be. Both his ‘subversive’ humour and ‘anti-hero’ status depend upon his separation from mainstream and conventional superheroes, his very being is designed as a contrast to them. However, frequently Deadpool’s aggravation of mainstream Marvel characters becomes an affront against the audience too, his intentionally offensive, crude and annoying behaviour lacking any grand statement, and merely comes across as plainly annoying. The biggest characteristic and greatest flaw of Deadpool is having no stakes. His lack of taste, seriousness or morals has made him a personification of irony, and through recent interpretations especially, Deadpool has become a human cartoon with near-immortality and meta-textual awareness. Cartoons are fine in small doses, but as an actual character it generally leaves Deadpool without a third-dimension. Without cares or concerns, without taking anything seriously, Deadpool holds nothing sacred. And holding nothing sacred means he has nothing to believe in.

Despite his popularity, Deadpool is a difficult character for a regular series. Yet within his 63 issue run, Daniel Way, alongside artist Paco Medina, crafted a seminal story-arc Want You to Want Me (in Deadpool #15-18 (2010)). It combines all the fundamental aspects of Deadpool’s character while delivering an intricate plot. Following Deadpool being marooned on a boat, he makes his way to San Francisco to join the relocated X-Men, a group Deadpool has periodically been associated with. The X-Men are facing their own issues, given during the Marvel Event Dark Reign Norman Osborn (The Green Goblin), having publically executed the Skrull Queen ending Secret Invasion, is the new Director of S.H.I.E.L.D., and is using his new authority to discriminate against mutants. Osborn has funded and enabled Mr Kincaid, father of X-Men member Mercury, to allege they have kidnapped her. Un-expectantly from both parties, when Deadpool tries to audition for the X-Men, he attempts to assassinate Kincaid on their behalf.

Not all is as it seems. A particular element weaved throughout Want You to Want Me is perception versus reality. Despite the various physical fights over Kincaid’s life between the X-Men, Osborn and Deadpool, this is a battle of PR instead of superpowers. How groups are seen to be is more important than how they are. With his obnoxious attitude, vibrant costume and explicit motor-mouth, what Deadpool ‘is’ can seem quite obvious. Yet this story demonstrates Deadpool as a manipulator of both sight and desire, causing people to see what they want to see. Another factor of this story is Deadpool trying to prove himself, the ache for mutual respect evident in the very title. But Deadpool can best operate when the field is uneven, when through misdirection and trickery, Deadpool’s low reputation becomes his best asset.

Deadpool doesn’t want to be unlikeable. He needs to be.

“That’s not even real laughter”; Irreverent HumourPerhaps the most basic necessity of Deadpool is that he be funny. And Want You to Want Me is quite funny, but like much of Deadpool’s comedic style, there is a hint of desperation to it. Samuel Beckett had a thesis of ‘laughing against the dark’, of comedy being a defence-mechanism against life’s existential absurdity. This interpretation of Deadpool’s comedy is surprisingly common, given Wolverine Origins #24 (2008) (which is also quite a poignant Deadpool storyline) has Wolverine commenting upon Deadpool’s “tears of a clown” and X-Men Origins: Deadpool #1 (2010) has Deadpool himself saying life’s choices are “laughter or tears”. Although Want You to Want Me is not this explicit, it begins even more shockingly as there isn’t even a defence-mechanism present. Left to himself Deadpool is quite depressing, his multiple-personalities (in the form of caption boxes) asking Deadpool why they “hurt ourselves” (#15). This opening sequence is a double-entendre between Deadpool’s existential crisis, and his physical need for fish for survival. Metaphors are normally the basis for jokes, a way of avoiding issues, but this instance is used to confront them.

If Sisyphus was Camus’ absurdist hero, able to recognise the absurdity of life and find meaning regardless, perhaps Deadpool is an absurdist anti-hero, aware of the absurdity but refusing to find meaning. Like other Beckett characters, Deadpool’s main goal is finding “ways to avoid boredom” (#15). The danger he undertakes in “fishing” (#15) (hand-to-hand fighting against a Shark) is meaningless due to his “immorality” (#15). Deadpool cannot even anticipate the release of death, and does not crave the essentials of survival. A hallucination has him on a date with the personification of Death, only to disappear when she tells him she is “not real… not to” (#15) him. Unique to Deadpool, what he “need[s] or what [he] want[s]” are not the same thing. Deadpool doesn’t really need anything, not to stay alive at least. Discovering what he wants only becomes more challenging. Comedy in Want You to Want Me is still a defence, but a defence against introspection. Laughter provides brief gratification, but long and deeper rewards require attempting to establish meaning, rather than the cheap and irreverent dismissal that comes with Deadpool’s comedy.

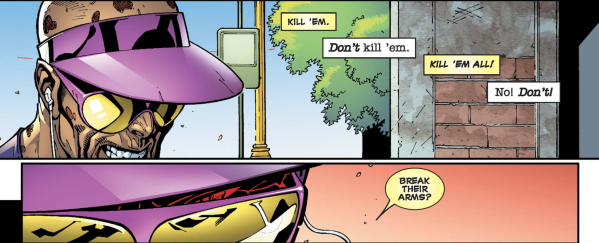

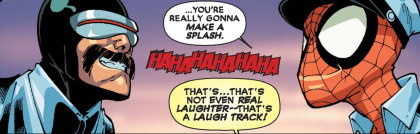

While most of the story’s humour is rather shallow, many of Deadpool’s jokes become quite disturbing if removed from their cartoonish delivery. When the X-Men send Domino (a member having some history with Deadpool) to subdue Deadpool and stop his assassination of Kincaid, she sedates his with “rufies” (#17), causing Deadpool to repeatedly think “don’t be a hallucination” (#17). This joke not only places Deadpool as a (eager) victim of a date-rape drug, but someone whose hopes rest upon it being real, and not “a hallucination” (#17). Deadpool is put under such physical stress in issue #15 that even when swimming to San Francisco he is “still hallucinating a little” given the city is “being attacked by gigantic versions of well-known cereal mascots” (#15). Similar to comedy, hallucinations are an escape from reality, but even they do not give Deadpool full solace, given in these dreams his ‘girlfriend’ (the Marvel personification of) Death is taken away from him by Thanos, and while he is being thrown overboard, Spiderman gets “a laugh track” (#15), causing Deadpool to insist while being tossed “I’m so much funnier than you!” (#15). The core aspect of Deadpool’s identity, his humour, is not his alone. Even in dreams he is outshone. In the absurd, inconsistent world of Deadpool, who cannot even be assured of his humour’s status, the only solution is to laugh harder.

Regardless of Deadpool’s actual inner thoughts, he places deliberate expectation onto others. Generally Deadpool is held with contempt by the mainstream superheroes, the X-Men particularly viewing him as “way too volatile” (#16) to join their organised ranks. His absurdist humour and insane tangents make Deadpool far too unpredictable to be trusted. However, featured in the best Deadpool stories (as I believe Want You to Want Me ranks), there is method behind Deadpool’s madness, an unobserved strategy that is overlooked by the intentional underestimation Deadpool caters for himself. Running on manipulation and misdirection, Deadpool acts like a magician, distracting with his loud and flashy actions so that they are viewed as events in themselves, contained. Making them appear nonsensical allows the actual purpose of Deadpool’s actions to remain unexamined, since their purpose is thought to not exist.

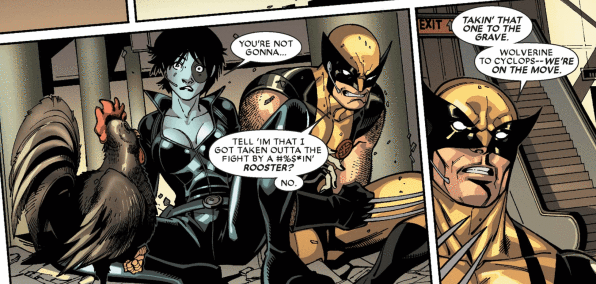

Maintaining the appearance of disorder to disguise Deadpool’s actual plans means they are unpredictable. Upon first seeing Deadpool making “372, 844 pancakes in the morning” (#16), the instinct is to treat it as random absurdity. We join Cyclops’ bewilderment of “what do pancakes have to do with anything?” (#16). Why and how could anybody predict such a thing? Yet Deadpool’s actions are quickly paid-off, since when Domino is first sent to recruit Deadpool for the X-Men (so he will be contained), Deadpool makes her fall through the glass roof, only for the pancakes to break her fall. By causing the perception of harm without actually endangering Domino, Deadpool could discern her true intentions, since if X-Men leader Cyclops “had sent [her] to whack [him], he’d have also sent a back-up crew” (#16) that would’ve arrived during her fall. Later, Deadpool tricks Domino again from the seemingly random and innocuous question of “what’re you scared of?” (#17), which she tells him are “chickens” (#17). When she and Wolverine try to capture Deadpool, she is frozen in the air-vents due to what Deadpool has placed in them, a chicken.

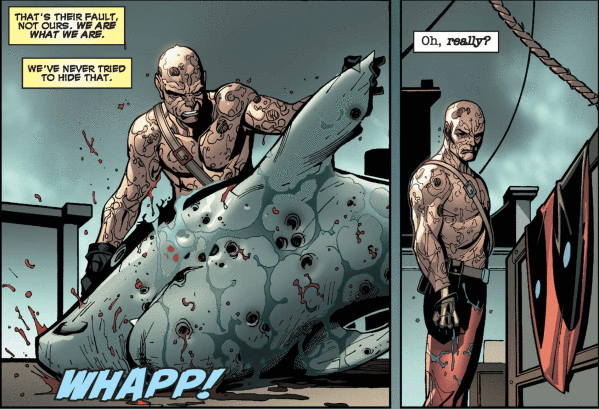

The entire story of Want You to Want Me is a manipulation by Deadpool, conning the X-Men, public and audience. For the majority of plot we assume, like everyone else, that Deadpool actually intends to assassinate Kincaid, thinking him ignorant and simple-minded, unaware of the negative publicity it will bring. Yet as has been revealed, Deadpool is keenly attentive of manipulating perception, and instead “planned every bit” (#18) of his confrontation with the X-Men, including his own defeat and denouncement. Left to itself, the Kincaid situation might “blow over quickly” (#16) as the X-Men expect, but also quietly and unsatisfactorily. By constructing a large spectacle around it, Deadpool intentionally plays the villain for the X-Men, an example of ‘bad mutants’ the X-Men define themselves against and are seen publically defeating. Deadpool gets Kincaid out into the open, but prevents another Sniper hired by Osborn from killing Kincaid, and allowing Wolverine to be publically seen having “saved Kincaid from the Sniper’s bullet” (#18). Fighting the X-Men on camera, Deadpool allows Cyclops to publically reject him, and make the X-Men be viewed as “heroes again” (#18). Furthermore, while Deadpool may have been acting, since he told nobody about this plan, the X-Men were not pretending to stop him or acting like heroes, but would allowed to simply be them. By participating in manipulation and deceit, Deadpool prevents the X-Men from having to do so. While placed into a manufactured situation, the X-Men are given a public forum demonstrate who they authentically are.

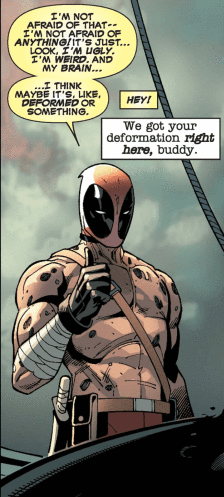

A manipulation of public perception is somewhat inherent to superheroes, who generally rely upon costumes and alter egos, designed to publically present a symbol of themselves while also hiding their true identity. But while Deadpool is indeed not “the only guy running around in a mask” (#15), the X-Men he seeks to impress are not a typical part of the so-called “spandex crowd” (#15). Unlike those whose costumes are designed to protect their secret identities, the X-Men’s are openly known. Indeed such public knowledge is what causes the initial problem with Kincaid and Mercury. The X-Men’s costumes are not secretive but prideful, intending to project their inner uniqueness outwards. Deadpool is hardly proud of his appearance, his insecurities often coming from his aesthetic appearance, blaming his loneliness on the fact “I’m ugly, I’m weird, and my brain…” (#15). How people see Deadpool is limited by what they can see, and Deadpool’s deformed and scarred appearance creates few opportunities for real insight, even if Deadpool would allow it.

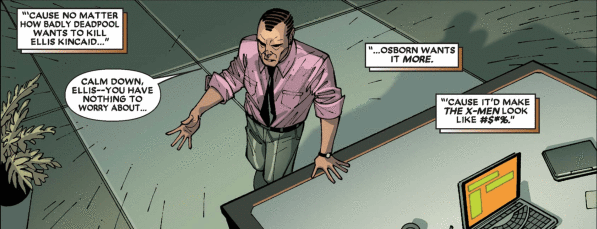

The conflict of Want You to Want Me is a PR problem for the X-Men. Kincaid disavows the X-Men for potentially holding his daughter “against her will” (#16), framing himself as a caring and protective parent, when in reality he was not. Norman Osborn boosts Kincaid’s story to “national coverage” (#16) and subsequently tries to accelerate his assassination by Deadpool to “make the X-Men look bad” (#16), understanding negative publicity helps his anti-mutant authoritative agenda rather than the truth. Osborn is keenly aware of PR manipulations effects, given his rise to prominence in Dark Reign occurred from his televised execution of the Skrull Queen in Secret Invasion. As Cyclops correctly observes, “no matter how badly Deadpool wants to kill Ellis Kincaid, Osborn wants it more” (#17). Both Osborn and the X-Men battle upon a national stage, with cameras constantly reporting their public presence, where their actions are judged not for how they are, but how they look.

The chaotic façade Deadpool employs means his true being cannot be easily perceived. Relying upon deception so much, the Cruise doctor who gives Deadpool medicine is extremely accurate that “there’s no telling what’s going through his head” (#15). Having Deadpool’s intentions remain so unclear means he is inevitably misjudged. He is thrown overboard the Cruise for that “Skrull thing at the Baseball Stadium” (#15), referring to how it appeared like Deadpool betrayed Earth to the Skrulls in Deadpool #1. This remark also connects Want You to Want Me into the larger feud between Deadpool and Osborn. In Deadpool #1, Deadpool infiltrates the Skrull’s spaceship upon Nick Fury’s commands by pretending to betray Earth, in order to steal information on how to kill a Skrull Queen. But when relaying this information back, it was intercepted by Norman Osborn, who then used it to execute her in Secret Invasion’s conclusion. While Osborn manipulated himself through positive PR into a place of authority, Deadpool’s manipulations have earned him a negative reputation. Both are still feeling the effects.

While Osborn is concerned with the way things are seen to be done, to maintain his public image, Deadpool focuses on the results rather than the methods. Deadpool may rely upon his negative reputation for underestimation, but this reputation is not itself the end goal. Of course, the way people are perceived generally effects how they are. Deadpool wears a ludicrous outfit in San Francisco since he “saw it on Television” (#15). This is not presented as inherently bad. When watching Cyclops and the X-Men on TV, Deadpool is persuaded it is “telling [him] what [he’s] supposed to do” (#15), their televised message spreading hope to it’s viewers. In the city, a couple tell the disfigured Deadpool “you’re beautiful sweetie! Don’t let anyone try to convince you otherwise” (#15). This external compliment is internalised quite sincerely by Deadpool. Misinformation and propaganda can be easily spread through the public, but so can kindness and the truth, if it is given the opportunity to be shown.

Few characters are as self-aware as Deadpool. A core aspect of Deadpool is his meta-awareness and fourth-wall breaks, making him able to literally understand his ‘true nature’ as a Comic Book character that other character simply cannot. He knows his vision of Captain America cannot be real since “Ed killed that guy!” (#15), referring to how Ed Brubaker killed off the character. Deadpool and the audience are both aware of his Comic Book nature, and he is characterised so that they are both on an equal level. Deadpool’s schizophrenia is represented through multi-coloured caption boxes, having his inner thoughts projected into the panels, while allowing for Deadpool to self-examine quite easily. The story’s first panel is one caption asking Deadpool “why do we do this?” (#15), making the character’s self-examination and self-awareness prominent and accessible parts of the story.

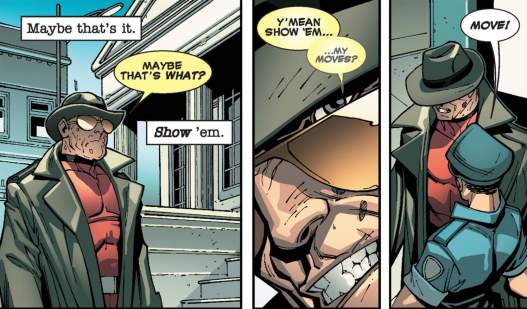

Yet although we might assume such self-awareness would make Deadpool a transparent and unfiltered character, the knowledge of a continually watching audience makes Deadpool always performing. While acting irreverent, Deadpool craves appreciation and validation “from whomever is paying attention” (#15). Deadpool is trapped, in that his methods require misjudgement and negative publicity, but he desires approval for skilfully using these methods. He desires to be seen for an invisible art. Deadpool is prompted into action by wishing to “show [the X-Men his] moves” (#16) and make Cyclops “to see what [he] can do” (#16). The focus here is again on perception, on show and sight, and while we assume Deadpool’s “moves” (#16) refer to his assassination skills, they actually refer to his manipulation of PR. Deadpool admits “I don’t like being judged” (#15), but this is because Deadpool’s techniques rely upon being judged poorly. Perhaps there is some truth behind Deadpool’s declaration that “Cows scare the *#$% outta me!” since “all they do [is] stare at you. Waiting” (#17). The unending observance and judgement Deadpool faces from the Comic Book audience is already enough for him.

Although Deadpool is angered from the X-Men’s rejection, it is hardly surprising. Although there are frequent comparisons made between Deadpool and the “checkered past” of “a guy like Wolverine” (#16), Deadpool and Wolverine are different breeds of ‘anti-hero’. Wolverine may struggle to adhere to a team environment and moral code, but his character is informed by this struggle, the difficulties in changing his ways. Meanwhile Deadpool is characterised by having no moral code, from no potential of joining a team, and being a subversion of the traditional heroes. While Wolverine may struggle to fit in, his membership is one of overcoming adversary. Deadpool’s adversity cannot be overcome. He is an outsider, whose identity comes from defining himself against what the mainstream is, meaning he can never become a part of it.

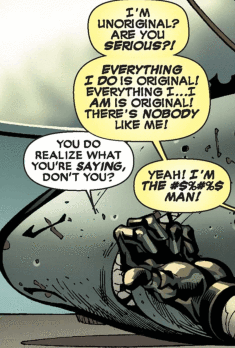

Isolated on a boat in issue #15, this outsider status seems quite pointless without the mainstream counterparts. Deadpool tries to assert “everything I do is original. Everything I… I am is original. There’s nobody like me!” (#15), but basing his identity around uniqueness is only isolating for Deadpool. With there being “nobody like” (#15) Deadpool, all that he really is, “is alone” (#15). At Want You to Want Me’s beginning, Deadpool feels trapped in this lonely identity, unable to “be anything other than what” (#15) he is. But through the story Deadpool is able to rejuvenate his self-conception, not by changing his identity, but by reaffirming its necessity.

In the story Deadpool’s unconventional status gains purpose by reaffirming the nature of conventional heroics. When Cyclops publicly (and sincerely) declares to Deadpool “you are not. You never were. And you will never be an X-Man” (#18), Deadpool might be forever excluded from that particular group (ignoring the fact Deadpool later became part of the X-Force team), but his identity has been reaffirmed by negation, by being “not” (#18) an X-Man. Through pretending to be a ‘bad X-Man’, someone they needed to defeat and denounce, Deadpool was able to define himself against a collective instead of inside it. He could “show” (#16) them what he can really do by ‘showing them’ what he isn’t.

Maybe fittingly for a Deadpool story, Want You to Want Me is not perfect. But Deadpool is also defined by imperfections. Despite the set-up and complexities of Deadpool’s plan, the conclusion after the reveal is only a page long. He receives “no thanks” (#18) or resolution from the X-Men, only being shuttled off from San Francisco to New York. Now more than ever, he and the X-Men are simply incompatible. Such a vigorous rejection after risking so much to help the X-Men might be harsh, but it’s also “reality” (#18). It is unavoidable. But while Deadpool may be defined as separate from the X-Men, he can still be recognised by them. His identities worth is both confirmed and reciprocated. Validation is what Deadpool has been seeking in this story, and finally, after such manipulations and misconceptions, Deadpool is not only seen but also acknowledged.

It may not be what Deadpool wants, or what he needs. But it’s the reality he has.

Deadpool: Want You to Want Me is comprised of Deadpool (2008) #15-18, written by Daniel Way, with art by Paco Medina, colours by Marte Gracia and Antonio Fabela, and inked by Juan Vlasco. The storyline can be purchased here.

Advertisements Share this: