When Eleanor Parker left her Warner Bros. contract in early 1950, she did so before any of her films of that year released. There were three–Chain Lightning, Caged, and Three Secrets. All three were successful. She was top-billed on the latter two (and second-billed only to Bogart in Lightning). She’d get an Oscar-nomination for Warner’s Caged, only she wasn’t Warner’s star anymore. Parker was going into the early fifties a free agent; nine years into her career, she was finally going to be able to pick roles, not have them assigned and have to refuse them until she got good ones.

Parker’s comeback year of 1950 had been a financial success in addition to critical. She didn’t have any releases in 1949 and the films where she was top-billed (Caged and Three Secrets) did better box office than her pairing with Bogie in Chain Lightning. She had received her first Oscar nomination for Caged, where she was top-billed pretty much by herself, and it was the biggest hit of the three. She would be just as busy as a free agent, with three 1951 releases.

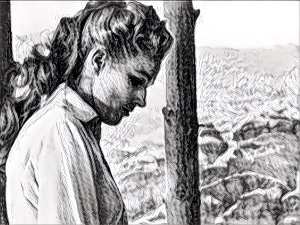

Anthony Dexter is Rudolph Valentino and Parker is not Agnes Ayres in VALENTINO.

Anthony Dexter is Rudolph Valentino and Parker is not Agnes Ayres in VALENTINO.

Parker’s first film of 1951 was a Technicolor biopic for Columbia, Valentino. Directed by Lewis Allen, the film had been in development hell since the late 1930s. Producer Edward Small just couldn’t get it made. When he finally did, it was with unknown Anthony Dexter in the title role. Parker is top-billed, however, as a (fictional) silent era superstar. Third-billed Richard Carlson is the director who loves Parker but knows Dexter is the superstar waiting to happen. Joseph Calleia plays Dexter’s sidekick. Patricia Medina is there to give Parker and Dexter a second love triangle (in addition to the Parker-Dexter-Carlson one).

Valentino (1951). ⓏⒺⓇⓄ. 2017 review

Valentino (1951). ⓏⒺⓇⓄ. 2017 review

Valentino is a terrible film. Dexter can’t act, but even if he could, George Bruce’s script is terrible. Even if the script weren’t terrible, Allen’s direction is bad. Even if Allen’s direction wasn’t bad, the budget would be a problem. Thankfully, they don’t cheap on Parker’s glamorous wardrobe, but everything else is desperately cheap. Well, not the Technicolor. The Technicolor is something–and it’s Parker’s first time in a color picture since her Warner Bros. short subjects in 1942. She does what she can in Valentino, to some success in the first act when she’s the lead, but there’s only so much she can do.

VALENTINO: The faux Great Lover and Parker.

VALENTINO: The faux Great Lover and Parker.

When the film came out in March 1951–three weeks before Parker didn’t win Best Actress for Caged at the Oscars–Valentino bombed with audiences and critics alike. Dexter, ostensibly primed for Hollywood stardom, did not get his second role for Columbia and producer Small–they were all going to remake The Sheik. Small managed to hang on at Columbia (Valentino had been his first film in a two year contract) for ten more films. Intentionally or not, Parker never appeared in another Columbia Pictures theatrical release (though she would do some TV work for them in the seventies and eighties). Silent screen star Alice Terry (who was part of Parker’s amalgam character) sued, Valentino’s siblings sued–Columbia settled out of court. The film’s never been released on home video in any format, which is no great loss. Other than it being Parker’s first Technicolor feature–with technically superior photography from Harry Stradling Sr.–and for her having a phenomenal wardrobe.

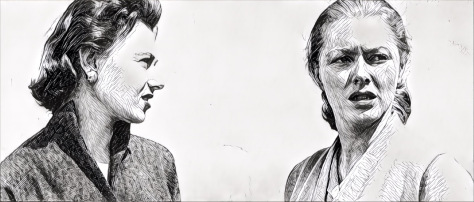

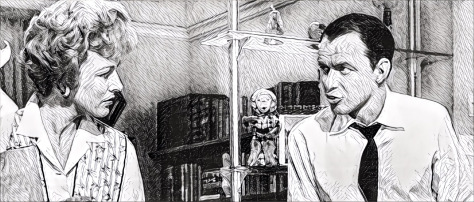

Millionaire (MacMurray) meet Christy (Parker) in A MILLIONAIRE FOR CHRISTY.

Millionaire (MacMurray) meet Christy (Parker) in A MILLIONAIRE FOR CHRISTY.

Parker’s next film, A Millionaire for Christy, came out in September. Produced by Parker’s then husband Bert E. Friedlob, Christy is a screwball comedy with Parker as legal secretary out to marry–you guessed it–a millionaire. Fred MacMurray is the millionaire in question, though he’s already engaged. Chaos and comedy ensue, with Kay Buckley and Richard Carlson along for the ride. In addition to Carlson, the Valentino mini-reunion includes Harry Stradling again photographing–though this time in black and white. Carlson’s stuck in a love triangle again, but not involving Parker–Buckley’s thrown him over to marry MacMurray. George Marshall directs the film, Parker’s first (and only) 20th Century Fox release of the fifties.

A Millionaire for Christy (1951). ★★. 2007 review

A Millionaire for Christy (1951). ★★. 2007 review

Christy’s first half hour isn’t impressive–instead of doing a new screwball comedy, the first third of the ninety-minute film recycles old screwball tropes. After the thirty minute mark, however, Christy immediately improves, all thanks to leads Parker, Carlson, and MacMurray. Director Marshall has problems throughout; Christy occasionally will come off like violent film noir, not madcap comedy. A lot of the action takes place on location at the Marion Davies Beach House in Santa Monica and Marshall just can’t seem to figure out how to shoot there. Parker and MacMurray’s chemistry (eventually) helps a lot. MacMurray’s best opposite Parker (versus his own subplots) and Parker’s awesome (after that first third). Plus Carlson. Carlson gets a far better material than in his last outing with Parker. Still, the problems weigh the film.

A MILLIONAIRE FOR CHRISTY: Parker spins a tale for MacMurray and Buckley.

A MILLIONAIRE FOR CHRISTY: Parker spins a tale for MacMurray and Buckley.

Contemporary critics greeted the film with muted praise–though Louella Parsons chose Parker’s performance as the “Best of the Month” for her Cosmopolitan column, surprised (and delighted) to see Parker so ably toggle from drama to comedy. The film had some behind the scenes drama–with Friedlob apparently not paying MacMurray or Parker on time, then turning around and selling television rights without getting the cast royalties (despite being married to Friedlob another two years, Parker never made another film for him)–and there were some cuts made to the film. Maybe they’d have helped, maybe not. Audiences weren’t particularly warm to Christy either; it was less successful at the box office than Valentino. Christy never had a VHS release, but did air on television. Hopefully with residuals being paid. Warner Archive has released the film on DVD and it’s available streaming as well. So Christy isn’t hard to see and is more than worth a look for one of Parker’s rare(ish) comedic roles.

Parker in DETECTIVE STORY.

Parker in DETECTIVE STORY.

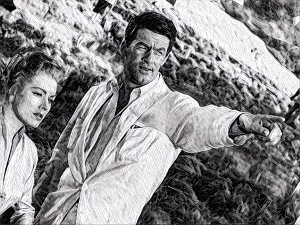

She returned to drama just under two months later with William Wyler’s Detective Story. Earlier in the year (before Valentino came out), Parker had signed a non-exclusive, one picture a year contract with Paramount. Detective Story was her first role for them. Based on the play by Pulitzer Prize winner Sidney Kingsley, the film stars Kirk Douglas as a hard boiled New York cop who has a very bad day. Parker’s his wife and the one bright spot in his life. William Bendix plays his partner. Story takes place almost entirely in Douglas and Bendix’s police precinct, with an assorted cast of characters–ranging from first-time shoplifter Lee Grant to career burglar Joseph Wiseman to abortionist George Macready–populating. Robert Wyler and Philip Yordan adapted the play.

Detective Story (1951). ★★★★. 2016 review

Detective Story (1951). ★★★★. 2016 review

Detective Story is a truly outstanding motion picture. Before even getting to the acting, there’s Wyler’s direction. He takes the play adaptation very seriously, using the film medium to inspect the play and its characters as their day unfolds. It’s stunningly produced. And now the acting. Parker gets the best part, she’s the subject of the film (without knowing it) and the only one who can tame Douglas’s savage beast. Douglas is a fantastic combination of terrifying and reassuring. The acting is spectacular all around, with Wyler purposefully showcasing his cast’s abilities. Detective Story–and its cast–spellbind.

DETECTIVE STORY: Douglas and Parker.

DETECTIVE STORY: Douglas and Parker.

The film got excellent reviews on release–though New York Times critic Bosley Crowther (wrongly, quite frankly) wasn’t impressed with Parker. The Academy disagreed with Crowther (because he’s so outrageously wrong), nominating Parker for Best Actress (a year after her nomination for Caged); the film got three more Oscar nominations–direction, writing, and supporting actress (Lee Grant). It didn’t win any, though Grant did win Best Actress at Cannes. Three years later, Douglas and Parker would reunite for the Lux Radio adaptation. Detective Story never had a VHS release–though the film’s strong reputation never lessened between its theatrical release and, finally, its DVD release in 2005. Paramount was never good at getting its classics out on home video, so the film’s occasional television airings were notable events. While the DVD has gone out of print, the film’s available streaming. Thank goodness.

Parker as Lenore in SCARAMOUCHE.

Parker as Lenore in SCARAMOUCHE.

Seven months after Detective Story, in June 1952, Parker would return to screens–in color again–in MGM’s Scaramouche. The film’s a pre-French Revolution Technicolor adventure epic with Stewart Granger as a swashbuckler who occasionally acts with a traveling troupe. The film’s based on Rafael Sabatini’s 1921 novel, which Metro had successfully adapted at the time, making the film Parker’s fourth remake. Parker’s the glamorous, gorgeous female lead in the troupe and Granger’s lover; though they’re frequently on the outs due to his 18th century French male bullshit. Janet Leigh plays noble bastard Granger’s half-sister; he has to protect her from villain (and vicious swordsman) Mel Ferrer. Aristocrat Ferrer’s out to destroy the burgeoning revolutionaries–pragmatically murdering them–but he’s also trying to marry Leigh. George Sidney directs, Charles Rosher photographs the resplendent Technicolor.

Scaramouche (1952). ★★★★. 2014 review

Scaramouche (1952). ★★★★. 2014 review

Scaramouche is a thrilling delight. It’s deliberately plotted, introducing top-billed stars Granger and Parker after Leigh and Ferrer, with director Sidney carefully guiding viewers through the film. While a swashbuckling adventure (with a lot of comedy), Scaramouche also has a lot of story; it needs time to set up its location and its characters for the impending revolution. Lots of inherent (and implied) ground situation before the film gets to introducing Granger (much less Parker). Parker’s luminous, something she enthusiastically incorporates into her performance, and she and Granger are wonderful together. That chemistry is a testament to her professionalism–many years later she revealed Granger was the only costar she couldn’t stand (though few could stand Granger, apparently). Granger, regardless of his off-screen demeanor, is great. Ferrer’s a truly vile bad guy–he and Granger have either the longest or one of the longest film sword fights. Leigh’s good. Everything’s good in Scaramouche.

SCARAMOUCHE: Chemistry abound from Parker and Granger.

SCARAMOUCHE: Chemistry abound from Parker and Granger.

And Scaramouche was a big hit, with both audiences and critics. Bosley Crowther, in the New York Times, was thrilled with Parker in this one. As was MGM–they signed her to a five-year contract just after the film’s release (they already had her next film in the can). The film got its first home video release in the late 1980s with a Criterion Collection LaserDisc; MGM got it out on VHS a few years later. Warner released a DVD in 2003–Scaramouche has always been one of Parker’s most accessible films–and Warner Archive has since put it back out. It’s also available streaming. Despite all those releases and its constant availability (TCM also airs the film), Scaramouche seems to have something of a muted reputation these days. Or maybe it just doesn’t have its deserved, ever-present boisterous one.

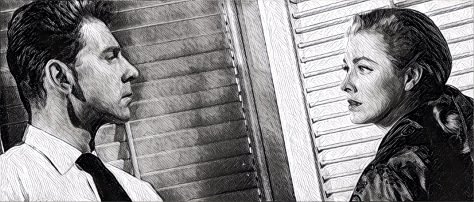

Not many smiles for Taylor and Parker in ABOVE AND BEYOND.

Not many smiles for Taylor and Parker in ABOVE AND BEYOND.

Parker’s next film for MGM, Above and Beyond, arrived right after New Year’s Day 1953 (though its premiere was on New Year’s Eve 1952). The black and white film, directed by Melvin Frank and Norman Panama, tells the true-ish story of Paul Tibbets (Robert Taylor), pilot of the Enola Gay–which dropped the Hiroshima bomb–often from the perspective of wife Parker. Much of the film involves the couple’s marital tensions, brought on by Taylor’s secretiveness and the general strain of living on an airbase during a top secret project. Second-billed Parker narrates the film, scripted by Beirne Lay Jr. and the directors. James Whitmore plays the calming base security officer, who ends up Parker’s confidant. Sort of. Alongside Parker’s story line is Taylor’s, from the Manhattan Project to the decision to drop the bomb.

Above and Beyond (1952). ★★★★. 2011 review

Above and Beyond (1952). ★★★★. 2011 review

Above and Beyond is outstanding drama. The filmmakers give Parker a lot more to do scene-to-scene, but Taylor ends up with the better part. He’s got weight of the world on his shoulders and can’t express its toil externally. It’s got to simmer throughout the entire picture–Parker’s absent from the screen at times (though present through the narration), but Taylor’s almost always there. Frank and Panama go through the historical material matter-of-fact. There’s a lot of history procedural, meaning the somewhat rare scenes between Parker and Taylor–usually she’s homemaking alone and he’s doing his secret Manhattan Project stuff–their scenes together have to succeed (as their relationship is the whole point of the film). And their scenes do succeed. They’re always fantastic; the actors and their scenes. Frank and Panama get it.

ABOVE AND BEYOND: Still no smiles.

ABOVE AND BEYOND: Still no smiles.

Contemporary critics were lukewarm to Above and Beyond overall, usually liking Taylor and the military stuff, not so much Parker or the marriage drama. The film did well at the box office and made the National Board of Review’s ten best list for 1952 (meaning it made the list before its general theatrical release). Parker and Taylor’s chemistry was so successful they went on to make two more films together at MGM. Above and Beyond came out on VHS in the mid-nineties, aired on Turner Classic Movies, and was in the initial batch of Warner Archive’s DVD releases. It’s now also available streaming. While readily available over the years, it’s rarely gotten much attention, which is unfortunate. It ought to be seen.

South and North collide. Parker and Holden in ESCAPE FROM FORT BRAVO.

South and North collide. Parker and Holden in ESCAPE FROM FORT BRAVO.

It would almost be New Year’s again before Parker’s next film arrived. Released in December 1953, Escape from Fort Bravo–in Anscocolor–is Parker’s first Western. While she shot scenes for They Died with Their Boots On as her first Warner Bros. assignment in 1941, they ended up on the cutting room floor. Fort Bravo is a Civil War Western, set in a Union prison camp; William Holden is the ruthless captain, Parker is the fetching Confederate spy, John Forsythe is the imprisoned rebel commander. The action changes from prison break to Native American siege. Holden and Parker’s romantic feelings for one another complicate matters. John Sturges directs, William Demarest and William Campbell costar.

Escape from Fort Bravo (1953). ★★★★. 2005 review

Escape from Fort Bravo (1953). ★★★★. 2005 review

Fort Bravo is speedy, excellent Western. Holden’s outstanding, juxtaposed against alter ego Forsythe, with both men fighting over Parker. Parker plays her part quite well–once everyone’s under siege, she has less dramatic work (at least as far as her reluctant but all-consuming romance with Holden)–with Sturges keeping everything moving. The film’s nimble in both its action and romance thanks to Frank Fenton’s screenplay; Parker gets enough personality to hold her own against Holden. Fort Bravo’s got great production values, beautiful Robert Surtees photography, and fine (or better) performances.

Parker and Holden are all smiles before the ESCAPE FROM FORT BRAVO.

Parker and Holden are all smiles before the ESCAPE FROM FORT BRAVO.

Critics didn’t have an agreed consensus on Escape from Fort Bravo. New York Times critic Howard Thompson had little use for the actors’ performances save Holden; his observations of Parker’s contributions were pure objectification. Time Magazine did like the film, however. And it was a box office hit. Fort Bravo was also MGM’s first time doing their own wide-screen process (Bravo had initially been intended for 3D but, alas, that craze had passed before filming began). Fort Bravo came out on video in the late nineties and it aired on Turner Classic Movies. When Warner released the DVD in 2008, Fort Bravo got its first widescreen home video release. It’s now available streaming as well. Like most pre-sixties, non-revisionist Westerns, Fort Bravo seems to have been forgotten, which is too bad. Parker had intentionally avoided the genre while under contract at Warner in the forties; she waited for a good one.

Eleanor Parker is Mrs. Leiningen in THE NAKED JUNGLE.

Eleanor Parker is Mrs. Leiningen in THE NAKED JUNGLE.

It was back to Paramount for Parker’s next picture, The Naked Jungle, which came out in March 1954. Top-billed–over rising “action hero” Charlton Heston–Parker plays a mail order bride who gets more than she bargained for when she arrives at Heston’s South American cocoa plantation. Rugged, cold, socially inept, and now super-rich (the film takes place in 1901), Heston wants a demure, submissive wife. Parker’s anything but. While they’re waging marital warfare, a bunch of killer ants attack. Directed by Byron Haskin and produced by George Pal, Naked Jungle starts a romantic drama and ends up a large-scale action thriller. The film’s based on Carl Stephenson’s short story, Leiningen Versus the Ants, which had a very successful radio adaptation in the late forties. William Conrad, who voiced the Heston part on radio, costars in the film.

The Naked Jungle (1954). ★★★½. 2015 review

The Naked Jungle (1954). ★★★½. 2015 review

The Naked Jungle is fantastic. Haskin’s not the best director for the drama or the action, but he’s solid and can execute the film’s phenomenal special effects. Parker’s performance is great, with the screenplay giving her a whole lot to do. Her character isn’t in the source material so the great writing is all screenwriters Ben Maddow and Ranald MacDougall (Philip Yordan, who co-adapted Detective Story, fronts for Maddow in the credits). The film takes its time working through the relationship problems with Heston and Parker before getting to the ants. Drama then action. It all hinges on Parker though. Without her, it’s a fine action movie. With her, it’s this strange, wonderful genre period picture. One gorgeously photographed in Technicolor by Ernest Laszlo.

THE NAKED JUNGLE: Parker has Heston (justifiably) starry-eyed, whether he likes it or not.

THE NAKED JUNGLE: Parker has Heston (justifiably) starry-eyed, whether he likes it or not.

The film was a solid hit on release and well-reviewed (at least by Bosley Crowther at The New York Times). It was, however, Parker’s last (and only second) film under her non-exclusive Paramount contract. The Paramount home video division got Naked Jungle out fairly early, releasing the film on VHS and LaserDisc in the late eighties. They got it out on DVD in the mid-aughts; they eventually did let it go out of print, with Warner Archive taking over distribution of the film for a while. Both releases are now out of print, but the film is still available streaming. Naked Jungle has never seemed to have had much modern awareness or appreciation, even though it’s been readily accessible for much of the home video era.

VALLEY OF THE KINGS: Tomb raiding reunites Parker and Taylor.

VALLEY OF THE KINGS: Tomb raiding reunites Parker and Taylor.

Parker’s next film–back at MGM–was another period adventure. Valley of the Kings came out summer 1954, reuniting Parker with Taylor in the story of rival archeologists out to loot as much Egyptian treasure as they can. Sort of. Taylor’s the good guy archeologist, Carlos Thompson is the bad guy archeologist. Thompson’s married to Parker, but if the billings are any indication (Thompson’s third-billed, the font half the size of Taylor and Parker’s), there might be some romance brewing for Taylor and Parker. Robert Pirosh directed the film, which shot (some) on location in Egypt–with great Robert Surtees photography; Pirosh also co-wrote the script with Karl Tunberg.

Valley of the Kings (1954). ★. 2006 review

Valley of the Kings (1954). ★. 2006 review

Valley of the Kings is not a good movie. It manages to be too short but still boring. The script is bad, the direction is bad. It’s pretty enough, with Surtees Eastmancolor, but the film is a substantial letdown given it reunites Parker and Taylor. Taylor’s excellent, which is its own achievement given the inconsistency of the script. Parker, unfortunately, gets done in by that inconsistency–the script significantly changes her character in the third act and then manages to make things worse as the film wraps up. Thompson is awful. Kings’s second half rallies quite a bit, but nowhere near enough to save the film.

KINGS: Parker and Taylor on location.

KINGS: Parker and Taylor on location.

Contemporary critics liked the Egyptian location shooting–Valley of the Kings was one of the first major Hollywood productions to film there (first or third, depending on the source)–but stayed mum on the rest. A.H. Weiler, writing for The New York Times, indifferently spoils the film’s ending while enthusiastically complimenting the visuals. Audiences apparently didn’t want to see the Egyptian locales enough to flock to theaters; Valley of the Kings didn’t make its money back, even with better foreign grosses than domestic. It cost way too much for a ninety minute trifle. The difficult filming experience did encourage Pirosh to give up the director’s chair, so at least some good came out of it. MGM put the film out on VHS in the mid-nineties; Warner Archive got a DVD release out twenty years later. Turner Classic Movies aired it in the interim, which is both good and bad. You want Parker’s films to be accessible, but not so much Valley of the Kings. The film ruins Parker’s streak of excellent films starting with Detective Story, after all. And utterly wastes one of her three pairings with Taylor.

MANY RIVERS TO CROSS: Parker and proud pa McLaglen.

MANY RIVERS TO CROSS: Parker and proud pa McLaglen.

That last pairing would be Many Rivers to Cross, Parker’s first of three 1955 releases; Many Rivers came out in February, a Frontier romantic comedy. Parker’s a frontier woman who sets her sights on trapper Taylor. Hilarity, high jinks, and Frontier intrigue ensue, often involving Parker’s family. Victor McLaglen plays her father; she’s got four protective brothers–though Parker can handle herself–and a suitor (Alan Hale Jr.) she’s not interested in. Taylor’s trapper is just passing through; he’s not the marrying kind. Parker’s going to change his mind. Roy Rowland directs.

Many Rivers to Cross (1955). ★★. 2007 review

Many Rivers to Cross (1955). ★★. 2007 review

Besides being a Parker and Taylor pairing (and their last), having two “Gilligan’s Island” cast members (in addition to “Skipper” Hale, “Professor” Russell Johnson plays one of Parker’s brothers), and some gross racism against Native Americans, there’s not a lot to distinguish Many Rivers to Cross. The acting’s solid all around and it’s fun to see Parker in this kind of role. It’s just nowhere near as impressive as it ought to be, certainly not as Parker’s first CinemaScope outing.

Parker displays her flirting style on Taylor.

Parker displays her flirting style on Taylor.

While MGM didn’t have much faith in Many Rivers to Cross–releasing it on a double-bill by the time it got to New York City–the film turned a profit at the box office. New York Times critic Howard Thompson didn’t have many compliments–not even for Parker’s appearance this time; he much preferred the other half of the bill, The Pirates of Tripoli. The Variety critic wasn’t particularly impressed either–though they were a tad nicer about Rivers than Thompson. The film never had a VHS release, no doubt saving it from some terrible pan-and-scanning; it did air on Turner Classic Movies. It got something of a hidden gem reputation–Parker as a frontier woman, Taylor as her romantic prey, how could it not. Warner Home Video put it out in the late aughts, so at least it’s accessible now. It’s also available streaming. But an inglorious conclusion for the Parker and Taylor trilogy (though still a marked improvement over Valley of the Kings) and not the best start to Parker’s 1955 releases.

Parker and Ford in INTERRUPTED MELODY.

Parker and Ford in INTERRUPTED MELODY.

Five months later, MGM released Parker’s next film, Interrupted Melody, in Technicolor and CinemaScope. Directed by Curtis Bernhardt and produced by Jack Cummings (who also produced Many Rivers–Parker stormed his office to convince him she was right for Melody), the film adapts Australian soprano Marjorie Lawrence’s life story, specifically her battle with polio, which paralyzed her at the height of her career. Parker plays Lawrence, Glenn Ford plays her husband. Young Roger Moore shows up for a bit as Parker’s brother, but the film is really Parker and Ford’s show. American soprano Eileen Farrell (uncredited) does the singing for Parker; on set, however, opera novice Parker “screamed” the songs (according to Cummings), which led to the film’s remarkable lip-syncing.

Interrupted Melody (1955). ★★★★. 2006 review

Interrupted Melody (1955). ★★★★. 2006 review

Interrupted Melody is a contender for Parker’s finest lead performance. The film–fueled by William Ludwig and Sonya Levien’s script–toggles between her and Ford, so it’s good Ford is excellent as well. It’s an outstanding production–the scale of the opera houses, the diva costumes, Joseph Ruttenberg and Paul Vogel’s gorgeous color photography. At the center of it all is Parker, who’s got a lot to do. She’s the outward facing character, Ford’s the inward. Bernhardt’s direction is agile–the operas, the romance, the polio treatments, the rocky marriage–and always good. Parker’s performance in Interrupted Melody was her favorite and for good reason.

INTERRUPTED MELODY: Ford and Parker.

INTERRUPTED MELODY: Ford and Parker.

Interrupted Melody was a hit on release, both with audiences and critics. Bosley Crowther at the New York Times was a big fan of the film (pretty much saying the same as above, only with some complaints about CinemaScope framing). The film received three Academy Award nominations–Best Actress, Best Writing, and Best Costume Design. Ludwig and Levien won for their script. Melody would be Parker’s final Oscar nomination. MGM/UA put Melody out on VHS in the mid-nineties, following it up with an LaserDisc release a few years later. The LaserDisc was letterboxed, preserving the beautiful CinemaScope frame Crowther didn’t like. Turner Classic Movies regularly aired the film. Warner Archive got the DVD release out in 2009. It’s also now available streaming. Interrupted Melody is “the” Eleanor Parker film from her MGM period; it’s a shame she wasn’t top-billed. No slight to Ford, but it would’ve been neat. Especially since it’s a portentous turning point in Parker’s filmography.

Parker on edge in THE MAN WITH THE GOLDEN ARM.

Parker on edge in THE MAN WITH THE GOLDEN ARM.

Her next 1955 film came out in December; it hadn’t even begun shooting when Interrupted Melody released. The Man With the Golden Arm was Parker’s first film for United Artists (they borrowed her from MGM) and a return to black and white. It was a departure from Parker’s recent MGM work–Golden Arm is a gritty, grim tale of heroin addiction. Frank Sinatra is the lead, Parker’s his wheelchair-bound wife (so two of Parker’s three 1955 films had wheelchair aspects), Kim Novak’s Sinatra’s ex who reappears in his life. They all live in a not great part of Chicago, filled with crooks and pushers. Sinatra’s just gotten clean inside the joint (actually a rehab clinic) and wants to stay clean outside. He wants to be a drummer (hence the Golden Arm). Parker doesn’t make it easy for him, neither do the bad elements about. Otto Preminger directs the film, which is based on Nelson Algren’s acclaimed (and controversial) 1949 novel.

The Man with the Golden Arm (1955). ★★★. 2009 review

The Man with the Golden Arm (1955). ★★★. 2009 review

The Man with the Golden Arm has a lot of great performances, a lot of great filmmaking–a phenomenal Elmer Bernstein score–but it’s got its fair share of problems too. Walter Newman and Lewis Meltzer’s script is way too contrived, especially with the characters. Parker and Novak do well but their characters’ histories and ground situations are dubious concoctions. It’s also way too long, with the script picking choice moments for dramatic effect. It leads to disjointed character development–even though the actors smooth it all out. Parker’s awesome in her first villain role in almost a decade. Sinatra’s magnificent. He acts the hell out of Golden Arm. Excellent supporting turns from Darren McGavin and Arnold Stang. McGavin’s a pusher, Stang’s a mostly incompetent crook. And Preminger’s direction is excellent. He lets the film drag, but it’s an exquisite drag.

MAN WITH THE GOLDEN ARM: Novak invades Parker’s space.

MAN WITH THE GOLDEN ARM: Novak invades Parker’s space.

While critics embraced Golden Arm and its grit, the MPAA refused to give the film a Production Code seal due to the film’s controversial content. United Artists went back and forth, eventually giving up and (temporarily) dropping out of the MPAA. The Production Code was seen as necessary for box office success, but it didn’t end up stopping Man with the Golden Arm from selling tickets. Its domestic run was more than Interrupted Melody’s worldwide gross. It also got three Oscar nominations–Best Actor, Best Art Direction, Best Music. It didn’t win any. Somehow the film ended up in the public domain, which led to it being readily accessible over the years, though rarely with good quality releases. Magnetic Video first released the film on VHS in 1980, making it one of Parker’s first films to be released to home video. Fox put it out a couple years later on CED. Warner Home Video would put it on VHS in 1995, a LaserDisc following four years later. At that point, with DVD’s arrival, the public domain DVD companies started putting out editions. At one point, there were at least ten different releases of The Man With the Golden Arm on DVD, all bad quality. Until a Warner DVD release in 2008 struck from the original negative, the best release was sourced from a UK restoration (but not a restoration from the negative, rather a print). Golden Arm has always been accessible, though its trip through the public domain did some definite damage to its reputation.

Sixty plus years later, it’s still shocking Parker didn’t get a Best Supporting Actress nomination for Golden Arm.

KING AND FOUR QUEENS: Parker in Raoul Walsh Western. Finally.

KING AND FOUR QUEENS: Parker in Raoul Walsh Western. Finally.

After the three film year of 1955, Parker was absent from theaters for most of 1956. Her next film came in December, just over a year after Golden Arm’s release. The King and Four Queens was another United Artists picture, but color and not controversial. It’s a Western comedy. Parker’s second-billed after Clark Gable, whose production company–Gabco–co-produced the film. Gable’s the titular King, a Western adventurer who happens upon four young widows (and their mother-in-law). There’s hidden gold around and Gable aims to get it, seducing his way through the fetching Four Queens if he must. Parker’s the with-it widow (with secrets of her own). Jo Van Fleet is the no-nonsense mother-in-law. Raoul Walsh directs; he had directed They Died with Their Boots On fifteen years earlier, which would have been Parker’s first film… if she hadn’t ended up on the cutting room floor.

The King and Four Queens (1956). ★★½. 2006 review

The King and Four Queens (1956). ★★½. 2006 review

King and Four Queens is an entertaining little Western. It’s short–under ninety minutes (presumably because so much of it ended up on the cutting room floor; Walsh and Parker’s collaborations are cursed)–but Gable’s charming and one heck of a movie star. Parker and Van Fleet are both good. Richard Alan Simmons and Margaret Fitts write some good scenes for the actors. Walsh’s direction is quite good as well. King and Four Queens is slight–there’s obviously movie missing–but solid.

KING AND FOUR QUEENS: Royals Gable and Parker.

KING AND FOUR QUEENS: Royals Gable and Parker.

On release, The King and Four Queens was not particularly well-received by audiences or critics. Time dismissed it. Bosley Crowther savaged it in the New York Times, focusing on Gable’s fallen star stature. And while it was far from a box office bomb, it certainly wasn’t a big hit. It was also the last time Gabco Productions made a movie. Not good considering Four Queens was also the first Gabco production. As a producer, turns out Gable was a little petty–those massive cuts to Four Queens? Gable slashed Van Fleet’s role (and best scenes) because critics who’d seen the rushes thought she’d get an Oscar nomination for sure. It’s a shame, especially if Parker and Van Fleet had more scenes together. No story spoilers but… big time shame.

MGM/UA put King and Four Queens out on VHS in 1991; they pan-and-scanned the CinemaScope but Turner Classic Movies would soon be airing a letterboxed print. The film didn’t make it to DVD until 2009, from MGM (via Fox). That release went out of print at some point before 2014, when MGM put out a made-on-demand release. Olive Films has put out a Blu-ray release. Sadly no one’s ever included those deleted scenes.

Parker unleashes LIZZIE.

Parker unleashes LIZZIE.

Parker’s next film would again have a movie star producer–Lizzie is a Bryna production (Bryna being producer Kirk Douglas’s mom). MGM released the black and white film in April 1957. It’s a multiple personality drama; Parker’s the patient, Richard Boone is her doctor, Joan Blondell (who left Warner just a few years before Parker signed with them back in 1941) is the caring aunt, director Hugo Haas is the concerned neighbor. The film’s also got Johnny Mathis in his only film appearance. He has no lines, but a couple songs.

Lizzie (1957). ★★. 2016 review

Lizzie (1957). ★★. 2016 review

Clocking in at eighty minutes, Lizzie is way too slight. Director Haas botches the picture. Mel Dinelli’s script–adapted from a Shirley Jackson novel–is a disaster of its own, but Haas fails the film and Parker. Parker’s not even the film’s protagonist, she’s its subject. And no matter how strong her performance, she can’t carry it. Lizzie’s low budget, which wouldn’t be a problem if Haas–as a director–had any successful inventive ideas. He doesn’t. And his inventive ideas–hallucination sequences–are disastrous. The supporting performances are all perfectly solid, even with razor thin parts; the acting isn’t the problem, it’s Dinelli, it’s Haas.

LIZZIE: Not very happy days for Marion Ross and Parker.

LIZZIE: Not very happy days for Marion Ross and Parker.

Back in 1957, Lizzie was in a race with a Fox production, The Three Faces of Eve, to be the first multiple personality drama of the year. Lizzie won the race (Eve came out in the fall). Contemporary critics were far from impressed with Lizzie. Bosley Crowther tore into it in The New York Times. Audiences stayed away too. The film barely made its low budget back (and didn’t make enough to turn any profit). MGM had been hoping for an Oscar nomination for Parker–which must have been particularly disappointing considering Joanne Woodward didn’t just get nominated for Eve but won. The studio blamed Haas for not directing Parker better. They weren’t wrong.

Until Warner Archive released a DVD in 2016, the only way to see Lizzie was on Turner Classic Movies, where it irregularly aired (most often for Parker birthday marathons). It’s good for the film to have that release, sure, but it’s such a disappointment. Parker, whose versatility is her biggest trait, in a multiple personality role… well. It’s rather unfortunate how much Haas, Bryna, and MGM screwed it up. Worse, Lizzie’s failure would be the start of Parker’s career decline (at least in terms of production and role quality)–just two years after it found the peaks of Melody and Golden Arm.

THE SEVENTH SIN: Parker and Travers. Travers is the one having trouble convincingly pointing.

THE SEVENTH SIN: Parker and Travers. Travers is the one having trouble convincingly pointing.

Parker’s next film of 1957, The Seventh Sin, came out about three months after Lizzie. Again at MGM, again in black and white–though this time CinemaScope black and white–Seventh Sin is a W. Somerset Maugham adaptation. Parker is an adulteress in post-war Hong Kong. Her lover, Jean-Pierre Aumont, is a charming French industrialist. Her husband, Bill Travers, is an obnoxious British medical doctor. When Travers realizes Parker’s stepping out, he forces her to accompany him to a cholera epidemic in rural mainland China. There they meet friendly ex-pat George Sanders and Parker tries to survive without the trappings of cosmopolitan life. Ronald Neame directs; Sin is his first American project after ten years making pictures in the UK. At least it was his project until MGM fired him and brought in Vincente Minnelli to finish the picture. Minnelli didn’t take any credit. Karl Tunberg, who co-wrote Valley of the Kings, handles adapting the Maugham novel here.

The Seventh Sin (1957). ★★★. 2017 review

The Seventh Sin (1957). ★★★. 2017 review

Unlike Valley of the Kings, Tunberg writes one heck of a role for Parker in Sin. She’s got a phenomenal character arc and Parker burns through it. She gets fantastic support from Sanders as her pal and–shockingly given it’s Sanders–moral compass. Unfortunately, Bill Travers’s performance is jaw-droppingly bad. Even with the behind the scenes drama (Neame didn’t like Parker’s performance so his firing makes all the sense), Sin is rather well-directed. The story has an epic scale–and while the film had a not insignificant budget of $1.5 million, it’s not an epic budget. Parker, Sanders, Aumont, and Françoise Rosay are all good. Sin’s all about Parker’s magnificent performance (and cringing through Travers’s). The rushed third act–Sin runs a little short at ninety minutes–and the “Chinese” Miklós Rózsa score are other problems. But nothing compared to Travers’s acting.

Aumont and Parker sin in THE SEVENTH SIN.

Aumont and Parker sin in THE SEVENTH SIN.

Critics–at least Bosley Crowther in The New York Times–welcomed Seventh Sin indifferently; though he did like Parker’s performance. Audiences were even more indifferent. Seventh Sin didn’t even make back half its budget; not a successful end to Parker’s five-year MGM contract. Sin didn’t have a home video release until the Warner Archive DVD in 2016, which presented it widescreen. The rare Turner Classic Movies showings had been, at least until that time, pan and scan. Parker’s work in the film deserved (and deserves) a lot more recognition. Plus, it’s her only pairing with the indomitable Sanders; they’re a delight to watch together.

Following the disappointments of 1957–both pictures with so much potential for Parker, she didn’t have any releases in 1958. She was busy parenting a newborn again; son Paul Day Clemens was born in January of that year.

A HOLE IN THE HEAD: All smiles for Sinatra, Hodges, and Parker.

A HOLE IN THE HEAD: All smiles for Sinatra, Hodges, and Parker.

Her next film, A Hole in the Head, came out summer 1959. The film reunites her with Golden Arm co-star Frank Sinatra, though Hole is far from that picture’s grim and gritty (and black and white) Chicago. Instead, the action takes place in the bright Deluxe color pastels of Miami Beach. Sinatra’s a ne’er-do-well single parent hotel manager. Eddie Hodges is the adorable son. Edward G. Robinson is Sinatra’s successful, but boring, older brother (who Sinatra’s hitting up for money). Thelma Ritter is Robinson’s wife, Carolyn Jones is one of Sinatra’s tenants–a twenty-one year-old “free spirited” egoist he’s romantically involved with. Parker eventually shows up as a proper romantic interest for Sinatra, at least according to Robinson and Ritter. Frank Capra directs the film–his penultimate feature; he and Sinatra produced the film together (making it Parker’s third project for actor-producers in the fifties).

A Hole in the Head (1959). ★★½. 2015 review

A Hole in the Head (1959). ★★½. 2015 review

A Hole in the Head runs a couple hours and doesn’t start getting good until the second hour. It doesn’t start getting better than good until the final act, which is too bad. Arnold Schulman adapted his play for the screen, but that adaptation has some weird choices. The film needs a tight script, not a weird one. These actors deserve far better material. Capra’s lackadaisical direction of the cast doesn’t help things. But once it gets going–i.e. Sinatra getting a character to play instead of just being a heel–the film improves immediately. Though Capra’s boring CinemaScope composition never improves. Parker’s good in a glorified cameo (a couple of her scenes were, of course, cut). She and Sinatra get at least one good scene and Parker does a lot with the part. The actors save A Hole in the Head.

HOLE IN THE HEAD: Sinatra tries hard on his grown-up date with Parker.

HOLE IN THE HEAD: Sinatra tries hard on his grown-up date with Parker.

The film was a big hit on release–the eleventh highest grossing film of the year. Critics liked it too; A Hole in the Head made Time’s top ten list. It also won an Oscar for its original song, High Hopes. MGM put the film out on VHS and LaserDisc (in the film’s OAR) in 1993. They also got it out on DVD in 2001, though that release has since gone out of print. Olive Films has picked it up and released both a DVD and a Blu-ray. And the film’s available streaming. During the thirty-five years between theatrical release and home video, however, the film’s reputation is unclear. One assumes, because of the always popular Sinatra headlining, it at least enjoyed regular television play (before Turner Classic Movies would’ve taken those airings over).

As a Parker film, A Hole in the Head foreshadows her sixties career far more than it culminates her fifties’. She’s third-billed in A Hole in the Head and her part’s somewhat consequential (in what remains of it anyway), it’s just not a big part. It’s a small part, definitely smaller than the cast billed after her.

Parker frets (with cause) over Hamilton.

Parker frets (with cause) over Hamilton.

In early 1960, Parker’s last theatrical picture for MGM came out. Once again in CinemaScope, but now in Metrocolor, Home from the Hill is epic melodrama. Robert Mitchum is a millionaire Texan, Parker’s his wife, George Hamilton’s their foppish teenage son, George Peppard’s Mitchum’s bastard. Parker has been shutting Mitchum out since she arrived in Texas with newborn Hamilton and discovered toddler Peppard. The film starts up with Mitchum surviving yet another attack from an angry cuckold–Mitchum’s needs come before fidelity–but soon becomes the story of Hamilton and Peppard’s friendship as Hamilton tries to butch it up as a young Texan. Vincente Minnelli directs the film (credited this time), with Harriet Frank Jr. and Irving Ravetch scripting from William Humphrey’s (sometimes much different) novel.

Home from the Hill (1960). ★★★★. 2006 review

Home from the Hill (1960). ★★★★. 2006 review

Home from the Hill is a CinemaScope spectacular. Minnelli’s direction is outstanding, both in terms of composition and of his actors. Frank and Ravetch’s script is patient and deliberate–the film runs two and a half hours so they have time to be both. Of the four principals, Parker gets the least screen time but still has a full character arc or two. She and Mitchum’s angry, resentful relationship turns out to be the film’s backbone, with the adventures of the two Georges taking up the foreground. Great performance from Mitchum too. Parker turns what should be a histrionic part into anything but. While in full Southern accent. The two Georges’ performances impress as well; beautiful photography from Milton R. Krasner. Home from the Hill is awesome.

Parker and Mitchum are trapped in HOME FROM THE HILL.

Parker and Mitchum are trapped in HOME FROM THE HILL.

And it was a hit on release. Not enough of a hit to turn a profit, but at least one of the top twenty grossing pictures of the year hit. Critical response was similarly strong–though not uniformly–and the film was selected for Cannes. Mitchum got Best Actor from the National Board of Review, George Peppard best supporting. The National Board of Review also put the film on their annual top ten list. MGM released Home from the Hill on VHS and LaserDisc in 1990, the LaserDisc a “deluxe letter-box edition” preserving Minnelli and Krasner’s wondrous CinemaScope. Warner released a DVD in the 2007 and the film’s now available streaming. Again, in the thirty years between theatrical and home video, Home from the Hill most have gotten television play… it just didn’t build a sustained reputation. Unfortunately.

While Home from the Hill certainly showcased Parker’s versatility and development as an actor–though she’s a little young to be Hamilton’s mom, the film pulls it off through the magic of Hollywood melodrama–and it’s an MGM release, it doesn’t prove an appropriate capstone to her fifties work. Even though it’s great and she’s great in it, the potential of Parker’s fifties work was never realized. Both Lizzie and Seventh Sin could have given her great roles, but didn’t. Parker was always a nimble actor–her toggle from the filmed stage-play of Detective Story to the grand cinema of Scaramouche set her career on the MGM trajectory and the studio got her some great roles and some excellent films resulted. Even when the films stumbled, Parker could still excel.

Of the sixteen films Parker made after leaving Warner Bros., nine of them feature singular performances. Excepting Valentino and Valley of the Kings, the remaining five performances are all excellent.

Eleanor Parker could do anything and everything, but Hollywood (and moviegoers) tend to want their stars to do just one thing, leaving her boundless range at least underappreciated when not being completely unappreciated. But the bulk of her fifties work is available streaming. It’s her decade, from Caged to Hill, with all these magnificent performances in between.

For her fifties output, Parker’s performance makes the movies. And the filmmakers tend to understand it–Detective Story, Above and Beyond, Naked Jungle, Interrupted Melody. Studios wanted their stars to make the movie, not their stars’ performances. Parker’s fifties work shows the two don’t have to be mutually exclusive. Brilliantly so.

RELATED

- Eleanor Parker, Part 1: Dream Factory

- More

![20171231_110343_001[1]](/ai/021/110/21110.jpg)