It’s 2018, a new year has begun with the possibility for all manner of interesting events to come! But what were people thinking about two thousand years ago? In 18 AD the Roman Empire was busy fighting wars in Germany, Africa and Syria with the imperial general Germanicus having won fame and public admiration for his victories and triumph the year before. A new year was soon to begin with many developments to come.

Tiberius – Reigning emperor in AD 18. Germanicus – Popular general.

State of the Roman Empire during the reign of Tiberius.

AD 18 began on a Saturday, but the Romans knew it as the ‘Year of the consulship of Augustus and Caesar’. They used to call their years by the sitting consuls that year; during this year, they were occupied by Emperor Tiberius and his nephew/adopted son Germanicus Caesar. Germanicus had risen to prominence for his victories against the Germanic tribes which had waged a ferocious war against Rome. Nine years ago, they had risen in revolt and slaughtered the three legions sent to subdue them at Teutoburg Forest; leaving barely any survivors. The Romans had even lost their three legionary eagle standards which caused great shame among the people. Archaeologists have never discovered a Roman eagle…ever. It was such a humiliation to have one fall into enemy hands that before a defeat the standard would be utterly destroyed by the soldiers themselves.

French Imperial Eagle – No Roman eagle has ever been discovered.

Roman mass grave in Germania – Thousands of remains were buried by Germanicus.

Military campaigning would temporarily cease for several years until after the death of Emperor Augustus. During the inter regnum the Rhine Legions had risen in revolt against the new emperor Tiberius (something about not being paid). Germanicus, the commanding officer then casually suggested that the legionaries seize their rightful bonuses…from the Germanic tribes across the river. Several dead Germans and three recaptured eagles later, Germanicus returned to Rome to celebrate a triumph in 17 AD. This presumably left more than a couple of Romans hungover the following morning.

Roman triumph as depicted by HBO’s ‘Rome’ – A celebration and festival.

Due to his immense popularity he was voted as one of the Consuls the following year. Thus 18 AD, began with general jubilation and comfort as the German defeats appeared to have been avenged by the emperor’s nephew/adopted son. If the relationship between Tiberius and Germanicus is weirding you out, it’s a thing the Romans used to do to personally adopt their political allies. Caesar actually adopted Octavian (Augustus) who had been his nephew. He was now Tiberius’ nephew, adopted son, general and political rival; as you can see Roman dynastic politics was intense.

With Germanicus’ popularity among the people and the troops, rumours were sure to spread amongst the imperial court. It was not that long ago that Tiberius legions had rebelled and attempted to place Germanicus on the throne. Despite his apparent unwavering loyalty, the emperor was surely cautious in how he might treat a potential rival. More victories would weaken his position as the legitimate emperor, while hostility/ assassinating him would bring the hatred of the Roman mob upon him. And as everyone knew from the fall of the Republic, the fury of the mob could topple anything. The Senate had conferred the throne onto Tiberius, but real authority lay with the legions; their loyalty was first to their commanders, and then the emperor himself (unless he bribed them). The celebrations of the resolution of the German fiasco had temporarily brought stability to the province, but the political affairs in Rome were still uncertain.

Rome’s Legions were the source of imperial political power.

As it happens, in that year Germanicus was sent to Syria to re-establish order in the province which was arguable the wealthiest in the empire. Unfortunately for him, Tiberius had changed the governor of Syria from Creticus Silanus, an ally of Germanicus, to Cneius Piso; who was according to Tacitus meant to act as a foil to anything his nephew might try to achieve.

‘Tiberius had however removed from Syria Creticus Silanus, who was connected by a close tie with Germanicus, his daughter being betrothed to Nero, the eldest of Germanicus’s children. He appointed to it Cneius Piso, a man of violent temper, without an idea of obedience…. He thought it a certainty that he had been chosen to govern Syria in order to thwart the aspirations of Germanicus.’ Tacitus, Annals 2.43.

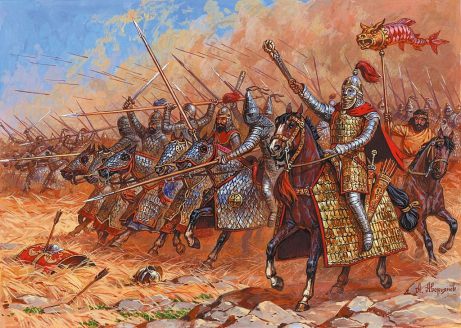

This isn’t so hard to believe since any setbacks in the province could be blamed on Germanicus, and if he were to suddenly die then Piso could make a convenient scape goat. Syria was also a contested region with the Parthian Empire which was also hostile to Rome. Forget the Germans, the Parthians had captured 7 eagle standards at Carrhae not that long ago. It was only through diplomacy that Augustus retrieved them. During this year, the most pressing concern was the status of Armenia which had been playing both Rome and Parthia in order to survive. The assignment to the East was a dangerous proposition and one with a considerable risk of failure.

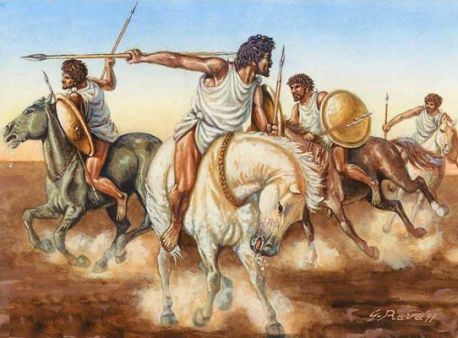

Parthian heavy cavalry and horse archers had annihilated the Romans in 53 and 33 BCE.

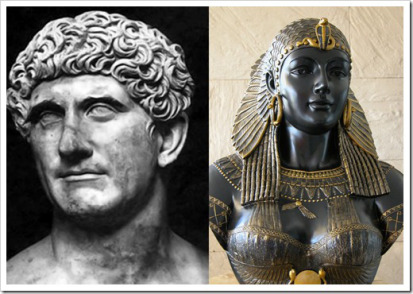

Control of the wealthy Eastern half of the empire was also what had doomed the Germanicus’ grandfather: the infamous general Mark Antony, during the civil war. By moving away from the center of power at Rome, he allowed Octavian to smear him to the Senate and Roman people as a bibulous traitorous boyfriend to Cleopatra. He had also attempted to invade Parthia and been humiliatingly defeated. These misfortunes led to his eventual downfall and Octavian’s rise as emperor. Factionalism and civil war was still present in many Romans’ minds in addition to their hatred against the Parthians.

Mark Antony’s Eastern command caused rumors of treachery and decadence with Cleopatra.

What’s more, during the previous year twelve cities were destroyed by an earthquake: a terrible omen as well as an opportunity for Tiberius to increase his approval ratings at the literal expense of his political rivals. The omens did not improve as Germanicus traveled to Syria:

‘he coasted back along Asia, and touched at Colophon, to consult the oracle of the Clarian Apollo. There, it is not a woman, as at Delphi, but a priest chosen from certain families, generally from Miletus, who ascertains simply the number and the names of the applicants. Then descending into a cave and drinking a draught from a secret spring, the man, who is commonly ignorant of letters and of poetry, utters a response in verse answering to the thoughts conceived in the mind of any inquirer. It was said that he prophesied to Germanicus, in dark hints, as oracles usually do, an early doom.’ Tacitus, Annals 2.54.

These omens and foreshadowing seem so unlucky, it’s like he’s going to die and never return to Rome; spoilers. Anyway, the trope of the omens before the death of a great man is present in all accounts of the deaths of leaders from Alexander the Great to Julius Caesar. When Germanicus was sent to the East, there probably was some possibility (or hope) that he was never coming back alive. During the year he would manage to sign a peace treaty with Artabanus III of Parthia and place the pro-Roman king Artaxias III onto the Armenian throne, despite Piso’s best efforts to undermine him.

‘Successful as was this settlement of all the interests of our allies, it gave Germanicus little joy because of the arrogance of Piso. Though he had been ordered to march part of the legions into Armenia under his own or his son’s command, he had neglected to do either. At length the two met at Cyrrhus, the winter-quarters of the tenth legion, each controlling his looks, Piso concealing his fears, Germanicus shunning the semblance of menace.’ Tacitus, Annals 2.57.

The peace in the East had stabilized Roman borders at the expense of Piso’s pride as the negotiations had excluded him as governor of Syria. But this was only one border of the vast empire which Tiberius controlled. The German traitor Arminius who had massacred the legions at Teutoburg forest was still at large and had even defeated a rival tribe called the Marcomanni, further consolidating his position as leader of the Germans after his defeats inflicted by Germanicus. While in Africa, another deserter, this time the Numidian Berber Tacfarinas had begun a revolt. The local Roman forces were struggling to fight against the hit and run tactics of the Berbers who harassed their villages, supply lines and patrols. Although a decisive pitched battle was fought, Tacfarinas had escaped into the desert and still remained at large. Rome’s troubles on the frontier were far from over.

Numidian berbers were known for their swift light cavalry.

At the beginning of and during 18 AD, the empire’s borders while quiet, were far from totally secure. The year also marked by political machinations in response to Germanicus’ victories in Germania and Tiberius’ own need to maintain political control over the legions and provinces of the empire. The year held substantial opportunity and risk for the members and key players in the imperial court. Memories of revolt and civil war were still fresh as Rome’s expansion had halted and a period of stagnation and decline must have been speculated. The year would unfold without much explosive incident; but 19 AD would not go down the same way.

Dan Tang

The Athenian Inspector

Thanks for reading!! If you want to learn more about the Romans, check out: https://romanimperium.wordpress.com/

Advertisements Share this:

![20171231_110343_001[1]](/ai/021/110/21110.jpg)