I was unable to attend the first two events in this the 2017 season of West Sussex History of Medicine Society, so forgive me for the absence of write ups. However, I am pleased to say that I made it to the Remembrance Day event, and was very impressed with the lectures. Impressive too was the very full house who came out on a rainy Saturday morning on this the 99th anniversary of Armistice Day. Before I give my précis I would like to say how moved I was to join my personal silent Remembrance heart with everyone else’s, especially as so many army men were there, who must feel the sadness of so much loss far more deeply than I.

I was unable to attend the first two events in this the 2017 season of West Sussex History of Medicine Society, so forgive me for the absence of write ups. However, I am pleased to say that I made it to the Remembrance Day event, and was very impressed with the lectures. Impressive too was the very full house who came out on a rainy Saturday morning on this the 99th anniversary of Armistice Day. Before I give my précis I would like to say how moved I was to join my personal silent Remembrance heart with everyone else’s, especially as so many army men were there, who must feel the sadness of so much loss far more deeply than I.

There were, as usual, two presentations, and I will publish my précis of the second one at a later date,

‘The Life And Legacy of Professor Dr Nikolai Pirogov’

Major General Mungo Melvin CB OBE MA

– by Major General Mungo Melvin CB OBE MA, of the Royal Engineers.

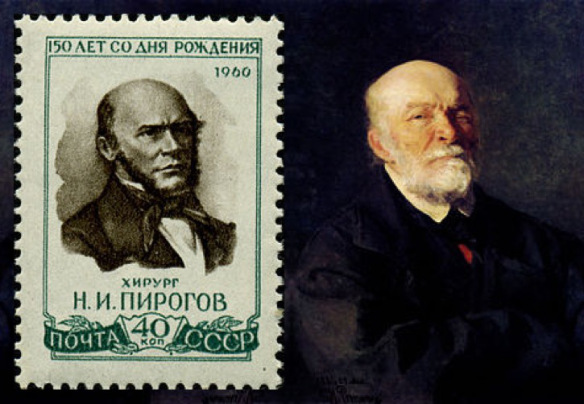

Before this lecture I had not heard of Dr Nikolai Pirogov, but the first thing that struck me about was his likeness to Charles Darwin. The photo below is of a commemorative USSR postage stamp from 1960. Next to it is Pirogov as an old man, and here the resemblance with Darwin is no longer present.

So, who was he and what did he do? Dr Pirogov (1810 – 1871) was a noted surgeon, but, in one respect, he was also similar to England’s Florence Nightingale in that he, like she, brought about major changes in medical and nursing care which significantly increased the survival of injured or sick soldiers and changed the approach to nursing the world over. Both were engaged in the same theatre of war, in the Crimea, and both applied their considerable talents to making lasting changes to the handling of such situations. The scale of this war produced thousands of injured and ill with all sorts of ailments, such that it overwhelmed the previous means of managing injured soldiers, and this was because this was the first modern war, waged with industrial power like never before.

The advances in military technology vastly increased not only the number of soldiers involved, the extent of the field of conflict and the power to destroy, but also the duration of attacks due to reinforcements being brought in constantly. Huge steam ships deployed by the British and French furnished their large armies with massive quantities of ammunition, so bombardments could be far more sustained, and far more devastating than had hitherto been seen.

At the outbreak of the Crimean War in 1853 Pirogov was working as a surgeon, (unlike Nightingale, of course, who was a dainty, educated, protected, young Victorian maiden). As a surgeon Pirogov had recently adopted the newly discovered method of using ether for anaesthesia which, since 1847, had revolutionised the scope of the surgeon. At the Crimean war zone, however, he was utterly appalled by the lack of care for wounded men, who were suffering and dying for want of timely nursing attention, bandages, sanitation, adequate food, beds, clothing and shelter, quite apart from their need of urgent surgery.

His letters criticising the General Menshicov, the Comander in Chief at Crimea, for his poor management of the situation, meant he was not promoted nor properly acknowledged by his superiors, but as a thorn in their sides his writing and complaints about conditions for the men spurred on a new and powerful movement which saw noble women, including the Grand Duchess Yelena Pavlova, coming in droves to bring their nursing and organisational skills to bear in the service of the wounded and sick, just as Florence Nightingale did with ladies from England. So the names of Pirogov and Nightingale are somewhat intertwined for their humanity and good sense, though they served on opposite sides of that war.

Pirogov is considered The Father of Field Surgery as he managed to deal with extraordinary numbers of casualties that would pour in over a very short period of time. One 24 hour episode saw him dealing with over 400 injuries during an intense bombardment at the Siege of Sevastopol. In this time he performed 30 amputations. Indeed the Pirogov Amputation is named after a particular method he described and taught. This level of demand on a surgeon had, hitherto, never been seen and he was considered a war hero by the end of the war in 1856.

In retirement he became a general practitioner and on his death his body was embalmed and is still available to view, in a glass display casket! Interestingly, it is still in perfect condition, (unlike that of Vladimir Lenin which apparently needs to be kept ‘topped up’ with goodness knows what chemicals, to prevent it from disintegrating). The embalming recipe used in Pirogov’s case has been kept secret. Here he is:

- You can read more from our speaker Major General Mungo Melvin, especially his work for his new book Sevastopol’s Wars at his website mungomelvin.com

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSaveSaveSave

SaveSaveSaveSave