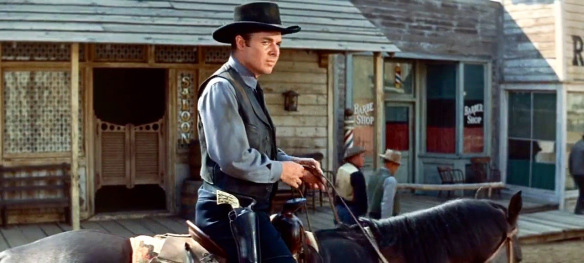

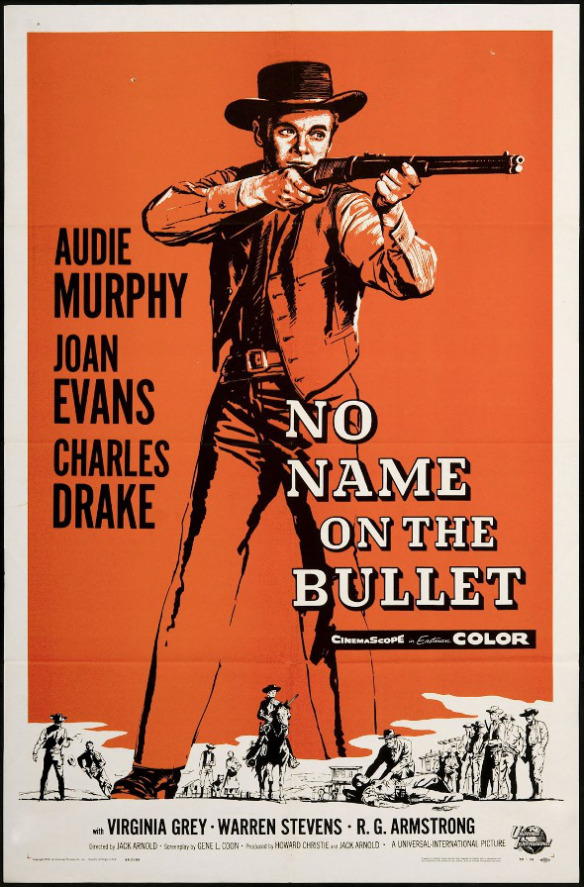

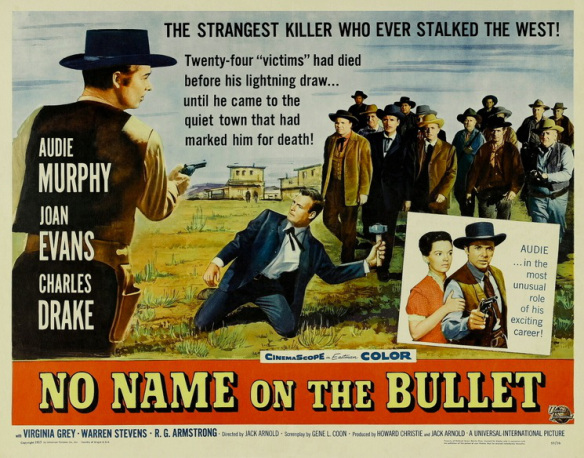

Audie Murphy plays an angel of death in the semi-allegorical western western, No Name on the Bullet (1959), directed by Jack Arnold

Clint Eastwood certainly carved out his own genre niche as “The Man With No Name” gunslinger of Sergio Leone’s spaghetti western trilogy but he wasn’t the first to craft his screen persona as an archetype of the tight-lipped, deadly frontier drifter. Audie Murphy had already perfected the prototype in No Name on the Bullet (1959), a much darker variation on the heroic lawmen the actor usually played in westerns.

Audie Murphy, World War II hero

Of course, real life heroes rarely get to play themselves on screen, but Audie Murphy was a unique exception even though in hindsight his Hollywood career seems to be a complete anomaly. On screen his baby face and boyish demeanor is completely at odds with his reputation as World War II’s most decorated war hero – the recipient of twenty-four decorations, one of which was the Congressional Medal of Honor. How many movie stars can claim that distinction?

Audie Murphy stars in The Red Badge of Courage (1951), directed by John Huston.

His acting abilities, however, were minimal but some directors knew how to exploit Murphy’s limited range to good advantage such as John Huston in The Red Badge of Courage (1951) and The Unforgiven (1960). And Murphy himself knew he was best in roles which were closer to who he really was: a highly skilled soldier who was trained to kill. That’s why his performance as himself in the autobiographical To Hell and Back (1955) is one of his best. Murphy was also ideally cast in Westerns, a genre he specialized in for most of his career, with The Kid from Texas (playing Billy the Kid) and Kansas Raiders (as Jesse James) being the two high points of his early film career at Universal (both were released in 1950).  It was in the later Westerns Murphy made for that studio that he really came into his own, playing quietly intense loners who were fast with a gun. No Name on the Bullet (1959), in which Murphy plays a hired gunman who rides into the sleepy town of Lordsburg with a mission, could have been a model for Eastwood’s “Man With No Name” anti-hero of A Fistful of Dollars and two sequels.

It was in the later Westerns Murphy made for that studio that he really came into his own, playing quietly intense loners who were fast with a gun. No Name on the Bullet (1959), in which Murphy plays a hired gunman who rides into the sleepy town of Lordsburg with a mission, could have been a model for Eastwood’s “Man With No Name” anti-hero of A Fistful of Dollars and two sequels.  Impassive yet deadly, Murphy’s hired assassin disrupts the town with his presence, creating an atmosphere of paranoia as various townspeople with secrets to hide become convinced the gunman was come to kill them. Murphy’s target is eventually revealed; he is the town judge (Edgar Stehli), now dying of consumption and confined to a wheelchair. Their fatal confrontation is played out in a surprising and unconventional denouement.

Impassive yet deadly, Murphy’s hired assassin disrupts the town with his presence, creating an atmosphere of paranoia as various townspeople with secrets to hide become convinced the gunman was come to kill them. Murphy’s target is eventually revealed; he is the town judge (Edgar Stehli), now dying of consumption and confined to a wheelchair. Their fatal confrontation is played out in a surprising and unconventional denouement.  Unlike most of Murphy’s earlier Westerns, No Name on the Bullet has a philosophical edge which makes it closer in tone to Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957) than a six-gun oater like Destry (1954), a distinction noted by author Don Graham (in his biography of Murphy entitled No Name on the Bullet).

Unlike most of Murphy’s earlier Westerns, No Name on the Bullet has a philosophical edge which makes it closer in tone to Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957) than a six-gun oater like Destry (1954), a distinction noted by author Don Graham (in his biography of Murphy entitled No Name on the Bullet).

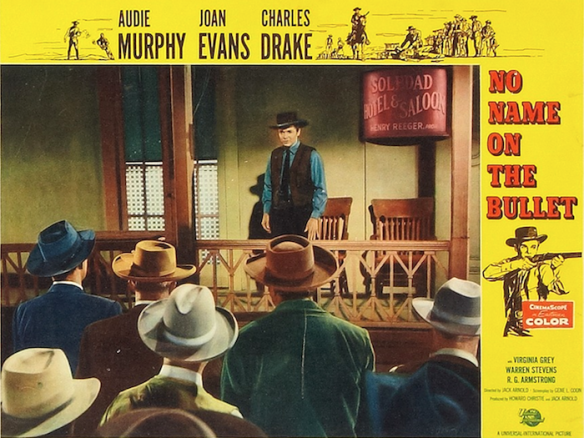

Audie Murphy plays a remorseless assassin in No Name on the Bullet (1959), directed by Jack Arnold.

For one thing, Murphy’s angel of death is balanced against Luke (Charles Drake), the town’s physician who is committed to saving lives. Similar to the chess game played between Death and the knight Antonius in The Seventh Seal, No Name on the Bullet occasionally pauses to compare the contrasting viewpoints of these two men. Murphy has no use for the townspeople, stating, “They’re going to die anyway. Best you can do is drag out their worthless lives. Why bother?” But Luke counters with “I’m a healer. I’ve devoted my life to it and I intend to continue. Right now I’ve got one big public health problem, and I’m looking at it.”

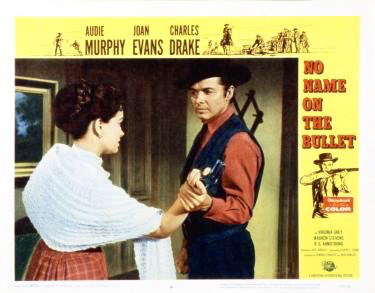

Audie Murphy (left) and Charles Drake play frontier men with opposing philosophies in No Name on the Bullet (1959).

Like Eastwood’s flinty drifter in A Fistful of Dollars (1964), Murphy is equally deadpan and expressionless throughout most of No Name on the Bullet except for his eyes. And this was true of Murphy off the set as well. According to frequent co-star Morgan Woodward (Ride a Crooked Trail (1958), Gunpoint, 1966) in Graham’s aforementioned biography, Murphy’s “eyes almost seemed to dance. They had a deadly gleam, a deadly wild look. I would not have wanted to cross him.” This suggestion of inner violence ready to erupt is what makes Murphy’s performance in No Name on the Bullet one of his best.

Audie Murphy on the set of Jack Arnold’s No Name on the Bullet (1959).

Murphy, however, wasted little time on analyzing his acting or reading critical notices; he saw movies as little more than profitable work for hire. But he was well served on No Name on the Bullet with Jack Arnold in the director’s chair and Gene Coon providing the screenplay. Arnold, best known for sci-fi/horror genre efforts such as It Came from Outer Space (1953) and Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), has enjoyed a critical resurgence in recent years with film scholars re-evaluating his work.

Film Director Jack Arnold

On the surface, much of Arnold’s work was typical B-movie product for the studio but on closer inspection entries like The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957) and No Name on the Bullet prove to be more thematically complex and thought-provoking than any ordinary B-picture. As for Gene Coon, most sci-fi geeks know him as one of the major scenarists on the Star Trek TV series; he introduced the Klingons to viewers in the first season episode “Errand of Mercy.”

NO NAME ON THE BULLET, Poster Art, Audie Murphy, Joan Evans, 1959

No Name on the Bullet was released as a solo DVD in 2004 as part of the Universal Western Collection. It was presented in the appropriate widescreen ratio and the Eastmancolor looked vibrant for a process that was notorious for losing its original luster within a brief timespan. But a Blu-Ray restoration upgrade from Universal would be more than welcome.  *This is a revised and updated version of an article that originally appeared on the Turner Classic Movies website.

*This is a revised and updated version of an article that originally appeared on the Turner Classic Movies website.  Other websites of interest:

Other websites of interest:

http://www.history.com/news/audie-murphys-world-war-ii-heroics-70-years-ago

http://www.check-six.com/Crash_Sites/Audie-Murphy-N601JJ.htm

https://truewestmagazine.com/1959s-no-name-on-the-bullet/

http://thefilmexperience.net/blog/2016/10/14/jack-arnold-centennial.html

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QrPWfqVuISM

Advertisements Share this: