I have gone into back to basics mode: what does it mean to tell a story? I have been reading a lot of short stories since giving up on A Game of Thrones for what must be the eightieth time. Not just fantasy or science fiction, but authors of all nationalities, genres, and styles. I have been reading Chekhov, Stephen King, Margaret Atwood, Flannery O’Connor, and others who I used to read before I got the idea that I had to give myself assignments and read stuff that was current. I’ve noticed a couple of interesting things:

- I read faster and without losing interest when I read these stories; on the other hand when I try to read current releases in the elite scifi markets, I get bored and have to struggle through. A 4,000 word story can take me days to read due to all the distractions I allow.

- A short story is not that different from how one tells a story as in “let me tell you a story.” I had completely forgotten this in all my struggle to learn about structure and other story fundamentals. It has encouraged me to “just write,” at least in first drafts. If you look over this blog you’ll see plenty of encouragement to outline, but I’m losing faith in the idea that strict outlining is a good idea in first drafts.

These two points are exquisitely illustrated by my recent readings of William Gibson‘s short stories in the collection Burning Chrome. Gibson’s stories seem crazy complex on the surface, which is a definite influence of William S. Burroughs. The Burning Chrome stories have a voice that is never afraid to mention details and an attitude that respects the reader, i.e. never expects the reader can’t pick up on what the narrator is saying. However, any such narrator is always forthcoming with details and enough context so the reader never doubts what’s going on. Even though I know that in many of these stories the author is completely bullshitting with his knowledge of science and technology, he does it extremely effectively. I see writers try to do this and pretty often and, even in published stories, it just totally doesn’t hold up. It sounds stupid. Not so with Gibson.

William Gibson, By Gonzo Bonzo – originally posted to Flickr as William Gibson, CC BY-SA 2.0, Link

William Gibson, By Gonzo Bonzo – originally posted to Flickr as William Gibson, CC BY-SA 2.0, Link

Particularly the story “New Rose Hotel” exemplifies all these qualities. I read this in the car on the way back from Canada on Wednesday and discovered that although it was a 4,000 word story, it completely held me: I didn’t know how long it took me to read and I didn’t care. I re-read it right away. It’s a dizzying story about a group of industrial espionage agents doing the job that means they won’t have to work anymore. The industry is futuristic genetic engineering, and the story goes back and forth, actually told in second person retrospective. You and the narrator together have to go back and figure out what happened. Although the details are hectic and the exact nature of the ending is slightly unclear in its technical details, we know what it means for the characters.

I mention that the story is in second person because this is a technique that a lot of writers are trying (and getting away with, if that means publication) and often it totally falls flat. The typical employment of second person these days is “You do this, you do that, and you feel this way” to which my reaction is “No, I don’t.” What worries me more is that this may have come into usage not from literary influences but from roleplaying and video games. Gibson’s use of second person in “New Rose Hotel,” on the other hand, is like this:

We thought we’d found you, Sandii, but really you’d found us. Now I know you were looking for us, or for someone like us. Fox was delighted, grinning over our find: such a pretty new tool, bright as any scalpel. Just the thing to help us sever a stubborn Edge, like Hiroshi’s, from the jealous parent-body of Maas Biolabs.

What I found on immediately reading through it was that the complex and hectic nature of the story was an illusion. Gibson very carefully introduces the situation and each of the three main characters (the narrator, Fox, and Sandii, to whom the story is directed). Even with the auxiliary characters he methodically lays out who they are in the world, why they are important, even what they look like. It’s brilliant how he does this without even letting the reader notice. He tells a story, plain and simple, but makes it look anything but plain and simple.

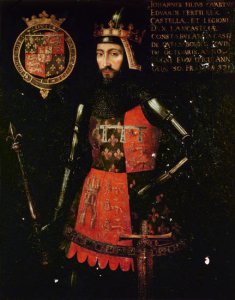

I have gone back to Shakespeare as well, and my favorite play Richard II. Richard’s story is intriguing historically and in Shakespeare’s characterization for a lot of reasons. Richard was a young king (just like Henry VI), his reign saw outbreaks of black death, rebellion by peasants, and finally his overthrow at the hands of Henry Bolingbroke. Although Richard II was my favorite play, it was mainly because of the beautiful speeches Richard and John of Gaunt (Lancaster) deliver, and not because I understood the plot. The plot has always seemed too simple to me: Richard banishes Bolingbroke, John of Gaunt dies, and Bolingbroke returns and overthrows Richard. I felt like I was missing something.

Richard’s Uncle, John of Gaunt

Richard’s Uncle, John of Gaunt

I realized that if a play lasts (on average) 2.5 hours, then I should be able to read a whole play in one sitting if I have such a chunk of time. I do if I stay up after the kids go to bed, so during our Christmas trip to Canada I read Richard II in about three hours with just a few breaks. The plot is much clearer this way, just as if you read a short story in one sitting. Not only is Shakespeare’s plot clear, but it’s spelled out quite clearly by the characters. I often catch myself thinking the motivations of the characters are subtle in Shakespeare, but when I bother to actually listen, they say exactly what they want, they say what they’re going to do and when they’re going to do it. Iago says “I hate this guy and I am going to destroy him” and then we spend another two hours watching him do it.

King Richard spends all of Act I buddying up to his former guardian, his uncle John of Gaunt. When they’re in the same room, Richard says how tragic it is that he had to banish Gaunt’s son, and dissuades Gaunt from his morbid feeling that he won’t see his son again. Then in the final scene of Act I, when Richard’s pals arrive and tell him Gaunt is sick, Richard says “Oh good, let’s go see him and hope that we’re late” because he plans on robbing him to finance his war in Ireland. Then he does it.

Now put it, God, in the physician’s mind

To help him to his grave immediately

The lining of his coffers shall make coats

To deck our soldiers for these Irish wars.

Come, gentlemen, let’s all go visit him;

Pray God we may make haste and come too late!

Richard’s fall is tragic because to the end, although he has occasional glimmers of his own humanity, he clings to the idea that he has the divine right to rob his subjects, including nobles. In his famous speech about the death of kings, he says his friends have mistook him: he eats bread and needs friends just like every other human being. When Bolingbroke challenges him, however, he clings to the idea that Bolingbroke won’t defy his divine right. And he’s wrong. The entire nation is against him and wants him off the throne. Incidentally, seeing people cling to ideas that were plainly wrong, denied by piles of data, and just ridiculously stupid was a big part of why I left science.

Shakespeare may have been telling a current lesson about the nature of authority during the reign of Elizabeth, but he also hit upon an important artistic lesson: to make someone fall, all you have to do is make them cling to an idea. Not even a bad idea, but any idea can be the undoing of someone, particularly someone with a lot of power. Oedipus clings to the idea that he couldn’t have married his mother, and he has all kinds of evidence to back up his claim, but in the end his denial has the better of him. Richard ends up denying to the very last that he’s been deposed, but Henry IV ends up getting one over him, when even Richard’s former associate Aumerle ends up murdering him. It’s not even that complex in terms of intrigue, and certainly less complex than what really happened, and it maintains the basicness of human nature. The two main principles are

The genius of Shakespeare is often the simplicity of these basic ideas of motivation, but paired with such deep characterization that we forget how simple it is. Even something as seemingly complex as King Lear is just simplicity paired with enough depth that we are drawn in. Shakespeare had to do that to keep an audience for 2.5 hours. I defy anyone who makes the argument that the difference was between Shakespeare’s audiences and modern audiences, as if the people who attended The Globe were so much more literate. I haven’t found any evidence that they were. The plays are just that good. A lot of movies these days just aren’t.

Advertisements