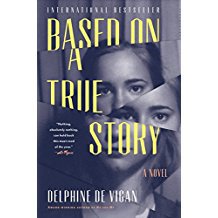

The latest book from the award-winning French novelist Delphine de Vigan is an elegant tale about a woman’s descent into her own personal hell. Part psychological thriller, part horror story, it pays special homage to Stephen King, but also to dozens of other contemporary writers. It’s a book about violence in its subtler forms, plagiarism being the most benign. The author, in fact, steals openly from other writers’ works, as do her characters, some to more brutal ends than others. Mostly, though, the book is about writer’s block run amok.

The latest book from the award-winning French novelist Delphine de Vigan is an elegant tale about a woman’s descent into her own personal hell. Part psychological thriller, part horror story, it pays special homage to Stephen King, but also to dozens of other contemporary writers. It’s a book about violence in its subtler forms, plagiarism being the most benign. The author, in fact, steals openly from other writers’ works, as do her characters, some to more brutal ends than others. Mostly, though, the book is about writer’s block run amok.

Although the obvious King analogy, The Shining, is not explicitly mentioned, Misery is: “If I write this novel for you, will you let me go when it’s done?” The full significance of this quotation, which appears in the epigraph to Section III, unravels as neatly as does the narrator’s sanity, while the plot, in the final section, descends a bit clunkily into Misery Redux. The face-off that results, however, is nowhere near the end of the story. “Which of the two of us had the upper hand I couldn’t have said,” remarks the narrator in the middle of the fray – a question that remains open for at least the rest of the narration, and arguably beyond.

“Not a nuance is missed or a detail wasted as the pieces, ultimately, fit perfectly together in a conflict between creation and self-destruction.”Which two of “the two of us” the narrator means – storyteller, superego, mystery woman, author, id, reader – remains unclear. Contraries meet, mysteries deepen, and the author’s final stroke of genius may be to let the reader in on the “truth,” while leaving her protagonist in the dark. (Emphasis on may.) Meanwhile, not a nuance is missed or a detail wasted as the pieces, ultimately, fit perfectly together in a conflict between creation and self-destruction, illusion and reality. In a few places in the book, this classic kind of scuffle, in the French way, can border on the philosophically abstract – but amazingly, it is never boring.

Delphine de Vigan

Delphine de Vigan

Central to the entire intrigue, and uppermost in the story’s attraction, is the seductive mystery woman dubbed “L.” by the narrator. I must confess it took me a while to remember that this is simply a variant spelling of the French “elle,” or “her.” Once this is clear, of course, one thinks of the movie Elle (based on the French novel Oh . . . by Philippe Djian), featuring a luminous Isabelle Huppert. In fact, I had already been thinking of Huppert, as L. seems written precisely with the actress in mind. L. is the protagonist’s mysterious doppelganger, a caring, loving, controlling, chilling presence who effectively anchors the plot. Roman Polanski, in his recent film adaptation of the novel (which was screened out of competition at Cannes, and is apparently something of a disappointment) chose a different actress, and reportedly added his own twist to what is already a twisty story.

“What should not be left unsaid is the most fundamental pull of this story: its universal female experience.”As with any good mystery, hints and head fakes abound, but in this story, there are also wide arcs of illusory certainty as to what’s “really” going on. The first half of the novel kept me spellbound, but the key to enjoying the whole is to read it a second time, when the threads mesh and the full impact of the author’s inventiveness becomes clear. What should not be left unsaid, however, is the most fundamental pull of this story: its universal female experience. The narrator – a careerist, a mother, a middle-aged empty-nester, a broken heart – writes of longing, despair, fear, and joy in a way that will be sympathetic and familiar to any woman in this century who picks up the book. The book taught me a lot about the writing process, but also about the mysteries and vagaries of the female heart – my own.

Ω

Share this: