The Battle of Mogadishu was an intense, lopsided engagement between the U.S. military and Somalian militia that cost hundreds of lives, wounded many hundreds more, led to the failure of efforts to stabilize the country, and was swiftly forgotten by many. It was a significant, if Phyrric, battle in which overwhelmed U.S. forces outfought their enemy by a large multiple in terms of killed and wounded, and yet had to quit the field. Mark Bowden would write a best-selling book on the battle in 1999, and director Ridley Scott and an ensemble cast would dramatize it two years later in an especially memorable story of modern war: Black Hawk Down.

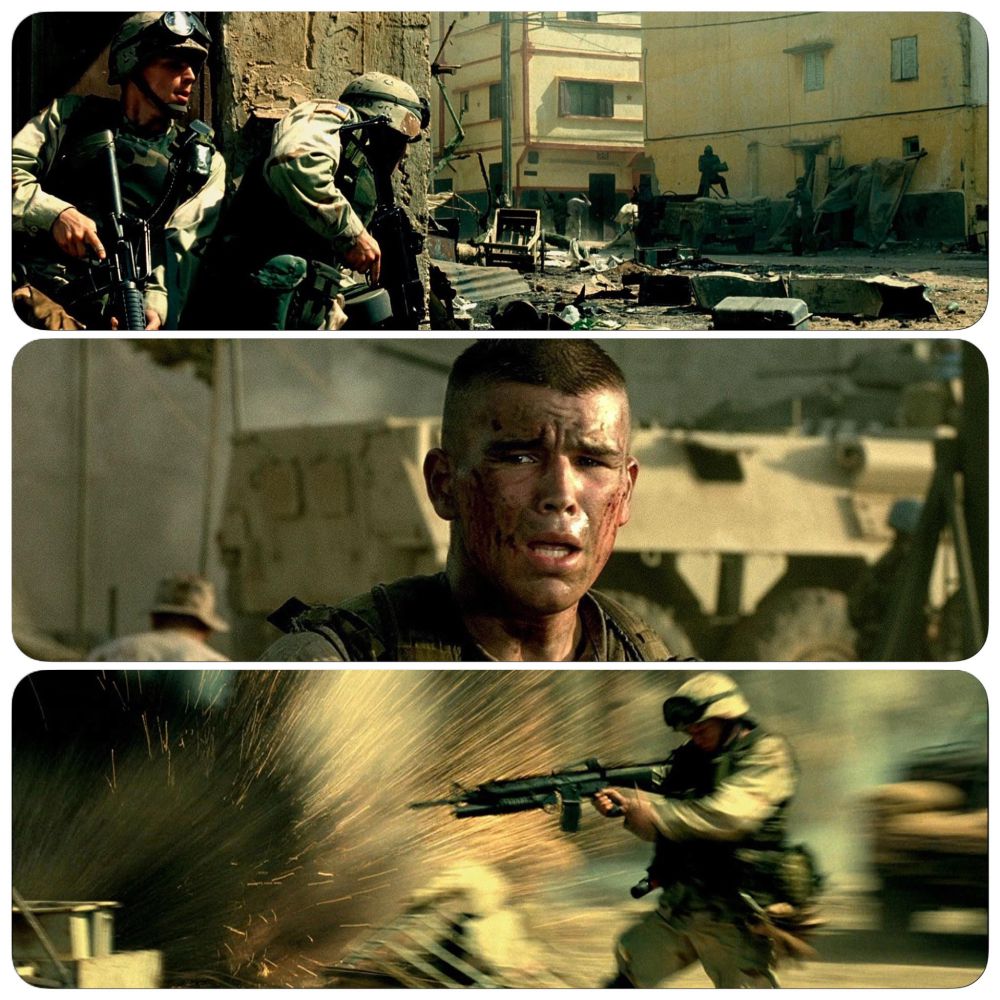

Somalia, 1993. As the country descends into civil war, warlords disrupt UN efforts to provide food and crucial supplies to civilians. The United States, fresh off its victory in the Gulf War, plans a series of raids in the capital of Mogadishu to capture the top aides to warlord Mohamed Farrah Adid in the hopes that it might help restore enough order to protect the UN humanitarian mission. U.S. commanders send a rotorborne force of Army Rangers, Delta Force and Special Operations aviators to get the job done, and while the initial raid goes according to plan, it doesn’t last. Injuries complicate the extraction, and soon two Black Hawk helicopters are shot down as hundreds of hostile militia swarm the trapped U.S. forces. Over the next 24 hours, the soldiers stuck in the city must battle block by block through hostile territory in an effort to rescue their fallen comrades, stay alive, and get the hell out of what has become the world’s deadliest shooting gallery.

This movie landed at a strange time, hitting theaters just over three months after the 9/11 attacks. Americans were still walking around numb from the event, and surely more than a few went to the theaters to see a story of U.S. forces tearing it up in a distant, sandy part of the world. But those looking for a jingoistic hero story were going to be a bit disappointed; they got a riveting and highly technical depiction of American military prowess and professionalism, sure. But it also depicted what it looks like when you bite off more than you can chew. Given what would unfold in the years to follow, Black Hawk Down has a strangely prophetic feel to it. It has aged well already. It will continue to do so, mainly because it stays out of the politics of why the soldiers were in Somalia in the first place. It focuses instead on the brotherhood forged by surviving enemy fire, and taking life as a matter of instinct. All kinds of people go into war. Only two come out of it: the dead and survivors. Nobody makes it through unchanged.

Black Hawk Down covers a lot of narrative ground as it follows the U.S. forces split apart during their frantic battle to stay alive, jumping from group to group, telling a series of smaller, interconnected stories that range from the tragic to the heroic to the comical—a collection of moments of truth both high and low. And while the movie centers on the struggles of Chalk Four—a team led by a fresh-faced staff sergeant tasked with rescuing some of the downed aviators—the peripheral dramas feel especially compelling. Every scene suggests that the potential to be in the wrong place at the wrong time is everywhere, and there isn’t a whole lot one can do about it except to fight hard and get your people home.

A convoy of trucks drives around the city repeatedly trying to get through blockades in an effort to rescue stranded soldiers, and the sergeant leading it at one points gripes as if he’s stuck in LA traffic. A pair of machine-gunners take the long way through town, unable to communicate because one accidentally burst the other’s eardrums by firing too close to his head. A flight of gunships offers breathtakingly close fire support in a lethal show of skill, technology and sheer guts. And then our central soldiers, who have already endured and survived so much, must withdraw from the city on foot, all while a crowd of hostile militia swarms in the background, and stray bullets continue to zip by.

The biggest moment of truth is when it becomes clear that one of he crashed choppers is totally cut off from rescue, so a pair of Delta Force snipers—SFC Randy Shughart and MSG Gary Gordon—volunteer to be inserted at the site from the air in an attempt to rescue injured aviator Michael Durant. Shughart and Gordon are told this is most likely a one-way trip, and they go without hesitation or bravado, just the reflex of years of intense preparation. On the ground, the situation quickly goes south, and Shughart and Gordon fight hard but are soon slain defending Durant, who is taken prisoner. Moments before Durant is captured, one of the snipers hands him a holdout weapon and wishes him luck, even though and they both know there isn’t enough luck in the world for either of them now. Both snipers would receive posthumous Medals of Honor for their bravery in a telling example how in war, the biggest heroes often are the ones who don’t come back.

And yet, when we get to the epilogue, when the surviving soldiers take stock of their battle, there are those among them who go back into the city. Not for revenge, and not for thrills, but because they are professionals, and there is still work to be done. As one Delta trooper grabs a quick bite to eat before a bewildered Ranger, he just shrugs. This is war, man. That’s all it is. It is hell for everybody, but it would seem that not everybody suffers it the same way, or to the same extent. There’s just no way to tell until it’s too late.