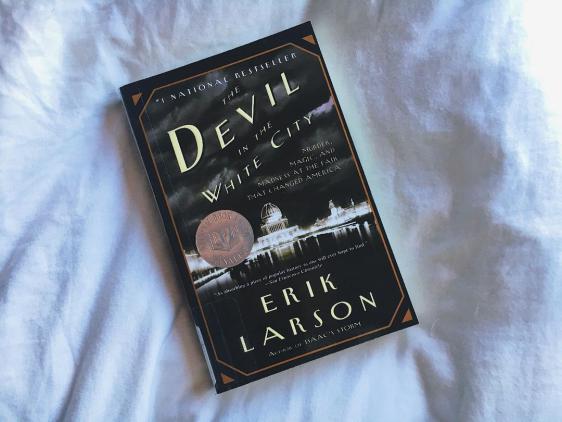

Other than memoirs, I tend to read mostly fiction – short stories, novels, poetry. I still carry some odd internalized misconception that nonfiction is always about something boring and technical, a misconception I know to be false but nonetheless continue to harbor for reason unknown. It probably has something to do with the fact that I feel like it’s my life’s mission to prove how fiction writing, and other “non-empirical” arts can, and often do, have concrete effects on our world – the never-ending battle every liberal arts supporter has found themselves taking part in at some point.

However, Erik Larson has single-handedly changed my mind. Not all nonfiction is monotonous, overly-technical, boring facts written in a staccato matter-of-fact tone. Larson’s The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair That Changed America reads like a fictional mystery novel, despite it being categorized as historical nonfiction.

A few months ago I was looking into moving to Chicago. In addition to letting me crash with her, and spending her weekend running all over looking at apartments with me, my friend Sarah recommended this book to me. She said even if I didn’t end up moving to Chicago I should read it because it was just THAT good. The book alternates between describing the architects and the seemingly impossible obstacles involved with putting together the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, and the grisly, meticulous acts of Herman Webster Mudgett, better known as H.H. Holmes – the man for whom the term “serial murderer” was coined.

Admittedly, I was a bit more interested in the H.H. Holmes chapters, and even Sarah said that some people skip the Fair chapters entirely and just read about Holmes; however, despite a few architecture-heavy moments, the descriptions of the fair were some of my favorite parts of the novel. Larson draws from first-hand accounts and pulls descriptions from letters, newspapers, personal diaries, and anything else he could get his hands on. And I mean that literally, which is why after just reading one of his books I would categorize Larson as one of my favorite writers – in his Notes and Sources section, Larson says:

“I do not employ researchers, nor did I conduct any primary research using the Internet. I need physical contact with my sources, and there’s only one way to get it. To me every trip to a library or archive is like a small detective story. There are always little moments on such trips where the past flares to life, like a match in the darkness. On one visit to the Chicago Historical Society, I found the actual notes that Prendergast sent to Alfred Trude. I saw how deeply the pencil dug into the paper” (395-396).

Up until I read this, my primary (and possibly only) issue with Larson’s writing was how many authorial liberties he seemed to take when it came to recreating certain murder scenes for which no sources exist, being that the only sources that could exist were murdered, (duh). However, Larson says he did the best he could with what he had, studying Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, and utilizing outside experts that were able to educate him on things like “the character of chloroform and what was knows at the time about its effect on the human body” (395). Larson’s transparency as well as his extremely thorough additional research has more than allowed me to look past these “how would he know?” moments.

H.H. Holmes infamous “murder castle”. He designed the building himself, creating passages that lead to nowhere and rooms into which he could pump deadly gases to kill his victims in their sleep.

H.H. Holmes infamous “murder castle”. He designed the building himself, creating passages that lead to nowhere and rooms into which he could pump deadly gases to kill his victims in their sleep.

As I mentioned before, Larson defied every misconception I had about nonfiction works, largely because of how much humor he’s able to inject into his writing. In an anecdote about a young couple that met at the fair he quotes a letter from author and journalist Theodore Dreiser to Sara Osborne White: “I went to Jackson Park and saw what was left of the dear old World’s Fair where I learned to love you” (382). He immediately follows this with an extremely blunt but very funny, “He cheated on her repeatedly”. Erik Larson: making the romantics swoon only to stop them short one sentence later.

The novel itself educates the reader about the magic of the fair and the horror of H.H. Holmes without simply rattling off facts and statistics. Among the empirical data, from first hand accounts Larson shares the many “firsts” that were introduced at the fair:

“They heard live music played by an orchestra in New York and transmitted to the fair by long-distance telephone. They saw the first moving pictures on Edison’s Kinetoscope, and they watched, stunned, as lightning chattered from Nikola Tesla’s body. They even saw more ungodly things – the first zipper; the first-ever all-electric kitchen, which included an automatic dishwasher; and a box under purporting to contain everything a cook would need to make pancakes, under the brand name Aunt Jemima’s. They sampled a new, oddly flavored gum called Juicy Fruit, and caramel-coated popcorn called Cracker Jack. A new cereal, Shredded Wheat, seemed unlikely to succeed – “shredded doormat” someone called it – but a new beer did well, winning the exposition’s top beer award. Forever afterward, its brewer called it Pabst Blue Ribbon” (248).

The Chicago World’s Fair of 1893

The Chicago World’s Fair of 1893

One of my favorite aspects of Larson’s writing is his affinity for setting up his reader with something seemingly non-spectacular, and then name-dropping some insanely well-known person or event like he’s pulling a coin from your ear. For example, at one point he’s discussing how “chance encounters lead to magic” at the fair. He mentions “Frank Haven Hall, superintendent of the Illinois Institution for the Education of the Blind” and talks about how he invented a device that was able to type in Braille and was introducing his newest model at the fair. Larson continues with, “As he stood by his newest machine, a blind girl and her escort approached him. Upon learning that Hall was the man who had invented the typewriter she used so often, the girl put her arms around his neck and gave him a huge hug and kiss”. The passage ends, “Forever afterword, whenever Hall told this story of hoe he met Helen Keller, tears would fill his eyes” (285).

Erik Larson paints the World’s Fair in such a way that the reader can’t help but feel slightly cheated that they weren’t there to experience the magic themselves. His account of Holmes’s atrocities are just as horrific as they are addicting. Overall, I came away from Devil in the White City with the sentiment that if all historical events and people were taught in such a way, I might have been a hell of a lot more interested in nearly all of my History classes.

Other works by Erik Larson that I can’t wait to get into include:

- In the Garden of Beasts: Love, Terror, and an American Family in Hitler’s Berlin

- Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania

- Isaac’s Storm: A Man, Time, and the Deadliest Hurricane in History

- Thunderstruck

- Lethal Passage

- The Naked Consumer

I’ll have another book review up next week where I’ll talk about the genius that is Gillian Flynn’s Dark Places.

As always, thanks for reading!

-k

Advertisements Share this:

![[Music Release] Luhan drops new single “Catch Me When I Fall” after announcing he will be going on break](/ai/025/163/25163.jpg)