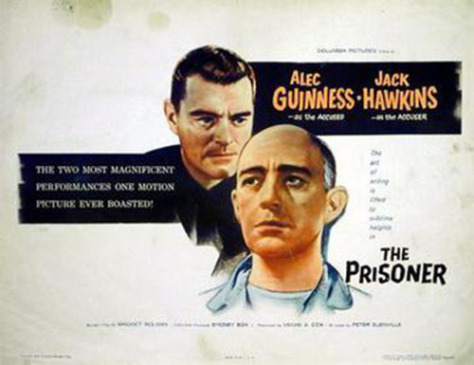

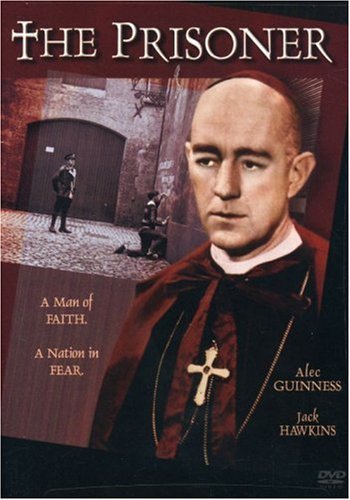

Unlike Peter Glenville’s later (and greatest) movie “Becket” (1964), another movie about subordinating Church to State, “The Prisoner” (1955, adapted by Bridget Boland from her own play about Hungarian cardinal József Mindszenty), did not retain the names of the historical-character antagonists: just the cardinal and the interrogator in an unnamed Eastern European country the regime (actually, I don’t think “communist” is mentioned either) of which cannot tolerate any organization or assemblage not under its overt or convert control. (This is a phenomenon in the Leninist crony capitalism that is the Chinese Communist Party ruling the world’s most populous country of the present, btw, as well as North Korea and postcommunist Russia.)

The cardinal (played by Alec Guiness) was a hero of the resistance to Nazi occupation and had not been broken by the physical torture of the Gestapo. The interrogator (played by Jack Hawkins [Land of the Pharaohs, Bridge on the River Kwai]) was a less prominent player in the resistance, was never captured, and has never failed to convince a prisoner to confess whatever absurdities have been prepared for trial of an enemy of the state.

The very British-sounding antagonists have a very British-sounding class dynamic at play, the interrogator a child of the elite, the cardinal having been raised by a single mother who worked in the fish market and was of “easy virtue” (that is, bedded many different men). It seems to me that the self-confidence based on class plays too large a part in the eventual success of the unfailingly polite and sometimes positively genial interrogator. (In that the play and movie are a reflection on the confessions after long imprisonment and torture of Cardinal Mindszenty, the only question is how this was brought about, so I don’t think that it is a plot-spoiler to telegraph the eventual public confession of the self-loathing prelate.

It takes a long time for the interrogator to figure out what the cardinal’s mental weakness is… and little time to exploit it, once found. Good as Hawkins is at underplaying (and while I can recall roles in which he was unconvincing, these were never the result of overplaying), I am not convinced at the interrogator’s disgust. It seems to me to be there mostly to make him less than a total villain to the audience. (On the other hand, I do believe that to succeed, he has to know his quarries better than they know themselves.)

Alec Guiness, repeating a role he had performed under Glenville’s direction on the London stage, was a very great actor in a wide variety of roles (of widely varying ethnicity) and had a very, very showy role as the irony-noting arrogant captive, the captive being driven crazy by the book, and as the willing condemner of himself. The cardinal is steadfast in his embrace of abjection, so there is a continuity between first and last (as there is in Peter O’Toole’s penance at the end of “Becket”).

Both the actors, and the hammy Wilfred Lawson as the jailer, are very good. There is a ridiculous peripheral love story between a prison guard (Ronald Lewis) and a Catholic young woman (Jeanette Sterke) whose husband has fled the country, and the exteriors look good (if not central European). The problem for me is that I don’t believe the flaw the interrogator exploits. I can believe there is the weakness in the cardinal, but not that it could be so easily used once discovered. Also, I am not convinced that either the cardinal or the interrogator believes in the Truth as their opposing sides believe themselves to have a monopoly of. (There is no philosophical discussion between them, not even any about how the church should be used by the state… or what should not be rendered unto the communist Caesar…)

The DVD includes no bonus features, only some trailers to better known, award-winning movies in which Hawkins and/or Guiness appeared (Ben Hur, The Bridge on the River Kwai, Lawrence of Arabia).

BTW, both the Venice and Cannes film festivals refused to show the movie for fear of offending cultural officials of Eastern bloc states. And after the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian revolt in 1956, Cardinal Mindszenty spent many years in the US Embassy in Budapest and refused to give up his position as prelate of Hungary even after he was relocated to Vienna.

I am one of the relatively few who liked/admired Glenville’s last movie, the 1966 adaptation of Graham Greene’s The Comedians (with Guiness and Peter Ustinov et al. as supporting characters to Taylor/Burton). Before that, he made a leaden comedy with Guiness, “Hotel Paradiso” (1966). In addition to “The Prisoner” and “Becket,” Glenville directed “Me and the Colonel” (1958), “Term of Trial” (1962) and “Summer and Smoke”(1961), all primarily conflicts between two characters. I wish he’d had Greene adapt “The Prisoner.” I suspect that would have increased the plausibility of the characters.

©2017, Stephen O. Murray

Advertisements Share this: