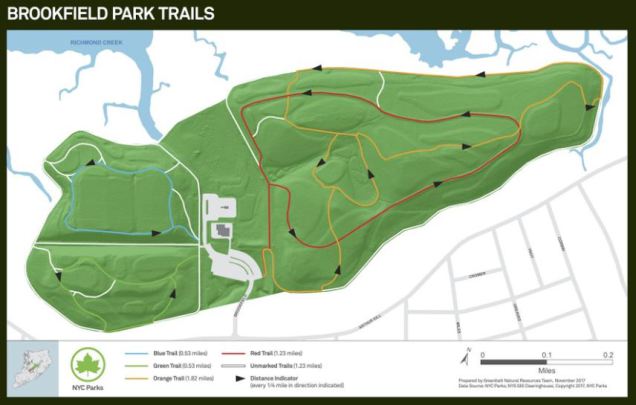

On December 12, 2017, NYC Parks celebrated its 30,000th acre with the opening of Brookfield Park on Staten Island. This 287-acre property is a former landfill transformed into a hilly prairie landscape overlooking Richmond Creek. For the purposes of this blog, I traveled to this new park in search of the brook for which Brookfield may be named.

A day after its official opening this 258-acre park still had an “authorized personnel only” kind of feel. Not too many bikes or joggers to be found here on a snowy morning.

First Hint of Stream

The main entrance to Brookfield Park is at Arthur Kill Road and Brookfield Avenue, leading me to believe that perhaps there’s no brook at all here and the park is named after the avenue. Brookfield is a common name for a suburban street, given to evoke pastoral feel. But what if the avenue was named after a long-gone brook?

The first hint is past the park’s parking lot at the modernist Eltingville Pumping Station. It has the look of an isolated tundra outpost. As I’ve seen before, wherever there’s a pumping station there used to be a stream. This set of buildings predates the park and is now a DEP enclave enveloped by parkland.

Brook in the Park

To the north of the pumping station, the park’s access road curves at the border fence that separates Brookfield Park from the marshland section of LaTourette Park that follows Richmond Creek. In the background is the bridge carrying Richmond Road across Richmond Creek and behind it are the manmade hilltops of Freshkills Park, an even larger former landfill-turned-park. In the foreground, a creek emerges from a culvert and meanders towards Richmond Creek. Could this be the namesake brook for Brookfield Avenue, and in turn Brookfield Park?

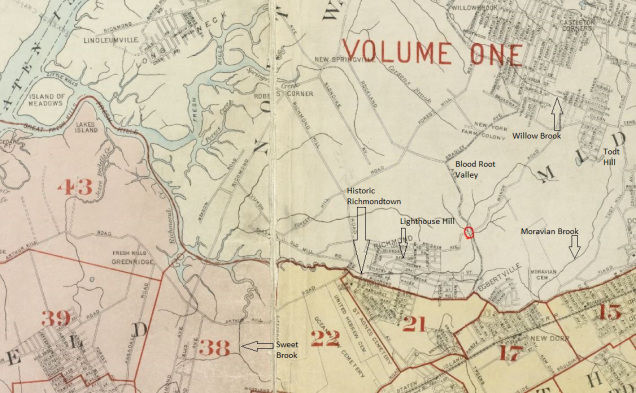

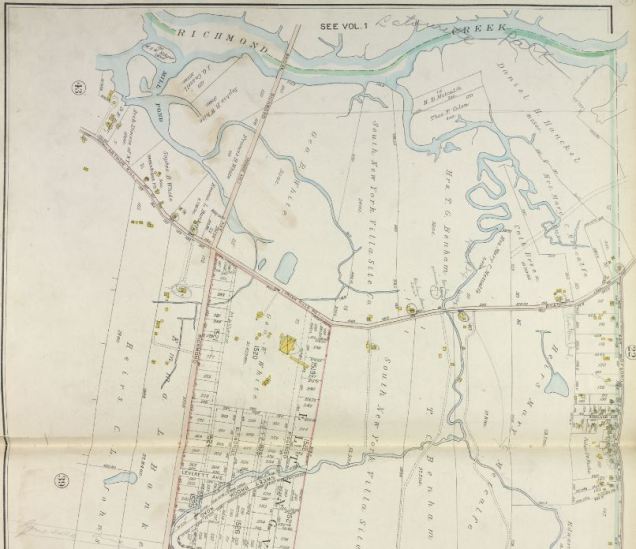

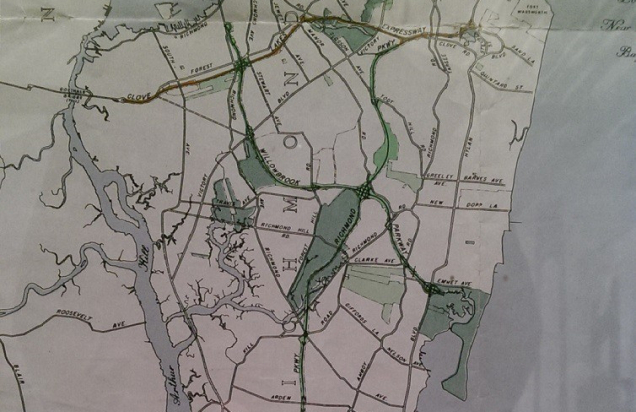

The 1917 G. W. Bromley Atlas offers the answer, showing Sweet Brook flowing into Richmond Creek at page 38, just north of Arthur Kill Road and east of Richmond Road on land that corresponds to today’s Brookfield Park.

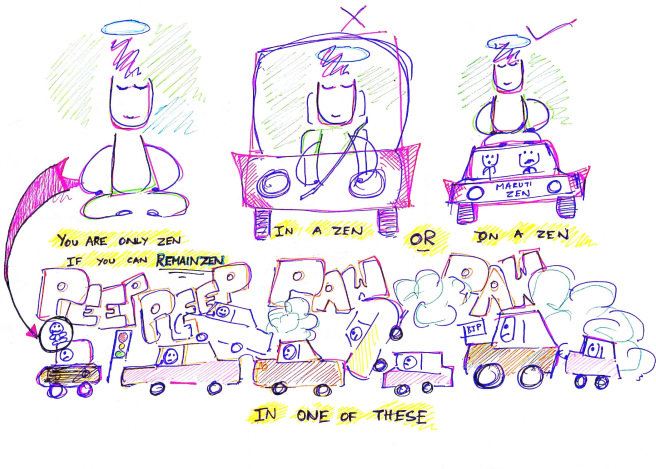

A look at page 38 shows only two completed roads across this area: Arthur Kill Road and Richmond Avenue, everything else being either paper streets, farms, and undeveloped properties. In the planned Eltingville development is the grid-defiant Sweet Brook Road. It’s still there today following a portion of Sweet Brook that had not been covered.

Sweet Brook Bluebelt

Under the DEP Bluebelt program, portions of Sweet Brook that have not been developed were preserved as a naturalistic storm water channel flowing through the Annadale, Eltingville, and Great Kills neighborhoods.

At Sweetbrook Road and Ridgewood Avenue, the brook goes into an underground culvert that proceeds north beneath Abingdon Avenue towards Brookfield Park. It flows beneath the former landfill and emerges at the park’s northern boundary, a few yards shy of its confluence with Richmond Creek.

In its design for Bluebelt streams, the DEP used historically-themed elements such as stone embankments and bridges, and stone name plaques identifying the streams.

In its design for Bluebelt streams, the DEP used historically-themed elements such as stone embankments and bridges, and stone name plaques identifying the streams.

If I were to work at DEP, I’d have the agency follow NYC Parks’ Historical Signs program by installing explanatory signs on DEP properties such as Bluebelts, reservoirs, dams, and pumping stations. The stone plaque for Sweet Brook is a start, but I believe that the more information there is for the public, the more it is invested and interested in caring for the city’s infrastructure.

The full course of Sweet Brook is deserving of a separate blog post, which I hope to do in the future.

Estuary at Brookfield

At the northern edge of Brookfield Park, Richmond Creek gives off a slightly salty smell but not as salty as the ocean. In this section it is an estuary where the tides of Richmond Creek mix with fresh water flowing in from the creek’s sources.

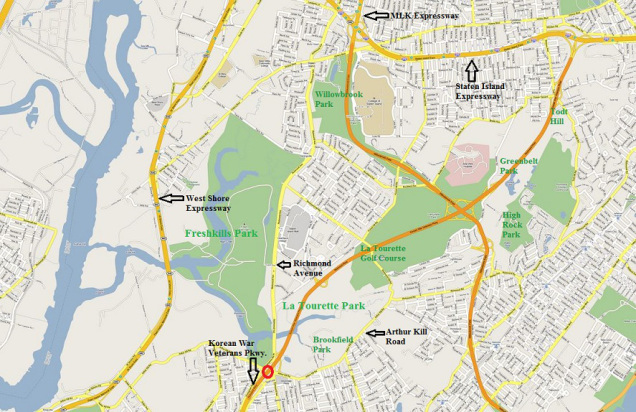

It is a rich habitat that unfortunately was degraded by nearly a half century of trash dumping. Although it has an undisturbed and silent quality, it could have been worse. In the 1960s, Robert Moses proposed extending Richmond Parkway along its eponymous creek towards Todt Hill where it would merge with Staten Island Expressway.

Mapmaker Vanshookenraggen, known for plotting the city’s unbuilt subway lines also made a map for Staten Island’s unbuilt roads, shown above in orange. Presently, the parkway’s northern terminus is at Arthur Kill Road, where a dead-end bridge runs above Richmond Avenue on its way into the park. Had it been built, this highway would have mercilessly sliced through La Tourette Park’s wetlands and golf course, the forested knob-and-kettle terrain of the greenbelt and its Boy Scout camp, and past the summit of Todt Hill.

Near the “buckle” of the Greenbelt it was to have a sprawling cloverleaf interchange with Willowbrook Expressway, an unbuilt road that was to run from Bayonne Bridge to Great Kills Park on the South Shore.

Today, these two highways are a faint memory, with the competed portion of Richmond parkway carrying the name Korean War Veterans Parkway and the completed section of Willowbrook named after Martin Luther King Jr. The rights-of-way and green shoulder spaces intended for these roads instead became the Staten Island Greenbelt, a set of parks connected by thin green corridors. As it is adjacent to La Tourette Park, Brookfield can also be considered part of the Greenbelt, along with Freshkills, Willowbrook, High Rock, and Great Hills parks.

Landfill

In 1966 the city began dumping municipal waste on the Brookfield site with little oversight the landfill also illegally accepted industrial toxic waste. A federal investigation in 1982 resulted in the conviction of a Sanitation official and a hauling operator. With the support of the advocacy group Earthjustice, the Northern Great Kills Civic Association sued the city and received a settlement where the state and city paid $256.4 million for remediation of the property.

The dumpsite was capped and covered with grass ahead of its transformation into a park. Unlike the typical large park that has its sports fields, playground, and picnic areas, the western half of Brookfield is intentionally left empty to allow future generations to determine what they wish to have at this park.

It’s an unusual sight to see so many city officials cutting the ribbon in what appears to be the middle of nowhere but keep in mind that the parking lot at Brookfield Park has 200 spaces. This shows that sooner or later the public will “discover” this park and explore its “out of town” landscape.

Internal Wetlands

Between the manmade mounds the park’s designers created naturalistic pools and brooks that further enrich the park’s name. With 76,000 plants and 17,000 trees planted, the bald terrain will soon see foliage and a diverse flora of 27 species.

As the mounds cannot collect rainwater, water from the mounds flows down the slopes to these collection pools before draining into the Richmond Creek watershed. Like the ponds of Central Park, they are manmade and nameless for now. With the planned development of this park in the coming decades, the trails will have names as will its waterways.

So for now, put on good running shoes, take your bird watching binoculars and enjoy the city’s newest public park.

Advertisements Share this: