by Rick Krueger

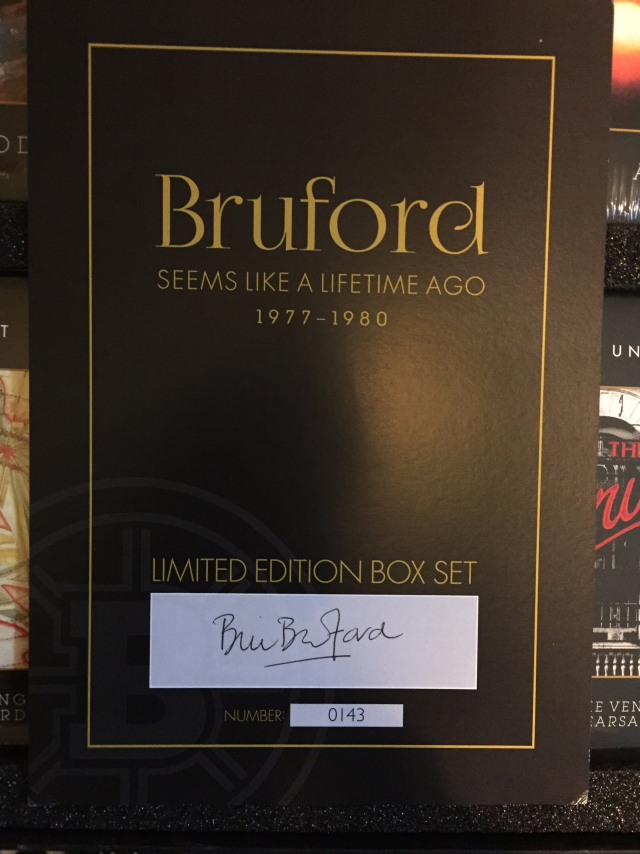

I think it’s fair to say that this 8-disc set is going to be my reissue of the year. It’s pure delight from first to last, covering three brilliant studio albums, two distinct live sets (one previously unreleased) and a fascinating batch of rough-draft outtakes — all spearheaded by paradigmatic progressive rock drummer Bill Bruford.

1978’s Feels Good to Me served as a sparkling mission statement, Bruford’s first solo album following fruitful years in Yes and King Crimson and sideman stints with Genesis, Gong, and National Health. Bruford and keyboardist Dave Stewart’s compositions ranged from fizzy, animated bebop (“Sample and Hold” and “If You Can’t Stand the Heat”) to surprisingly rich lyricism (“Seems Like A Lifetime Ago,” “Either End of August” and “Springtime in Siberia”), with whimsically pompous prog tossed in on “Beelzebub” and the title track. The core band of Stewart, Allan Holdsworth on guitar and Jeff Berlin on bass proved empathetic and audacious, giving a fresh feel to Bruford’s idiosyncratic take on jazz-rock fusion. Kenny Wheeler (flugelhorn) and Annette Peacock (languidly swinging vocals) contributed memorable guest-star turns.

Then, unexpectedly, a new opportunity popped up: U.K. suddenly reunited Bruford (who brought Holdsworth along) and King Crimson bassist/singer John Wetton for another shot at the mass market, with Eddie Jobson slotting in as keyboardist and main composer. A whirlwind year of recording and touring culminated in Jobson and Wetton dumping Holdsworth, already notorious for his unwillingness to repeat himself, to pursue a more straightforward rock direction; Bruford then opted to bail out.

The result was 1979’s One of a Kind, the first effort by Bruford the band, which more than lived up to its title. Now a self-contained quartet, Bruford, Stewart, Berlin and Holdsworth produced a dynamite set, still jazz-inflected but definitely rocking harder than Feels Good to Me. The opening “Hell’s Bells” had it all: a 19/8 synth riff from Stewart paired with Berlin’s bubbling bass line, Holdsworth pulling a head-spinning solo out of nowhere, Bruford making the convoluted rhythms sound effortless and elegant. The whole album is like that, with moment after moment of happy surprises; the Anglo-funk of “Five G” and “The Abingdon Chasp” sit comfortably alongside the keyboard-driven drama of the title track and “Fainting in Coils.” And two stunning pieces Bruford and Holdsworth brought with them from U.K. (“The Sahara of Snow” and “Forever Until Sunday,” with Jobson co-composing and guesting on violin) were the icing on the cake. It’s still one of my very favorite instrumental albums.

On the eve of Bruford’s first international tour, Holdsworth left to pursue his own thing, recommending “The Unknown” John Clark as his replacement. The Bruford Tapes is a rough-and-ready snapshot of the band’s second US gig, originally broadcast live on radio then released as an official bootleg in Canada. It’s thoroughly satisfying, with the group giving tracks from the first two albums extra muscle and drive. Clark more than holds his own, quickly finding a personal voice on guitar; Stewart’s synth, organ and piano work is fuller and edgier than in the studio; and Berlin and Bruford push the music harder, with adrenalized style and strength. Nifty new intros, interpolations and improvs on “Fainting in Coils” and “One of A Kind” just add to the thrills.

All this stirred up just enough success to get management and record company types fussing over Bruford’s next album. “You should get a producer that’s made hits” — so it was off to record with Ron Malo, an industry legend if not a household name. “You need vocals to have a shot at radio play” — good thing Bruford and Stewart had been writing lyrics and Berlin was willing to sing. 1980’s Gradually Going Tornado was the fine outcome. Though it foregrounds Berlin’s funky bass and endearingly loopy voice, it wasn’t a slick sell-out by any means. The lyrics stayed miles away from silly love songs, tackling media immersion (“Age of Information,”) troubled kids (“Gothic 17”), the nature of truth (“The Sliding Floor”) and the end of the world (“Plans for J.D.”). While the odd time signatures were fewer and the music’s quirky edges were sanded down a bit, the whole band turned up to 11 to compensate, with Stewart fuzzing up his Hammond organ and Clark leaning hard on his distortion pedal. “Q.E.D” and “Land’s End” provided the requisite instrumental epics, Berlin’s “Joe Frazier” yielded another delightful bebop work out, and “Palewell Park,” a luscious piano/bass duet, was Bruford’s most drop-dead gorgeous ballad yet.

The unreleased material in the box offers tantalizing glimpses of what could have followed. Live at the Venue shows the band both growing into the new material (with Berlin singing much more confidently) and continuing to revamp the back catalog (with more new surprises slotted into “Hell’s Bells” and “Five G”). The 4th Album Rehearsal Sessions by Bruford, Stewart and Clark showcase intriguing, fragmentary ideas; some of them wound up in the next version of King Crimson and Stewart’s avant-pop collaborations with Barbara Gaskin. But between the decline of the jazz-rock boom and the group’s ongoing inability to turn a profit on tour, Bruford the band’s future collapsed, and Bruford the drummer made the fateful decision to reconnect with a newly ambitious Robert Fripp.

For evidence of how highly esteemed Bill Bruford’s fusion period is, consider this: the first edition of this box (including nifty alternate and surround mixes of the first two albums by Jakko Jakszyk, as well as Sid Smith’s typically sympathetic and entertaining notes) sold out before the release date. But if this music sounds like it’s up your alley, orders for a second edition are being taken through November 30 at Pledge Music or Burning Shed, to be shipped in January. Given the sheer pleasure this set has brought me, I can’t recommend it highly enough.

- More