I have, in previous years, complained about the whiteness of Christmas books, so it is pleasant to be able to report *some* progress recently in British books that represent a wider variety of people. Some of the best multiracial holiday books are coming out of smaller presses, who in many ways have led the charge toward changing the culture of British children’s books; hopefully the leadership of publishers such as Stripes and Nosy Crow will spill over into the mainstream presses—many of whom continue to reproduce a nostalgia for white Christmases in the UK.

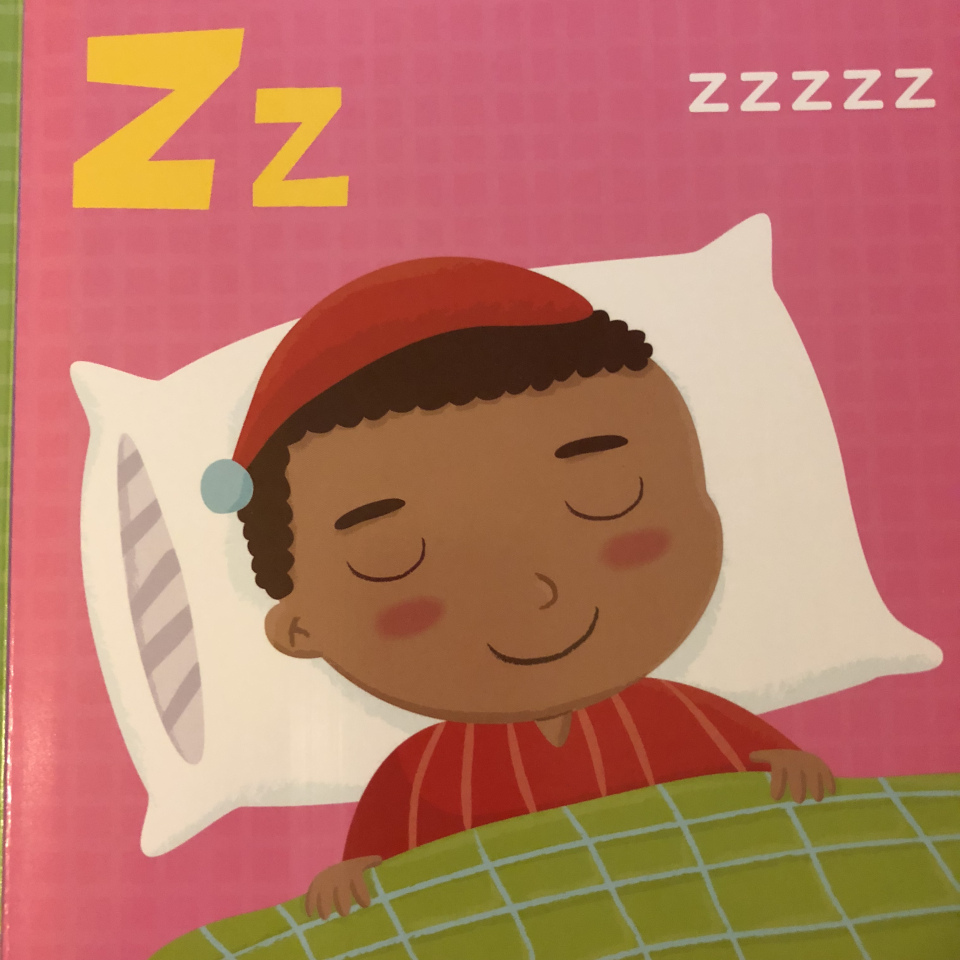

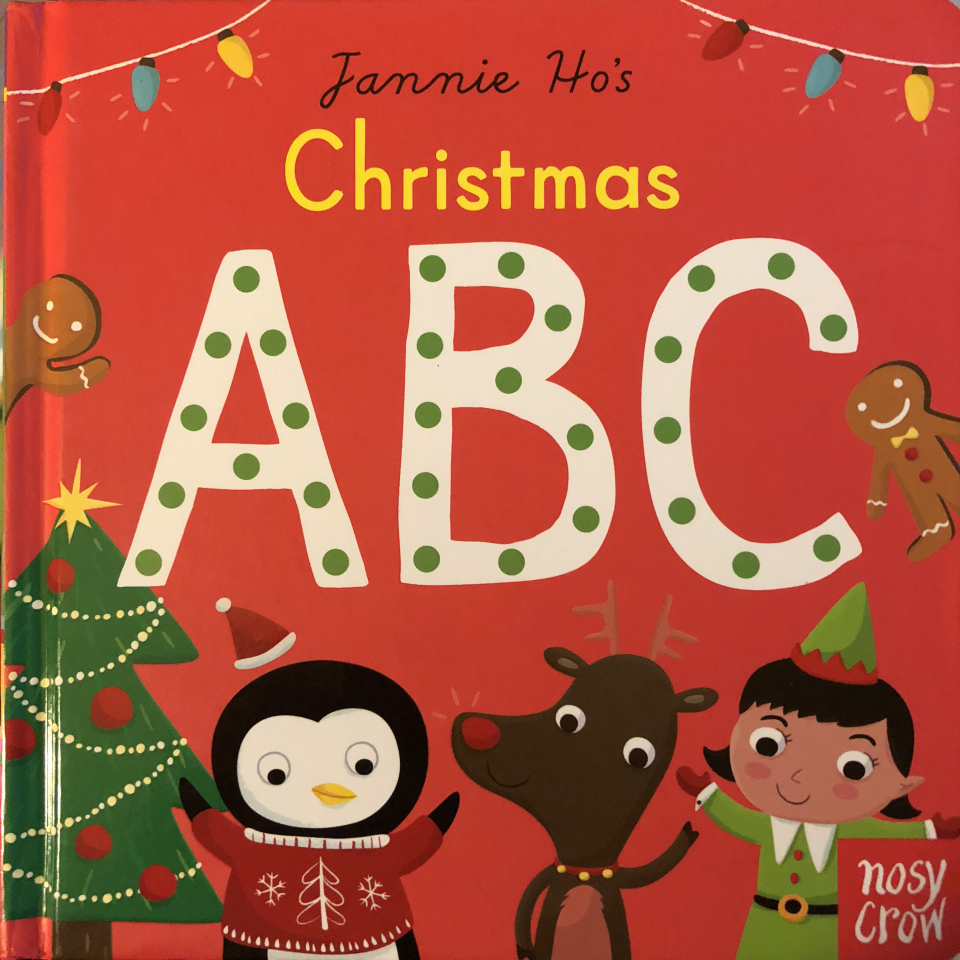

Jannie Ho’s Christmas alphabet includes all kinds of kids.

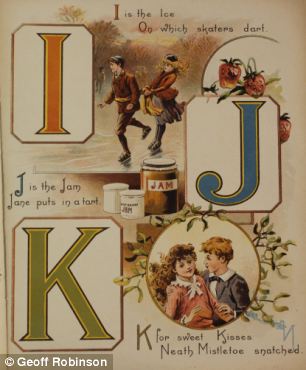

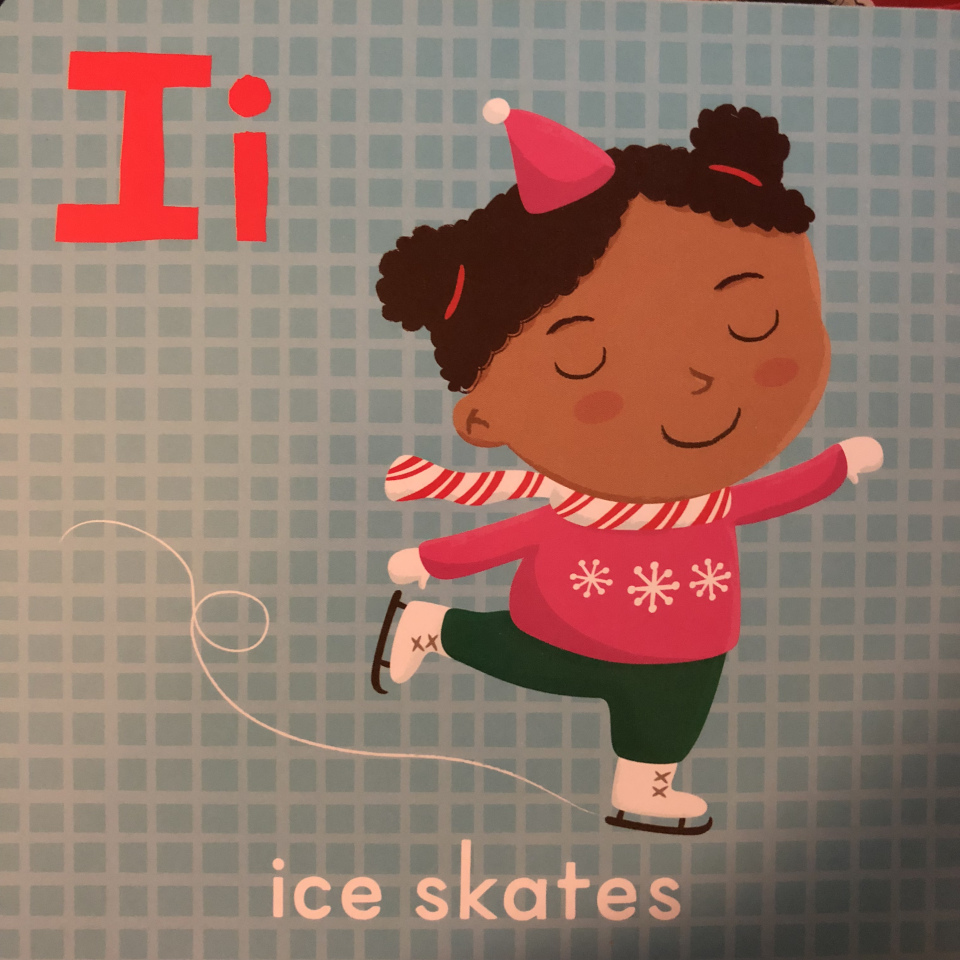

Since my last blog was about books for babies, I’ll start this one with a Christmas board book, Jannie Ho’s Christmas ABC (Nosy Crow 2016). Ho is a Boston-based illustrator who once worked for Nickelodeon, but Nosy Crow is a London-based publisher who won the British Bookseller’s children’s publisher of the year for 2017. The idea of an early concept book related to Christmas is hardly a new one; the children’s publisher Frederick Warne (who would later publish A Tale of Peter Rabbit and other Beatrix Potter stories) published The Father Christmas ABC in 1894 (http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2251033/The-ABC-Victorian-Christmas-revealed-Beautifully-illustrated-edition-childrens-book-discovered-University-library-P-plum-pudding-PlayStation.html), for example; and Little Golden Books (the “supermarket” bookseller of my childhood, known for The Poky Little Puppy and other books strategically priced and placed near the supermarket checkouts to entice weary parents with whinging children—not that my mother EVER had this problem of course) published The Christmas ABC by Florence Johnson, with pictures by Eloise Wilkin in 1962. These books often repeat ideas—B is for Bell in all three, for example—but the images change. The letter I is for ice in all three, and more specifically ice skating, but I’ll just leave the images to tell a story of a changing idea of who skates on the Christmas ice. Father Christmas ABC from 1894; this book was found in Cambridge University’s rare book room in 2012.

Father Christmas ABC from 1894; this book was found in Cambridge University’s rare book room in 2012.

Eloise Wilkins’ 1962 illustrations from Golden Book’s Christmas ABC.

Jannie Ho’s ice skater is different–and not just because of her Christmas sweater.

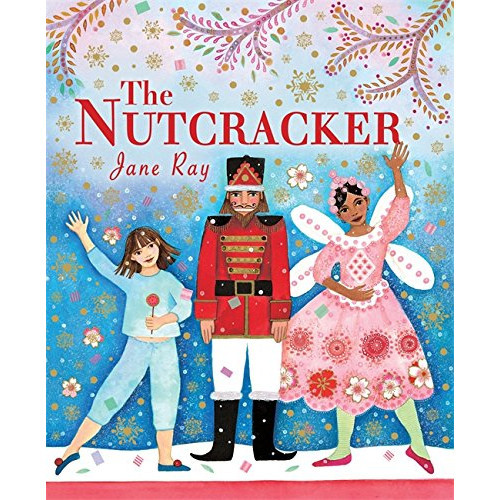

Jane Ray’s version of The Nutcracker (Hachette 2016) follows the general storyline of Tchaikovsky’s ballet, albeit in a modernized setting; Clara wears pajamas rather than the white lace-edged nightgown found in most ballet versions and she has multiracial friends who come to her party. These friends unfortunately disappear at bedtime (though the text implies they stay at the house). While it is true that in the ballet, Clara travels to the land of sweets with only the Nutcracker Prince to accompany her (not even her brother comes along), the final illustration in Ray’s book restores the unity of the white family only. Nonetheless, Ray’s Sugar Plum Fairy is Black, and has not only a prominent place on the cover, but an illustration all to herself in Ray’s book, making it a lovely change in the traditional Christmas story.

Tradition and change in Jane Ray’s version of Tchaikovsky’s ballet.

Christmas is a time for thinking about others, and for older readers in Britain, Stripes Publishing produced I’ll Be Home for Christmas in 2016 in part to help raise funds for Crisis, a charity providing services for the homeless across the UK. Prominent, award-winning writers contributed poems and short stories to the collection, including Benjamin Zephaniah and Sita Brahmachari. Zephaniah’s poem, “Home and Away,” opens the collection with a very different version of Christmas than that produced by nostalgia merchants, but one that forms a familiar experience for many readers. “I’d like to be home for Christmas/That’s where the rhythm wise hip-hop is,/ That’s where the rock and the jazz is/ The place where I dream happy/ Where I dance to sweet homemade reggae” (19). Zepahniah’s Christmas carols of a different color remind readers that different doesn’t mean unhappy or unChristmassy.

A time for giving–Benjamin Zephaniah and Sita Brahmachari are among the authors helping Crisis at Christmas.

These recent Christmas books make all the more disappointing a recently reissued edition of Terry Deary and Martin Brown’s Horrible Christmas (Scholastic 2016). The concept of horrible history is a fabulous one, and really draws the interest of many children (including, when she was younger, my own daughter) who are otherwise reluctant readers. BAME history has always proved a tricky subject for the Horrible History franchise, as I’ve detailed in other blogs, books and articles. While I’m aware that it might not be easy to make light of some BAME historical topics (probably a book on “Slimy Slavery” or “Egregious Empire” would raise eyebrows, to say the least), Deary and Brown often fail to include BAME people in British history even in noncontroversial ways. This is true of Horrible Christmas as well. The cover image provides a hint of what is between the covers, showing five white people (four of them men). The only image throughout the 96 pages of horrible Christmas trivia that includes people who aren’t white is a tiny one of a group of carol singers on page seven. They are about to have the door slammed on them.

Does tradition have to mean a White Christmas? Deary and Brown’s horrible holiday.

In fact, Deary and Brown’s book ends with a vision of Christmas future that is both a very white Christmas and a plea for helping others less fortunate—a page which recalls for me charity Christmas songs of the 1980s (yes, people around the world DO know it’s Christmas, even when they don’t or can’t celebrate it after all, you patronising so-and-so). I prefer the final image in Jannie Ho’s Christmas ABC, and leave it with you along with Clement Clarke Moore’s 1823 wish for a “Happy Christmas to all, and to all a good night.”