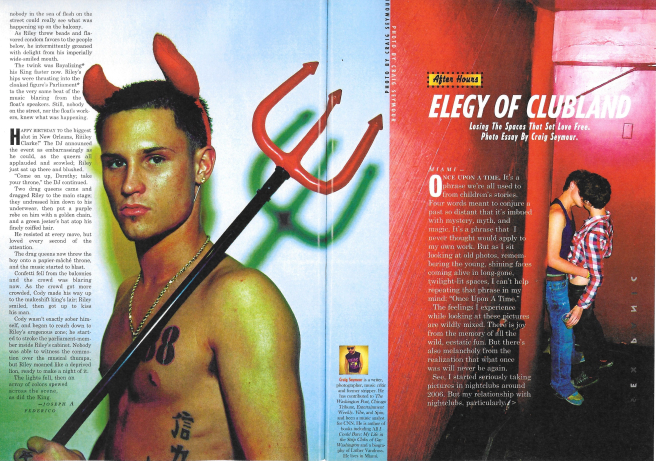

Elegy of Clubland by Craig Seymour

Once Upon A Time. It’s a phrase we’re all used to from children’s stories. Words meant to conjure a past so distant that it’s imbued with mystery, myth, and magic. It’s a phrase that I never thought would apply to my own work. But as I sit looking at old photos, remember the young, shining faces coming alive in long-gone, twilight-lit spaces, I can’t help repeating that phrase in my mind: One Upon A Time.

The feelings I experience while looking at these pictures are wildly mixed. There is joy from the memory of all the wild, ecstatic fun. But there’s also melancholy from the realization that what once was will never be again.

See, I started seriously taking pictures in nightclubs around 2006. But my relationship with nightclubs, particularly strip clubs, goes back much farther. The first gay club that I ever went to was a strip club, La Cage Aux Follies, in my hometown of Washington, D.C. As soon as I stepped in the door and entered the dark club where godly hunks danced under warm, red lights, I experienced a feeling of safety that came over me like a wave. It was the first time in my life that I felt fully secure in publically exhibiting my desire for other men without fear of reprisal, whether verbal or violent.

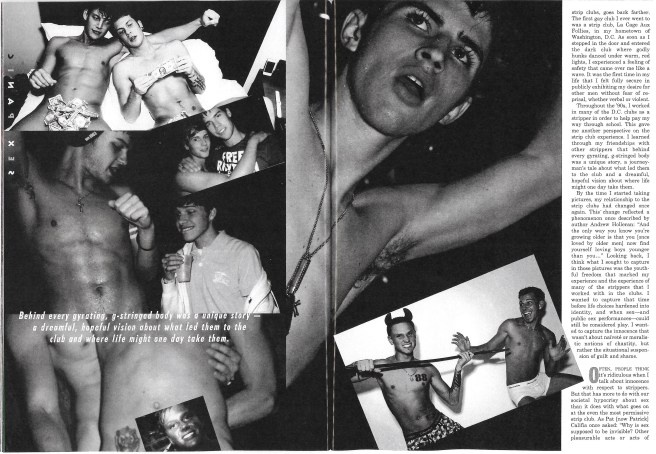

Throughout the ‘90s, I worked in many of the D.C. clubs as a stripper in order to help pay my way through grad school. This gave me another perspective on the strip club experience. I learned through my friendships with other strippers that behind every gyrating, g-stringed body was a unique story, a journeyman’s tale about what led them to the club and a hopeful vision about where life might one day take them.

By the time I started taking pictures, my relationship to the strip clubs had changed once again. This change reflected a phenomenon once described by author Andrew Holleran: “And the only way you know you’re growing older is that you (once loved by older men) now find yourself loving boys younger than you…” Looking back, I think what I sought to capture in those pictures was the youthful freedom that marked my experience and the experience of many of the strippers that I worked with in the clubs. I wanted to capture that time before life choices hardened into identity, and when sex—and public sex performances—could still be considered play. I wanted to capture the innocence that wasn’t about naiveté or moralistic notions of chastity, but rather the situational suspension of guilt and shame.

Often, people think it’s ridiculous when I talk about innocence with respect to strippers. But that has more to do with our societal hypocrisy about sex than it does with what goes on at the even the most permissive strip club. As Pat (now Patrick) Califia once asked: “Why is sex supposed to be invisible? Other pleasurable acts or acts of communication are routinely performed in public—eating, drinking, talking, watching movies, writing letters, studying or teaching, telling jokes and laughing, appreciating fine art. Is sex so deadly, hateful, and horrific that we can’t permit it to be seen?”

My photographic work, from its inception, has been committed to the idea that sex can be public and should be seen. But more and more, there are obstacles to this idea that don’t simply hinge on hypocrisy and moralism. Increasingly, spaces where gay men could engage in public sex—which runs the continuum from voyeuristically ogling a go-go boy to getting full-on biblical in a back room—are disappearing. Some of this is due to factors that have long impinged upon nightlife: sententious zoning laws; rising rents due to gentrification; homophobic alcohol board practices, etc. But some of this we are doing to ourselves.

There has been article after article about how apps like Grindr are killing gay nightlife because people no longer have to go out to hookup. And this idea has always bothered me because it reduces the raison d’être of nightlife to simply hooking up. But back in the day, in the “Once Upon A Time” of many of my photos, “hooking up” wasn’t the only point of going to a gay club. Rather, it was the gratifying endnote of a sexual public experience, a mise en scène of gay desire that was like nothing else in the known, straight world.

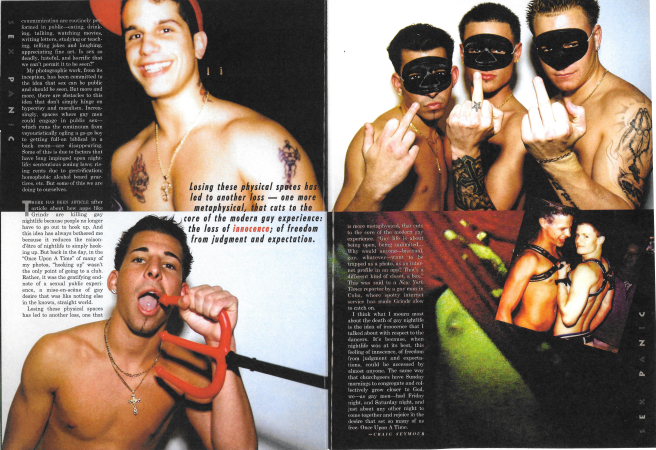

Losing these physical spaces has led to another loss, one that is more metaphysical, that cuts to the core of the modern gay experience. “Gay life is about being open, being unlimited…Why would anyone—bisexual, gay, whatever—want to be trapped as a photo, as an internet profile in an app? That’s a different kind of closet, a box.” This was said to a New York Times reporter by a gay man in Cuba, where spotty internet service has made Grindr slow to catch on.

I think what I mourn most about the death of gay nightlife is the idea of innocence that I talked about with respect to the dancers. It’s because, when nightlife was at its best, this feeling of innocence, of freedom from judgment and expectations could be accessed by almost anyone. The same way that churchgoers have Sunday mornings to congregate and collectively grow closer to God, we—as gay men—had Friday night, and Saturday night, and just about any other night to come together and rejoice in the desire that set so many of us free. Once Upon A Time.

Advertisements Share this:

![still life [rec] copy-sc](/ai/070/892/70892.jpg)