From 2011 Hong Kong conference volume.

I go to some lengths to show how Daoist ritual and religious practice are important topics in the local cultures of north as well as south China (for a succinct encapsulation of the chasm, see here!). But every time I feel I’m establishing some kind of parity for the north (heartland of ancient Chinese culture!), yet more research materializes to remind us just how amazing local ritual traditions are in the south—in terms of both the range and complexity of rituals performed, and in the sheer volume of artefacts preserved there.

As I commented in Appendix 1 of my book Daoist priests of the Li family (where you can find further references),

With the noble exception of studies by Chinese music scholars from the 1930s, fieldwork on local Daoist ritual began in earnest in the 1960s with Kristofer Schipper’s groundbreaking studies in Taiwan. As mainland China began opening up in the 1980s, such work was able to expand first into Fujian and then further afield in south China—Jiangxi, Guangdong, Sichuan, Hunan, Zhejiang, and so on. Major projects (largely in Chinese), led by the indefatigable holy trinity of C.K. Wang, John Lagerwey, and latterly Lü Pengzhi, recruited local cultural workers who went on to develop considerable familiarity with the ritual specialists who were their subjects.

- Wang, C.K. [Wang Ch’iu-kuei 王秋貴] ed., Minsu quyi congshu 民俗曲藝叢書. Taipei: Shi Ho-cheng Folk Culture Foundation, 86 vols (building on an extensive series of articles in the journal Minsu quyi).

See also “The collecting and editing of Taoist ritual texts.” Chinoperl Papers 23 (2000), pp.1–32, and Studies in Chinese ritual, theatre and folklore series: abstracts of the first sixty volumes (1997). - Wang, C.K. ed., Zhongguo chuantong keyiben huibian 中國傳統科儀本彙編 (Taipei: Xinwenfeng), 17 vols.

For useful reviews in English of the early projects, see

- Daniel L. Overmyer, ed., with the assistance of Shin-Yi Chao, Ethnography in China today: a critical assessment of achievements and results. Taipei: Yuan-Liou Publishing Company (2002),

and for a fine overview of such work within the wider context of Daoist studies,

- Vincent Goossaert, “L’histoire moderne du taoïsme: État des lieux et perspectives.” Études chinoises XXXII-2 (2013), pp.7–40.

These vast series continue to yield further discoveries. The latest project, from Xinwenfeng in Taiwan (long an industrious publisher of major works on Daoism) is initially (!) planned to comprise fifteen lengthy monographs:

- John Lagerwey 勞格文 and Lü Pengzhi 呂鵬志, eds., Daojiao yishi congshu 道教儀式叢書.

The southern bias of Daoist studies has a long ancestry: from very early in Chinese history, southern Daoists have dominated the picture. The ritual vocabulary that I provide in my writings on north China is partly an attempt to rebalance a picture largely conditioned by southern Daoism (see also my In search of the folk Daoists, pp. 15–21, 211–213). As I note there,

It is rather as if our knowledge of Christianity in the whole of Europe were based almost entirely on Sicily and Puglia, with the odd footnote on the Vatican and Westminster Abbey. We may like what we find in those places, perhaps considering it more exalted, mystical, and ancient—but that is another issue.

Still, the material here is overwhelming. So far three volumes (each consisting of around 1,500 pages!) have been published in this new series, on local Daoist altars in Jiangxi, Hunan, and Fujian respectively:

- Dai Lihui 戴禮輝 and Lan Songyan 藍松炎, Jiangxi sheng Tonggu xian Qiping zhen Xianyingtan daojiao keyi 江西省銅鼓縣棋坪鎮顯應雷壇道教科儀

- Lü Yongsheng 呂永昇and Li Xinwu 李新吾, Shidao heyi: Xiangzhong Meishan Yangyuan Zhangtande keyi yu chuancheng 師道合一:湘中梅山楊源張壇的科儀與傳承 (for Hunan Daoism, see my overview here)

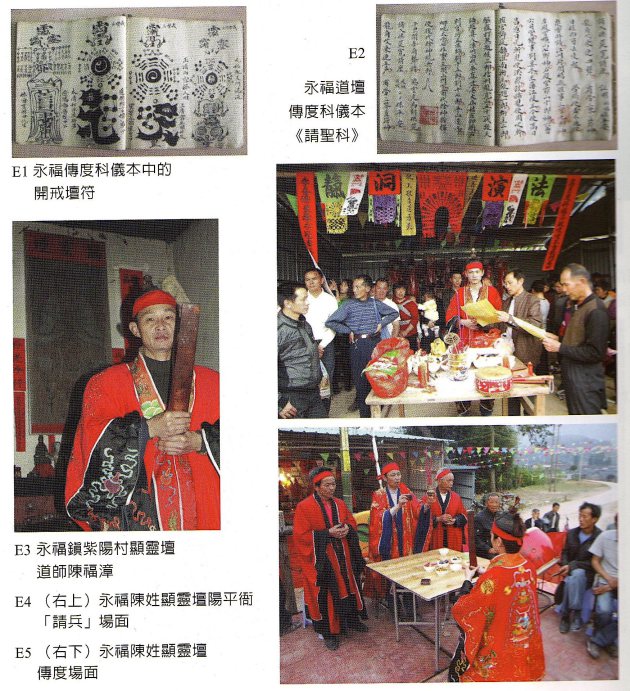

- Ye Mingsheng 葉明生, Minxinan Yongfu Lüshanjiao chuandu yishi yanjiu 閩西南永福閭山教傳度儀式研究

Ye Mingsheng is one of the most distinguished collaborators of the project, having worked for decades on Lüshan household Daoists of Fujian. This new publication focuses on the ordination rituals in Yongfu in the southwest of the province. As John Lagerwey writes in his Abstract:

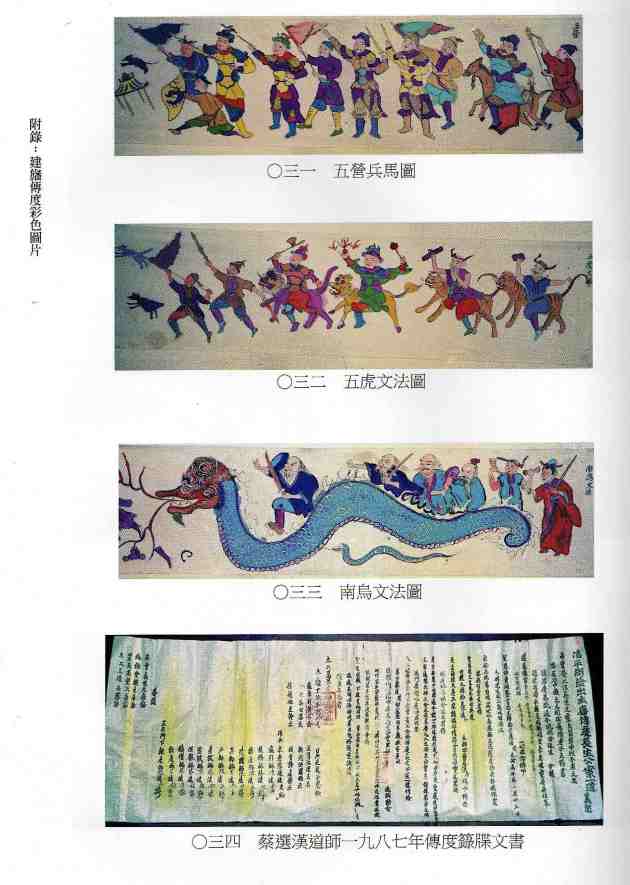

The present book begins with an investigation of the histories of the Daoist altars of four lineages […] in Yongfu. It systematically examines the origins of the local Lüshan school, the structures of their altars, and their rituals, manuscripts, talismans, and registers. It also describes in detail two actual Flag-Raising Transmissions in the years 1999 and 2011, discussing all aspects of the transmission ritual from a variety of disciplinary angles so as to provide students of religion with as complete an understanding as possible.

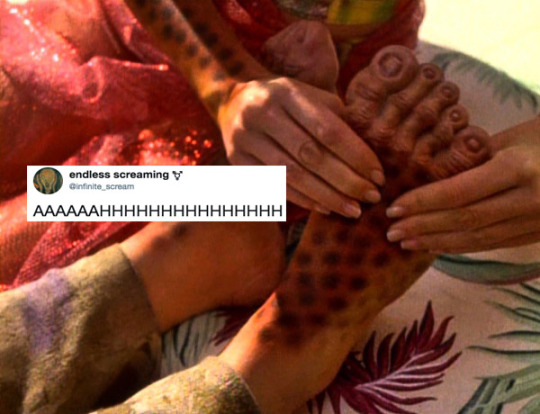

Volume 2 provides a wealth of ritual texts. Among the many photos is a substantial section in colour, including beautiful god paintings.

Still, even photos of ritual practice remain silent and immobile. Given that ritual is noisy and vibrant, part of “red-hot” social performance, the whole project seems to cry out to be accompanied by films. Since the scholars working on these projects have rich archives of fieldwork videos, how very valuable it would be to accompany each topic with an edited film of, say, two or three hours, with voiceovers and/or captions.

Still, even photos of ritual practice remain silent and immobile. Given that ritual is noisy and vibrant, part of “red-hot” social performance, the whole project seems to cry out to be accompanied by films. Since the scholars working on these projects have rich archives of fieldwork videos, how very valuable it would be to accompany each topic with an edited film of, say, two or three hours, with voiceovers and/or captions.

As I observed here, all these series (like the “music-genre” system of Yuan Jingfang), while documenting particular rituals in detail, focus on the salvage of texts—at the expense of ethnographic study, performance practice, and social change. Now, faced by such a wealth of precious manuscripts it’s no simple task to incorporate the topic into wider discourses on a society in constant change. But many students of religion, for whom social and political changes over the past century are a major topic, may find that “variety of disciplinary angles” elusive. They may miss even succinct discussion of how local ritual traditions have been affected by such mundane issues as migration, successive political campaigns, and changing economic circumstances—all the more since the subject of this new volume is transmission, utilizing field material from 1999 and 2011, through yet another period of change. [1]

Still, none of this detracts from the value of the project. This vast body of work on local ritual in south China continues to form the vanguard of Daoist ritual studies—essential material on Chinese religion.

[1] For basic biographical accounts of the Yongfu Daoists, see pp.79–103.

New post on stephenjones.blog!