The more I examined the architecture of my life, the more I realized how fraudulent were its foundations.

This is a book that wasn’t even on my radar until fairly late on in the year, when I noticed just how many of my Goodreads friends had read it and rated it – almost without fail – 5 stars. I knew John Boyne’s name only through the movie version of his Holocaust-set novel for younger readers, The Boy in the Striped Pajamas, and didn’t think I’d be interested in his work. But the fact that The Heart’s Invisible Furies was written in homage to John Irving (Boyne’s dedicatee) piqued my interest, and I’m so glad I gave it a try. It distills all the best of Irving’s tendencies while eschewing some of his more off-putting ones. Of the Irving novels I’ve read, this is most like The World According to Garp and In One Person, with which it shares, respectively, a strong mother–son relationship and a fairly explicit sexual theme.

A wonderful seam of humor tempers the awfulness of much of what befalls Cyril Avery, starting with his indifferent adoptive parents, Charles and Maude. Charles is a wealthy banker and incorrigible philanderer occasionally imprisoned for tax evasion, while Maude is a chain-smoking author whose novels, to her great disgust, are earning her a taste of celebrity. Both are cold and preoccupied, always quick to remind Cyril that since he’s adopted he’s “not a real Avery”. The first bright spot in Cyril’s life comes when, at age seven, he meets Julian Woodbead, the son of his father’s lawyer. They become lifelong friends, though Cyril’s feelings are complicated by an unrequited crush. Julian is as ardent a heterosexual as Cyril is a homosexual, and sex drives them apart in unexpected and ironic ways in the years to come.

A wonderful seam of humor tempers the awfulness of much of what befalls Cyril Avery, starting with his indifferent adoptive parents, Charles and Maude. Charles is a wealthy banker and incorrigible philanderer occasionally imprisoned for tax evasion, while Maude is a chain-smoking author whose novels, to her great disgust, are earning her a taste of celebrity. Both are cold and preoccupied, always quick to remind Cyril that since he’s adopted he’s “not a real Avery”. The first bright spot in Cyril’s life comes when, at age seven, he meets Julian Woodbead, the son of his father’s lawyer. They become lifelong friends, though Cyril’s feelings are complicated by an unrequited crush. Julian is as ardent a heterosexual as Cyril is a homosexual, and sex drives them apart in unexpected and ironic ways in the years to come.

For Cyril, born in Dublin in 1945, homosexuality seems a terrible curse. It was illegal in Ireland until 1993, so assignations had to be kept top-secret to avoid police persecution and general prejudice. Only when he leaves for Amsterdam and the USA is Cyril able to live the life he wants. The structure of the novel works very well: Boyne checks in on Cyril every seven years, starting with the year of his birth and ending in the year of his death. In every chapter we quickly adjust to a new time period, deftly and subtly marked out by a few details, and catch up on Cyril’s life. Sometimes we don’t see the most climactic moments; instead, we see what happened just before and then Cyril remembers the aftermath for us years later. It’s an effective tour through much of the twentieth century and beyond, punctuated by the AIDS crisis and focusing on the status of homosexuals in Ireland – in 2015 same-sex marriage was legalized, which would have seemed unimaginable a few short decades before.

Boyne also sustains a dramatic irony that kept me reading eagerly: the book opens with the story Cyril’s birth mother told him of her predicament in 1945, and in later chapters Cyril keeps running into this wonderfully indomitable woman in Dublin – but neither of them realizes how intimately they’re connected. Thanks to the first chapter we know they eventually meet and all will be revealed, but exactly when and how is a delicious mystery.

Along with Irving, Dickens must have been a major influence on Boyne. I spotted traces of David Copperfield and Great Expectations in minor characters’ quirks as well as in Cyril’s orphan status, excessive admiration of a romantic interest, and frequent maddening failures to do the right thing. But there are several other recent novels – all doorstoppers – that are remarkably similar in their central themes and questions. In Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch, Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life and Nathan Hill’s The Nix we also have absent or estranged mothers; friends, lovers and adoptive family who help cut through a life of sadness and pain; and the struggle against a fate that seems to force one to live a lie. Given a span of 500 pages or more, it’s easy to become thoroughly engrossed in the life of a flawed character.

The Heart’s Invisible Furies – a phrase Hannah Arendt used to describe the way W.H. Auden wore his experiences on his face – is an alternately heartbreaking and heartening portrait of a life lived in defiance of intolerance and tragedy. A very Irish sense of humor runs all through the dialogue and especially Maude’s stubborn objection to fame. I loved Boyne’s little in-jokes about the writer’s life (“It’s a hideous profession. Entered into by narcissists who think their pathetic little imaginations will be of interest to people they’ve never met”) and thanks to my recent travels I was able to picture a lot of the Dublin and Amsterdam settings. Although it’s been well reviewed on both sides of the Atlantic, I’m baffled that this novel doesn’t have the high profile it deserves. I am especially grateful to Sarah of Sarah’s Book Shelves for naming this her book of the year: knowing her discriminating tastes, I could tell I’d be in for something special. Look out for it on my Best Fiction of 2017 list tomorrow.

My rating:

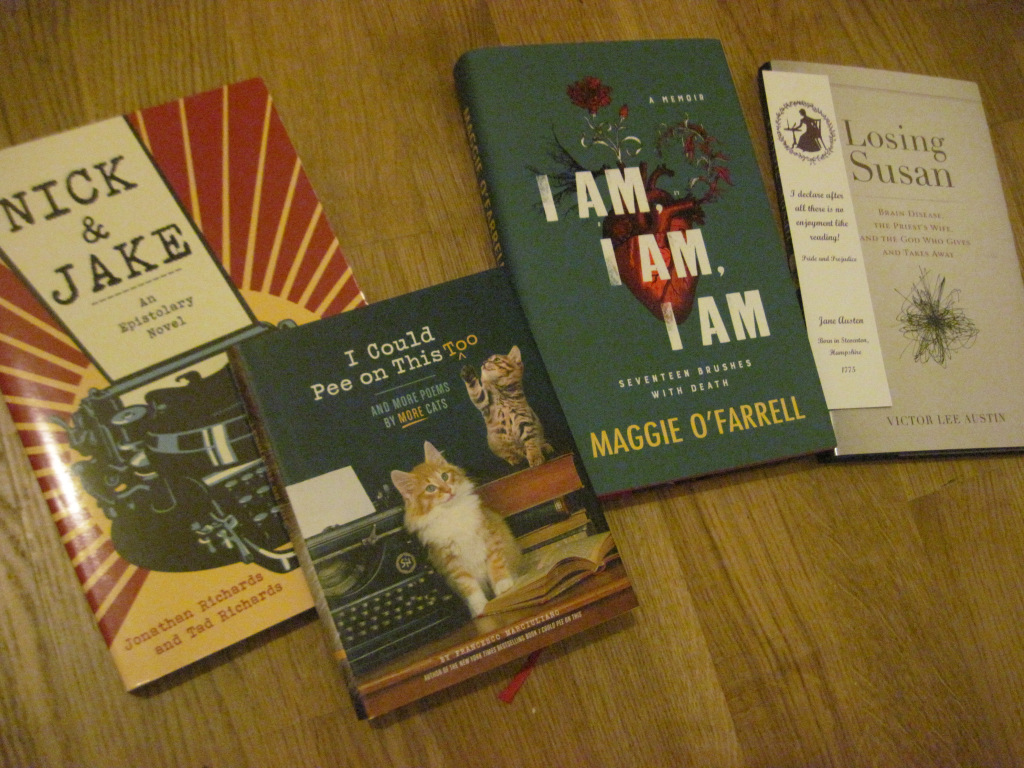

I got just four books for Christmas this year, but they’re all ones I’m very excited to read. I looked back at last year’s Christmas book haul photo and am impressed that I’ve actually read seven out of eight of them now – and the eighth is a cocktail cookbook one wouldn’t read all the way through anyway. All too often I let books sit around for years unread, but I will try to keep up this trend of reading books fairly soon after they enter my collection.

- Doorstopper of the Month

- Fiction Reviews

![BEAUTY by [Liney, Peter]](/ai/037/271/37271.jpg)