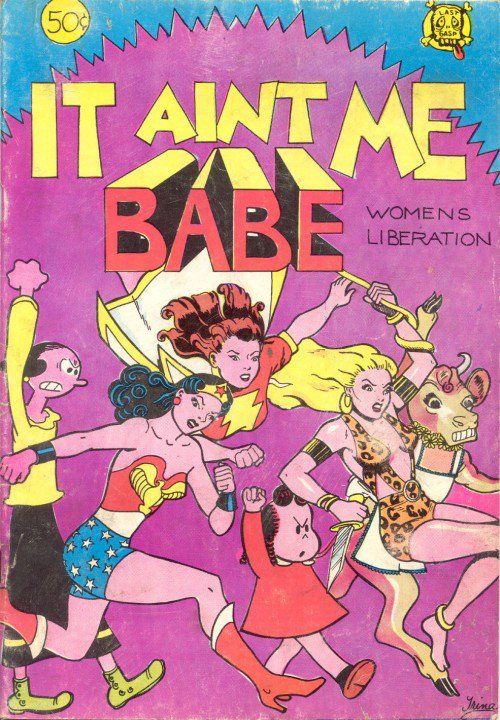

Fantasyland: How America Went Haywire: A 500-Year History is a lengthy, sprawling look at U.S. history with the aim of explaining how this country reached the point of electing Donald Trump. Along the way, the author tries to fit everything under the sun that can be, or has been, seen, felt, or experienced in America under the rubric “fantasy-industrial complex,” with mixed results. In the end, the book is enlightening on a few topics, boring and repetitious on most topics, and deeply confusing on its main topic, which happens to be religion. According to Kurt Andersen, religion is, in fact, America’s original sin.

Fantasyland: How America Went Haywire: A 500-Year History is a lengthy, sprawling look at U.S. history with the aim of explaining how this country reached the point of electing Donald Trump. Along the way, the author tries to fit everything under the sun that can be, or has been, seen, felt, or experienced in America under the rubric “fantasy-industrial complex,” with mixed results. In the end, the book is enlightening on a few topics, boring and repetitious on most topics, and deeply confusing on its main topic, which happens to be religion. According to Kurt Andersen, religion is, in fact, America’s original sin.

Although the title gives nothing away, the author admits some 300 pages into the book that American faith is of primary importance in his argument. “The big, undeniable piece of American exceptionalism that helped launch this inquiry,” he explains, “is our religiosity.” Throughout the book he tries very hard to draw a straight line from the Puritans to Trump – a great irony, considering the man’s complete lack of religious sensibility. To be fair, Andersen admits as much. And this book, after all, is no academic study, carefully arguing cause/effect, or even tracing very precise lines from one idea to the next, as the lack of serious documentation indicates.

“According to Kurt Andersen, religion is, in fact, America’s original sin.”Rather, the book is more like a tone poem, riffing on the dark theme of fantasy and the treacherous undercurrents of make-believe that Andersen insists are peculiar to America alone. “America is the freak,” he insists, and quotes statistics that align us with third-world countries when it comes to religious belief. So he has written this book, he explains, to “register the connections between our religion and the rest of our giddy, uncertain grip on reality.” Mindful that our Puritan ancestors transported their “supernatural fantasies to the new world,” he worries that “we have rushed headlong back toward magic and miracles” in the way not only of Puritans, but of Shakers, Quakers, and Salem witch trials.

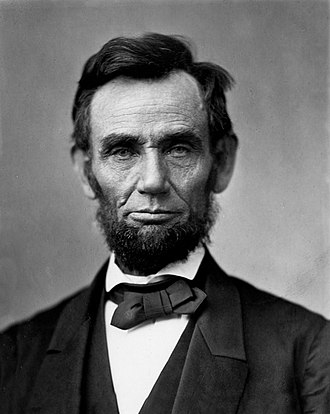

Kurt Andersen

Kurt Andersen

“American Christianities,” he argues, are “special mixtures of superstition, selfishness, and a refusal to believe in the random.” He recalls feeling “pleased” when he was in the sixth grade, running across the Time magazine cover that posed the question “Is God dead?” At last, he thought, “upper-middle Americanism was ratifying what the smart people knew but were too polite to say in public . . . religion had reached its sell-by date.” Thus simple belief in God is often the subject of Andersen’s scorn, though he reserves special scorn for charismatic religions. He ignores their artistic and cultural significance, for instance, and barely mentions African-American influence, only twice describing early Pentecostal church-goers – shockingly – as “quarantined . . . in hollers and slums.”

In the meantime, religion isn’t the only American fantasy that’s subject to his withering scorn. Included in that list are television, movies, theme parks, Dungeons and Dragons, motorcycle gangs, shopping malls, suburbia, state lotteries, the pill, breast implants, sports, rap music, SUVs, pornography, and chocolate chip cookie dough ice cream. These pernicious distractions were preceded, historically, by others: occultism, quackery, Christian scientists, gold rushes, conspiracy theories, the Civil War, Henry David Thoreau, advertising, circuses, world fairs, and the John Birch Society – to name only a few. Suffice it to say that Kurt Andersen leaves no stone unturned if he can help it and, unfortunately, turns several of them over more than once. Any American experience or artifact you can think of, in short, he can probably manage to fit somewhere beneath the umbrella of his idea of the fantasy-industrial complex — and to go on and on about it.

“The book is like a tone poem, riffing on the dark theme of fantasy and the treacherous undercurrents of make-believe that Andersen insists are peculiar to America. “The reader can’t help but wonder if Andersen’s sweeping analysis is too contrived, too easy by half. Does he really have his finger on the pulse of American culture, or is all his cleverly packaged contempt just a bit too shallow? A brief look at his analyses of a few Western icons gives us a clue about the man’s true level of skill at culture-whispering. Abraham Lincoln, Henry David Thoreau, Sigmund Freud, and J.R.R. Tolkien, all are mentioned in his Fantasyland.

J.R.R. Tolkien

J.R.R. Tolkien

Andersen claims that not only did both sides in the Civil War cling to the idea that God was on their side, but that Abe Lincoln did the same. Amazingly, he quotes Lincoln’s famous second inaugural address (“with malice toward none, with charity for all”) as proof. In this speech – historically considered a bastion of evenhandedness and generosity – the author professes to find 200 words that support his idea that Lincoln claimed divine retribution for the North, although he doesn’t bother to parse the passage.

So let me do the parsing – here’s an accurate paraphrase of the 200 words that immediately precede the “malice” passage: “If God wills that the war continue so that both sides be punished for the sin of slavery, so be it.” I defy the author to parse the passage in any other way, and remain dumbfounded at either his failure to understand the particulars and the context of this brief passage, or his deliberate distortion of the text.

“The reader can’t help but wonder if Andersen’s sweeping analysis is too contrived, too easy by half. Does he really have his finger on the pulse of American culture?”The author also harbors an open, withering contempt for Henry David Thoreau – his one-time hero – because Thoreau, he claims, “invented a certain kind of entitled, upper-middle-class extended adolescence,” seeking to live “a life in harmony with nature as long as it’s not too uncomfortable or inconvenient.” I suggest that the author take a good look at a couple of things: first, the survey of Walden Pond currently housed in the Concord Free Public Library, courtesy of the labors of Henry David Thoreau.

Thoreau was a professional surveyor who, after waiting for the dead of winter during his two-year stay at Walden, walked out onto the icy pond carrying plumb line, axe, chain, and tripod, to expertly plumb the water’s depths. He left a record of his findings for his community and for the thrilled perusal of future generations, who will, of course, always love him. Just asking: Can Mr. Andersen claim any physical task of his own that compares to the beauty and toil of this act, or any book that comes close to the lasting quality of Walden?

Thoreau was a professional surveyor who, after waiting for the dead of winter during his two-year stay at Walden, walked out onto the icy pond carrying plumb line, axe, chain, and tripod, to expertly plumb the water’s depths. He left a record of his findings for his community and for the thrilled perusal of future generations, who will, of course, always love him. Just asking: Can Mr. Andersen claim any physical task of his own that compares to the beauty and toil of this act, or any book that comes close to the lasting quality of Walden?

Second, Andersen should consider reading Laura Dassow Walls’ acclaimed biography of Thoreau, which was reviewed on this blog Aug. 15, and which exhibits a brilliant, deeply sympathetic view of the man’s life. While he’s at it, the author might also want to check out this blog’s review of Freud, The Making of an Illusion by Frederick Crews – a book that hammers the last nail in the coffin of a man whose stature has steadily diminished over the last fifty years, and whom few authors are willing to cite as an authority on anything these days, much less in the oblivious way that Andersen does repeatedly in Fantasyland.

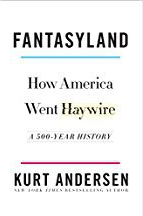

Finally, it absolutely defies belief that the author quotes J.R.R. Tolkien’s 1939 essay “On Fairy Stories” in support of his idea that American fantasy is toxic. Tolkien, first, was not only a creator of fantasy, but an ardent defender of its usefulness and value. Second, and even more important, he was also a lover of the tale of the life of Christ, and believed that the Christian story was not just fable, but fact: “This story is supreme, and it is true,” he wrote in this essay. “Art has been verified. . . . Legend and history have met and fused.”

Finally, it absolutely defies belief that the author quotes J.R.R. Tolkien’s 1939 essay “On Fairy Stories” in support of his idea that American fantasy is toxic. Tolkien, first, was not only a creator of fantasy, but an ardent defender of its usefulness and value. Second, and even more important, he was also a lover of the tale of the life of Christ, and believed that the Christian story was not just fable, but fact: “This story is supreme, and it is true,” he wrote in this essay. “Art has been verified. . . . Legend and history have met and fused.”

Yet Andersen, who most surprisingly confesses near the end of his book to agree with much of what Tolkien writes, still uses this essay to support his idea that fantasy is largely toxic: “Fantasy can, of course, be carried to excess,” Tolkien writes. “It can be put to evil uses. It may even delude the minds out of which it came.” Once again, however, context is everything. Tolkien immediately follows with this passage, which Andersen conveniently ignores: “But of what human thing in this fallen world is that not true? . . . Fantasy remains a human right: we make in our measure and in our derivative mode, because we are made: and not only made, but made in the image and likeness of a Maker.”

A writer who disingenuously quotes without regard to context, who recklessly misinterprets others’ words, who exudes scorn and derision for things and people of high value to a nation, cannot possibly be capable of seeing the big picture. I found this book dismaying and, worse, boring. I can’t recommend it.

Ω

Share this: