Dark Angel Episode 1: Pilot

Written by James Cameron and Charle H Eglee

Directed by David Nutter

The end of the world brings with it a kind of ecstasy. It is a release from care. It is the dropping of the other shoe. This is why we love stories of the end times, we love to imagine how our lives would be better if they were reduced down to our primal needs; the struggle for survival. In most post-apocalyptic movies this release is shown in an orgy of violence, a libertarian fantasy where stockpiling guns and distrusting your neighbours are valid life choices. It is even better if it is zombies because then you get to shoot the people who you think want to eat you.

In The Hunger Games Katniss Everdeen (played in the movie by Jenifer Lawrence) dreams of living alone in the wilderness but is instead forced to take part in a child sacrifice ritual where her fears and anxieties (caring for her younger sister, struggling for food, having to be a leader) are literalised. The pressures that were killing her in the abstract are suddenly survivable when they are made concrete. The same could be said for The World’s End a genre parody of alien invasion movies where the suicidal Gary King (Simon Pegg), who is unable to function in normal society, finds the peace he needs when aliens start replacing people with robots. Suddenly that internal feeling that everyone else has access to a programme you never got aligns with reality – and, again, you get to shoot people.

This is the post-apocalyptic fantasy; our lives will no longer be mediated by rules, by society, by things we can’t see. The daily grind of work and chores that help us feed our family and keep a roof over our head will suddenly stop and we will instead spend our days, working, doing chores, feeding our families and keeping a roof over our head but the difference will be that it is us who are doing it. We will hunt the food and build the cabin, we will be happy in our work, our families will appreciate us. The popularity of these stories implies a belief in what therapists call an external locus of control. For some people aliens, or fascists or zombies are welcome because their presence justifies the stress and anxiety they already feel.

One common trope is exemplified by Ray Ferrier (Tom Cruise) in War of the Worlds. Before the Martians attack earth he is a struggling working class dad living in a depressed urban neighbourhood unable to connect with his kids and divorced from the woman he loves. When the attack happens he is able to prove himself as a strong male hero worthy of his kids love and is welcomed back into his wife’s suburban McMansion (even if this makes no sense). There are numerous others, Jeff Goldblum in Independence Day, John Cusack in 2012, though if I start listing movies that show how the end of the world fixes the male hero’s dysfunctional relationships I’ll be here all day (even if I restrict myself to Roland Emmerich movies).

The dark side of the fantasy is that it depends on the hero surviving and on a lot of other people dying. The unspoken wish of the survivalist is for a catastrophe or a holocaust to happen (just not to them). They want something bad enough that it gives their life meaning but not so bad it kills them and the people they love. It’s not just a dark side the apocalypse genre has a smug anti-human streak. The high kill count is seen as a positive and usually justified on moral grounds; the people who get turned into mindless zombies are usually mindless consumers, the people killed by environmental collapse were polluters. An important scene in most movies of this sort involves the hero having Casandra like visions of the coming conflagration that are dismissed by the folks around them, think Dennis Quaid in The Day After Tomorrow, the good Christians in Left Behind, Will Smith in I, Robot, the role of these predictions is to justify the suffering – if you had listened to me you would have changed your wicked ways.

In Dark Angel, a show whose two seasons straddle the anxiety ridden turn of the millennium, this desire for the end is put under the microscope. The apocalypse occurred in 2009 in the form of the Pulse; an EMP set off by some “terrorist bozos.” The Pulse destroyed the electricity grid, internet, banks and records, and was used as an opportunity by the government to clamp down on rights and freedoms. Logan (Michael Weatherly), a hacker and free speech activist who also happens to live in a fancy penthouse surrounded by art and luxury goods, provides the perspective of someone who was well off before the Pulse. In his view the people blinked, they invited in their new overlords. “Overnight, the government, the police, everything intended to protect the people had been turned against them.” Logan is trying to reach out to the people who chose fascism and show them how even if they think they are better off they are deluding themselves the popularity of the post-apocalyptic narrative suggests he might find it difficult.

Max (Jessica Alba) comes from a different class, race, gender and educational perspective to Logan. At the time of the Pulse she was a child on the run from a para-governmental organisation who had created her in a lab. She already had to struggle to survive and in many ways the destruction of records made it easier for her and others on the fringes to get by. From her perspective what actually disappeared in the pulse was the illusion of stability and fairness. The old days Logan wants to return to were a time “when people spent obscene amounts of money decorating the house to match the cat.” There is still wealth disparity in the new world, there are still poor people, like Max’s army vet neighbour Theo dying from lack of healthcare, there is police brutality, corruption and all the bad stuff that existed before now however it is exposed. Wanting to go back is as bad as choosing the easy solution of men with guns providing order. Max represents a class of people who probably wouldn’t go see the latest Roland Emmerich or watch The Walking Dead on TV because they don’t need the deaths of millions to justify their irrational feelings of persecution or the threat of ravening hordes to justify their stockpiling of wealth, land and guns.

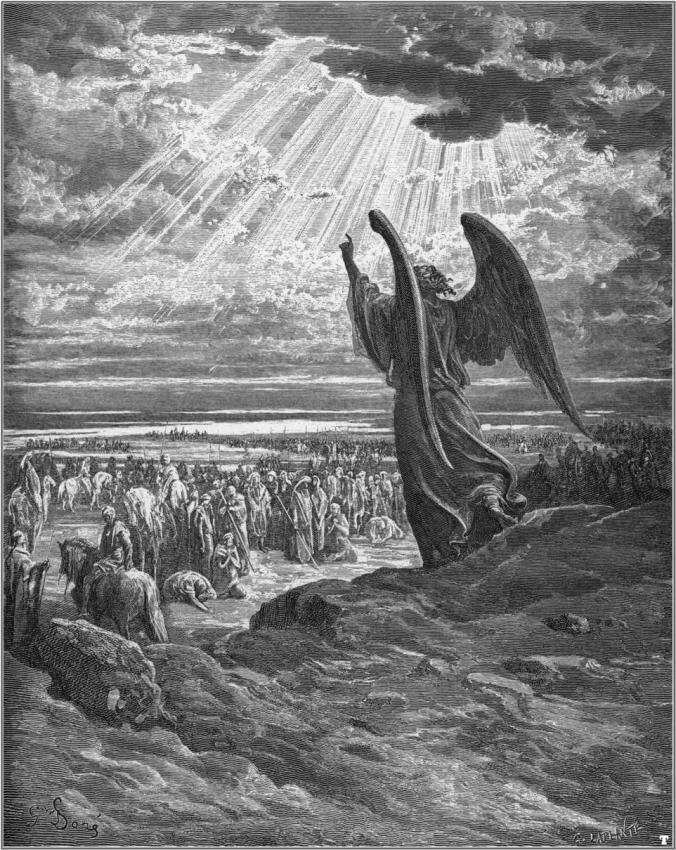

Apocalypse doesn’t mean the end of the world taken literally it means a revelation of the truth. It is a spiritual exercise, a meditation on death and destruction, a way to discard what holds you down and reaffirm what is important to you. For religious communities end times prophecies work to reassure and comfort the afflicted and persecuted. State religions rarely emphasise this eschatology which tends to be anti-statist but it increases in importance the further one gets from the centre. In mature religious communities the apocalypse, whether it is Ragnarok or the Rapture, is understood to work in tandem with the idea of salvation or rebirth. It is a stage in historical or personal development that must be withstood and moved through.

Immature religions and cults can often get caught up in the fire and brimstone without moving beyond. This is also true of the worst of the survivalist/zombie/killer alien invasion stories which revel in the violent chaotic, the liberation from the material, without moving forward into the reconstruction phase. Even mainstream movies like War of The Worlds usually end at the moment of reunion and ignore the fifty years to come after that. The Walking Dead spin-off Fear The Walking Dead is a prequel returning to the initial period of destruction and avoiding the hard (but much more interesting) questions that would come in a sequel set ten, fifty, a hundred years after the zombie outbreak. We cannot stay in the ecstatic moment of revelation or it will transmute into nihilism. To keep it going we will need to escalate the violence and the killing like so many Resident Evils (or burn down our compound while taking fire from the ATF) until there is nothing left.

Dark Angel isn’t set in 2009 it takes place in 2019. By making the ten year leap over the period of violence that is only occasionally alluded to (but which definitely followed the Pulse) it becomes a show about building a new community. It is about the freaks and the people who slipped through the cracks finding each other. After the apocalypse, after the survivalists and the power- fantasists have wandered across the wasteland firing their guns and burning their fuel there needs to be a new way forward. Max needs to be a different kind of hero who will make friends and care for people. Even her name makes this point. The Mad Max franchise is the most iconic representation of the society breakdown fantasy. By calling their lead character Max the show’s creators building a strong contrast. Our Max has a Kawasaki Ninja and not a V8 Interceptor but unlike Max Rockatansky she is happy to restrict her driving to the late night hours when she is unlikely to hurt anyone.

In the pilot Max is not yet the hero she will become but she is getting there. She is a thief (sorry, a cat burglar) but she steals to pay a private detective who is helping her find her missing siblings. She has a job to pay her rent, a housemate, work friends, a jerk of a boss. Max is already unique in genre television for holding down a day job, especially a minimum wage service industry job, and this is a deliberate early rejection of the usual tropes of post-apocalyptic fantasy. She has training and the superpowers; there is literally nothing but her own will power stopping her from being a cool existentialist samurai wandering the Badlands but Max chooses to embrace what most end of the world stories offer to free us from; the daily grind. “Hope is for losers,” Max says in her opening narration but she only half believes it. Instead she seeks the stability and community she never had as a child and in making herself into a normal human, in getting involved and investing in the people around her she makes herself into someone capable of hope – a loser.

Share this: