Grief loves the hollow, all it wants is to hear its own echo. Be careful.

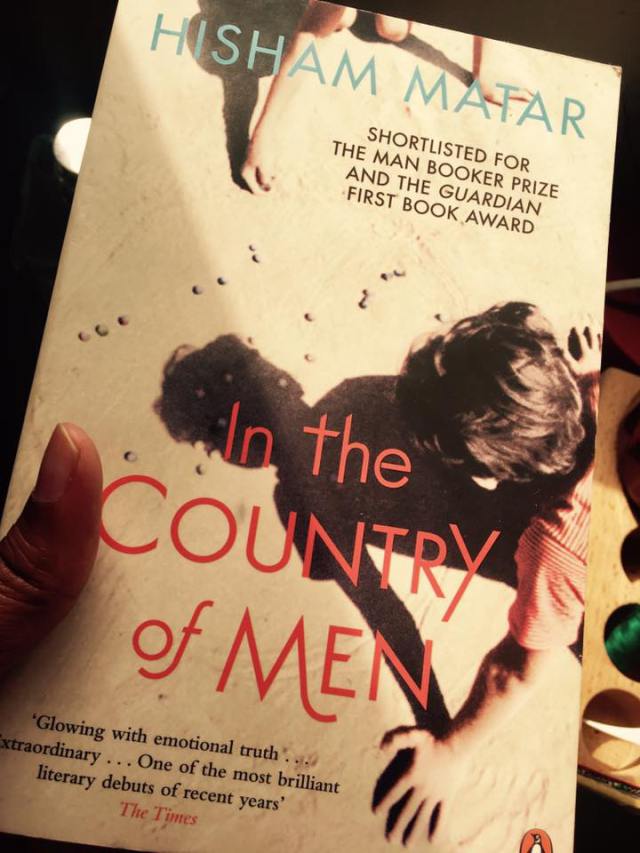

Many times while reading Hisham Matar’s ‘In the Country of Men’, I asked myself if this book would have resonated so much with me had I not been living here, in the UAE. If I had not had, among my friends, people who hail from other Middle East nations. If we had not shared stories with each other over tea and croissants. Or reminisced longingly about our home countries while maneuvering the rush hour traffic…

The answer is, probably not. Because some stories tend to remain once removed until they enter your immediate orbit. Until the ambiguous ‘they’ becomes a Maha, Sameh or Yasmin. Until you see at close quarters the shadow of displacement and hopeless longing at the edges of their brown, sun-lit eyes. Then they begin to find their echo in you.

Once, early on in my brief stint with a corporate house as its content provider, I was introduced to someone who had just come back from Syria after the funeral of his sister. She had been arrested some weeks ago for taking part in protests. In the same office, a young girl, only slightly older than my son, went to her country on vacation and was held there under house arrest. In the idealism of her youth, she had posted some images of protests on social media. It took months of intervention for her to be allowed out of her country.

In the Country of Men reminded me of all these stories. And others I have heard and read over the past twelve years in the Middle East.

Set in Tripoli, Libya, during Qaddafi’s regime, the narrative unfolds as a series of events seen through the eyes of nine-year-old Suleiman. Slooma, as he is fondly addressed by the people close to him, is a not-very-silent witness to personal and political realities he is unable to fully grasp. His beautiful yet ‘ill’ mother is an enigma; so is his businessman father who suddenly goes away without informing him. Then there are others – friends, neighbours, and acquaintances – whose lives are inextricably tied to his own: Moosa, Nasser and several others, including his friend and next door neighbour Kareem and his father Ustath Rashid.

Suleiman is puzzled and deeply hurt by the events that unfold, and he reacts to them in ways that only a child is capable of. In the end, he too bears the brunt of an uprising gone wrong in the world of adults.

In the Country of Men is also a story of love – the love of a nine-year-old son for his mother. She who condemns Sheherzadie of One Thousand and One Nights for choosing the life of a slave over death. Suleiman’s love for his mother is complex, often inexplicable even to himself. He longs to protect her from her own past, from all the men who seem to run her life. Yet there are times when he is filled with anger and hatred towards this self-absorbed woman with secrets he can’t bear to be privy to.

If love starts somewhere, if it is a hidden force that is brought out by a person, like light off a mirror, for me that person was her. There was anger, there was pity, even the dark, warm embrace of hate, but always the joy that surrounds the beginning of love.

In the Country of Men certainly has its moments. Poignant ones. Some as beautiful as the Mediterranean sea and sky they evoke. And there are words that linger even after you close the book and put it away.

I suffer an absence, an ever-present absence, like an orphan not entirely certain of what he has missed or gained through his unchosen loss. (…) How readily and thinly we procure these fictional selves, deceiving the world and what we might have become if we hadn’t got in the way, if only we had waited to see what might have become of us.

So it goes, Matar’s narrative, which effectively conveys Suleiman’s love, loneliness, bewilderment and misplaced anger to the reader, while highlighting the pervading sense of the fear and anxiety that stems from Libya’s political climate of the time. The unease that Suleiman feels is also the reader’s.

I have to admit though that I was left feeling a little dissatisfied, especially towards the end, when the story suddenly seems to fragment, dissipate. There are paragraphs that felt disjointed and rushed, pages I sought more from. When I turned the last page and closed the book, I couldn’t help but feel that the narrative stopped just short of achieving something. Poetry, perhaps. Or something equally vague.

Or perhaps the fault lies in my expectations.

For a while now, I had been reading more about books than books themselves. My desk and bookshelf are full of half-read fiction, non-fiction and poetry. Sometimes I feel as if the summer has a vice-grip on my soul, not allowing me to focus on anything. ‘In the Country of Men’ is, in truth, the first book I have completed in many weeks. And I feel a sense of release – as if a dark spell has been broken. As if the ennui, the listlessness, will soon begin to ebb, like the heat outside. In that sense, I do have a lot to be grateful for. To Hisham Matar’s Man Booker Prize-nominated book.

Advertisements Share this: