I’m an introvert so I spend a great deal of time inside my own head. It’s always noisy in there, with ideas and facts and impulses and emotions pushing up against each other like commuters crossing the tidal flow of a Tube Station, but I hadn’t realised just how much of the noise comes from my job until I moved to part-time working this month.

I’ve been working for almost four decades now. I’m acclimated to the mental noise pollution of work. It reminds me of watching the “Battle Star Galactica” TV series on my computer and finding that using headphones meant that I was constantly aware of the noise of the spacecraft engines in the background. Now, I feel as if the engines have been shut off and my mental ears are adjusting to their absence.

In this growing quiet, I hear the cries of distant poets. These are the folks I had in mind when I wrote “Wave Wet Sand”, the ones who landed early and never really left.

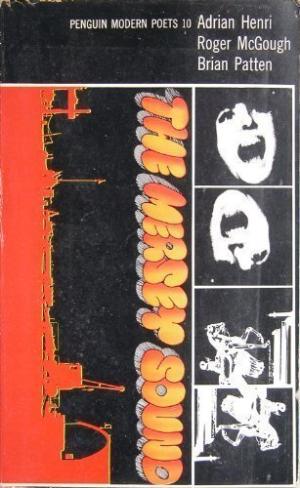

I grew up on Merseyside so naturally, I started with the pop poetry of the Liverpool poets: Adrian Henri, Roger McGough and Brian Patten. My first poetry book, purchased with birthday book tokens was a Penguin Paperback called “The Mersey Sound” where the three of them taught me that poetry wasn’t pious or dull.

I grew up on Merseyside so naturally, I started with the pop poetry of the Liverpool poets: Adrian Henri, Roger McGough and Brian Patten. My first poetry book, purchased with birthday book tokens was a Penguin Paperback called “The Mersey Sound” where the three of them taught me that poetry wasn’t pious or dull.

I was infatuated with Adrian Henri’s “Love Is” which starts:

“Love is feeling cold in the back of vans

Love is a fanclub with only two fans

Love is walking holding paintstained hands

Love is.”

Brian Patten’s “Party Piece” took me beyond my teenage experience, describing a man asking a, perhaps newly met, woman to have sex but the last verse, in particular, sounded true to my Catholic-educated ears:

“So they did,

There among the woodbines and guinness stains,

And later he caught a bus and she a train

And all there was between them then

was rain.”

But the one I liked best then and still relish now that I’m in my sixties was Roger McGough’s “Let Me Die A Young Man’s Death” which starts:

“Let me die a youngman’s death

not a clean and inbetween

the sheets holywater death

not a famous-last-words

peaceful out of breath deathWhen I’m 73

and in constant good tumour

may I be mown down at dawn

by a bright red sports car

on my way home

from an allnight party”

I’m not the all-night party type but I appreciate the boldness of the sentiment.

At the same time, my sister and I used to read Robert Browning’s “My Last Duchess” aloud to each other, savouring the cold chill of being in the presence of an intelligent, educated, pitiless, narcissistic psychopath.

The poem is a monologue by a Duke giving an informed description of a portrait of his last Duchess. The tone at first is civilised but violence swims in circles beneath the surface, showing a fin for the first time when the Duke lets his mask slip and says of his wife now dead wife:

“She had

A heart—how shall I say?—too soon made glad,

Too easily impressed; she liked whate’er

She looked on, and her looks went everywhere.”

Long before I read “Silence Of The Lambs”, Browning’s poetry had shown me the flat dead eyes of a killer.

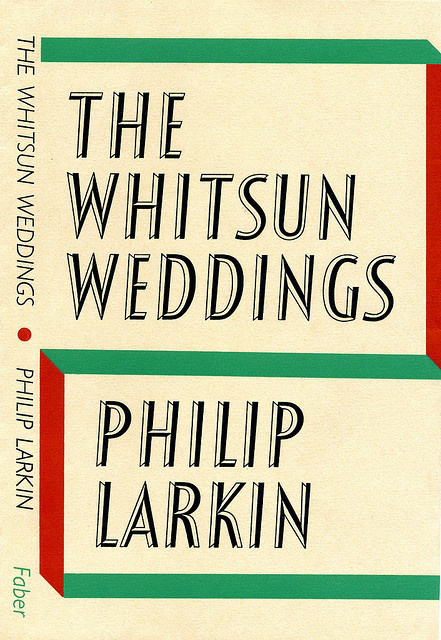

At university, I discovered Philip Larkin whose gift was to capture the grubbiness of despair and the dismal necessity of persisting.

At university, I discovered Philip Larkin whose gift was to capture the grubbiness of despair and the dismal necessity of persisting.

I bought his “Whitsun Weddings” in the slim but stylish Faber and Faber paperback that looked far posher than any Penguin book but contained down to earth wisdom.

I still keep that edition close at hand. Over the years I’ve seen the meaning of the poems shift as my experience gives me new angles to look at them from.

My current favourite is “A Study Of Reading Habits” where growing up means leaving reading-led fantasies of macho manhood behind. The last verse reads:

“Don’t read much now: the dude

Who lets the girl down before

The hero arrives, the chap

Who’s yellow and keeps the store

Seem far too familiar. Get stewed:

Books are a load of crap.”

Larkin taught me that things can always get worse if you think about them for long enough.

Other voices call to me more faintly:

T.S. Eliott whose “The Lovesong of J. Alfred Prufrock” taught me that I didn’t need to be able to decode everything in a poem to savour its atmosphere. How could I not fall in love with:

“I should have been a pair of ragged claws

Scuttling across the floors of silent seas”

Thomas Wyatt who taught me that the order of words can be as powerful as the words themselves with his “They Flee From Me Who Sometimes Did Me Seek” which starts:

“They flee from me that sometime did me seek

With naked foot, stalking in my chamber.

I have seen them gentle, tame, and meek,

That now are wild and do not remember

That sometime they put themselves in danger

To take bread at my hand; and now they range,

Busily seeking with a continual change.”

And Oliver Goldsmith who taught me in his “Elegy On The Death Of A Mad Dog” that poetry could be used as a sword by smiling street corner brawler poets declaiming satirical damnation to passers-by.

Read this aloud. Assail people with it. Let the rhythm and the rhyme do their work. Here are a couple of verses from the middle of the poem that always get a laugh and set up the bite at the end of the poem:

“And in that town a dog was found,

As many dogs there be,

Both mongrel, puppy, whelp, and hound,

And curs of low degree.This dog and man at first were friends;

But when a pique began,

The dog, to gain some private ends,

Went mad, and bit the man.”

But the poet of poets, the one who comes back to my ears in this growing quiet not as a whisper but as a roar is Dylan Thomas who summed up the richness of poetry for me in his “Notes On The Art Of Poetry”

“I could never have dreamt that there were such goings-on

in the world between the covers of books,

such sandstorms and ice blasts of words,,,

such staggering peace, such enormous laughter,

such and so many blinding bright lights,, ,

splashing all over the pages

in a million bits and pieces

all of which were words, words, words,

and each of which were alive forever

in its own delight and glory and oddity and light.”

I shall nurture the quiet that has let me hear poems again by finding new voices to fill my head.

Let me know if you have any suggestions.

Advertisements Rate this:Share this:

- Share