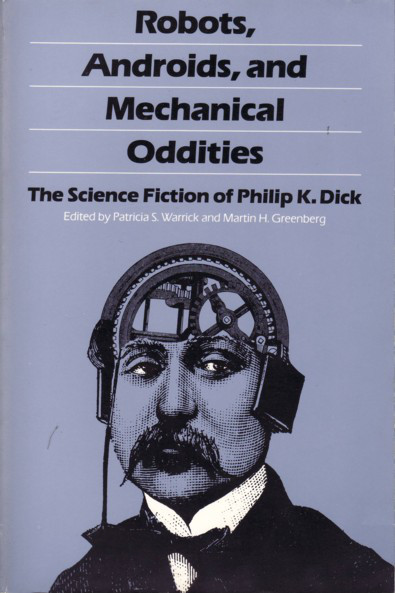

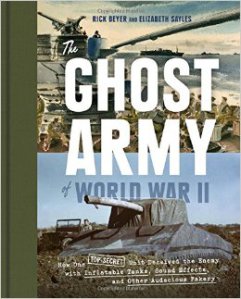

We have a fascination with war; there are a great many stories that we like to hear, of bravery in the face of defeat, in a hard-won victory. Of course, we love to hear about canny trickery. The Ghost Army by Rick Beyer and Elizabeth Sayles is one of those stories: how the 1,100 men of the 23rd used inflatable dummies, magnified sound effects, and manipulated radio messages to fool the Nazis into thinking that a fully functional unit was in place when in fact it was not. Many of the men doing this work were trained artists: their paintings, sketches, and ink drawings survive now as a testament to their labor.

We have a fascination with war; there are a great many stories that we like to hear, of bravery in the face of defeat, in a hard-won victory. Of course, we love to hear about canny trickery. The Ghost Army by Rick Beyer and Elizabeth Sayles is one of those stories: how the 1,100 men of the 23rd used inflatable dummies, magnified sound effects, and manipulated radio messages to fool the Nazis into thinking that a fully functional unit was in place when in fact it was not. Many of the men doing this work were trained artists: their paintings, sketches, and ink drawings survive now as a testament to their labor.

I read this book because it promised photos and descriptions of inflatable tanks, but kept reading because it’s so much more than that. This odd group had to pull off its deceptions well: well enough to entice enemy troops away from where they would be needed, and perhaps well enough that they would draw fire. As far as anyone can tell, they were effective in luring German forces toward them – and there were only three casualties. I doubt any other division could boast such a number.

That’s the hard part for me: the story of these soldiers in some way romanticizes the fighting. It’s certainly impossible to forget that there was real death and destruction happening elsewhere, but the part inside of us that needs comforting will always want to hear about a band of artists who shake up the opposition, Bugs Bunny style. They were good at it, and they had fun – though sometimes it meant getting two or three hours of sleep and driving long distances between assignments. But none of them had to shoot anyone they had made eye contact with. They didn’t have to fight teenagers. They understood clearly the sacrifices other people made, but they didn’t have to make all of them themselves.

That’s the hard part for me: the story of these soldiers in some way romanticizes the fighting. It’s certainly impossible to forget that there was real death and destruction happening elsewhere, but the part inside of us that needs comforting will always want to hear about a band of artists who shake up the opposition, Bugs Bunny style. They were good at it, and they had fun – though sometimes it meant getting two or three hours of sleep and driving long distances between assignments. But none of them had to shoot anyone they had made eye contact with. They didn’t have to fight teenagers. They understood clearly the sacrifices other people made, but they didn’t have to make all of them themselves.

I’m not sure if this is completely cogent – I’m still working through these thoughts like a toddler swimming through molasses – but it’s clear that the soldiers in this unit did. A chapter of the book is devoted to Christmas at Verdun in 1944; if Verdun rings a bell somewhere, it’s because it was the site of one of the horrific battles of WWI: the soldiers stayed in the old fortifications from that earlier war.

According to the book, one soldier said that the place still smelled of The Great War; another, that it was inhabited by a million ghosts. One of the more famous artists, Arthur Singer, painted a watercolor of an entrance to one of the barracks: gloomy, moldy, and crumbling away. To one side rests a skull with a German helmet still resting on its head. The painting is fuzzy, but the area around the dead man’s eyes is somehow clearer than everything else around it. Ned Harris drew a sketch of the same scene: “It brought up the whole issue that war is about life and death; and we were right in the middle of it” (159).

In the end – particularly now that the operations of the 23rd have been declassified – they served as much as translators as con men. I think that’s enough of an answer for us ditherers in the molasses.

Advertisements Share this: